(* = Phenology relates to recurring, seasonal events on land and in the heavens, many of which are often predictable based on weather, climate, temperature, latitude, time, and animal/plant physiology.)

(# = terrestrial events correspond to northern California where I reside as a Certified Wildlife Biologist Asc. and Avian Biologist.)

by Daniel Edelstein

WarblerWatch.com (Features a “Birding Tours” section that describes my 25+ years as a Birding Guide, with my guided bird watching trips for individuals and groups pursuing common and rare bird species throughout California — the majority of which occur in central and northern California (where I live in the eight-county San Francisco Bay Area.)

(My 17-year-old wood-warbler blog that features articles and photo quizzes.)

danielsmerrittclasses.blogspot.com

(my above blog # highlights adult bird-related classes I began teaching periodically in 2003 at Merritt College in Oakland, California)

January, 2024

Sky Watch: (Courtest of earthsky.org)

Moon & Planet Rise & Set Times (Pacific Time)

(courtesy of https://www.timeanddate.com/astronomy/night/)

At the above link, type in your town/city to learn your area’s Moon & Planet Rise & Set Times.

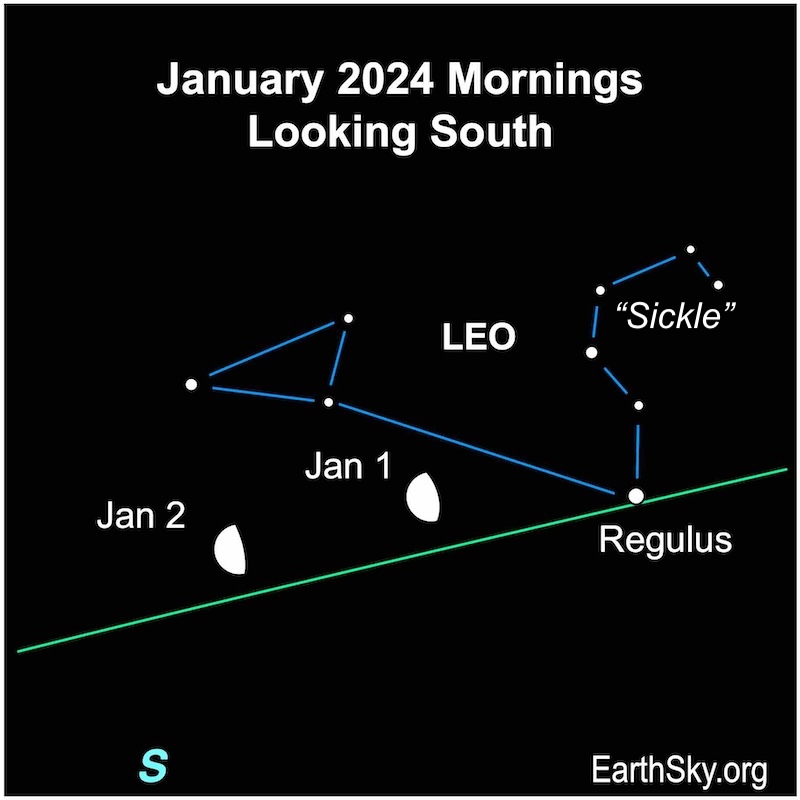

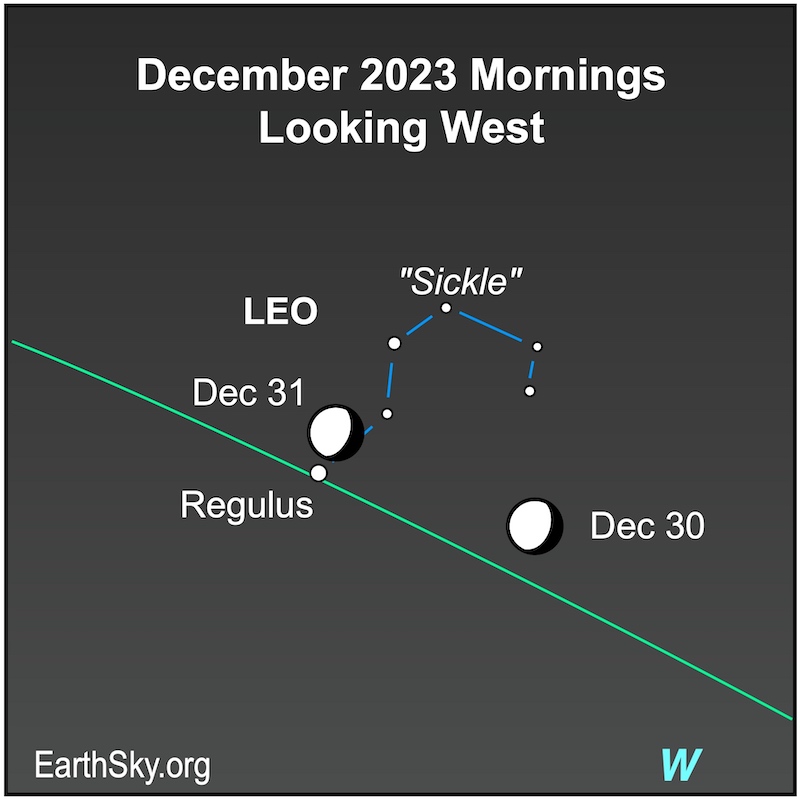

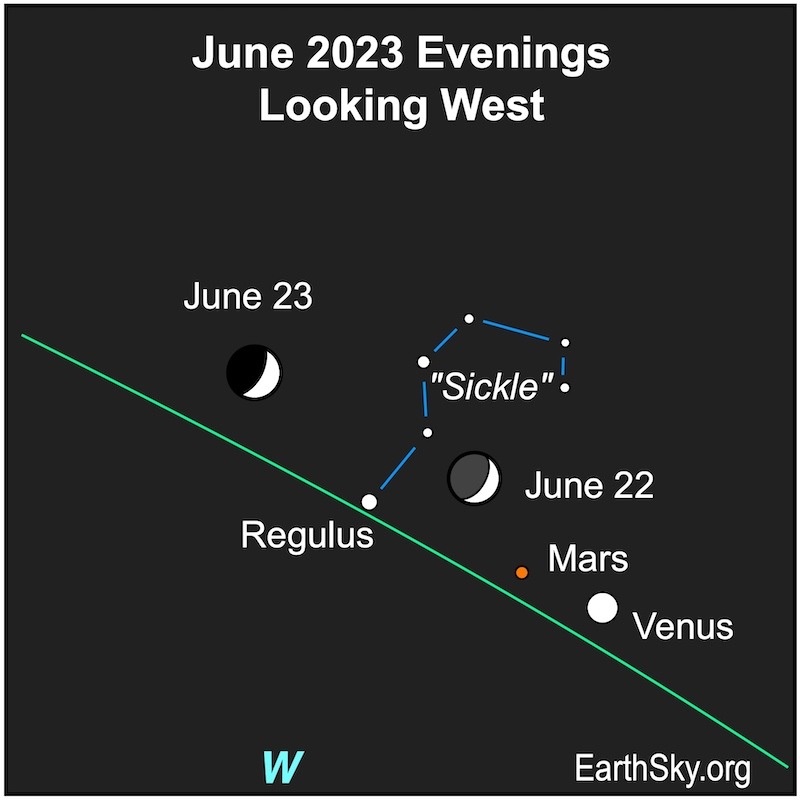

January 1 and 2 mornings: Moon near Regulus and the Sickle

On the mornings of January 1 and 2, 2024, the waning gibbous moon will lie near Regulus, the bright star marking the bottom of the backward question mark asterism called the Sickle. Regulus is the brightest star in Leo the Lion. They’ll rise late the night before and be high in the morning sky.

EarthSky Minute: January 1-4

Join EarthSky’s Marcy Curran for a 1-minute video preview of the best sky events for January 1-4.

Moon at apogee January 1

The moon will reach apogee – its farthest distance from Earth in its elliptical orbitaround Earth – at 15 UTC (10 a.m. CST) on January 1, 2024, when it’s 251,598 miles (404,909 kilometers) away.

January 2-3: Earth closest to the sun

For 2024, the Earth’s closest point to the sun is called perihelion. It comes at 1 UTCon January 3 (8 p.m. CST on January 2).

EarthSky Minute: January moon phases

Join EarthSky’s Marcy Curran for a 1-minute video preview preview of the moon phases – and dates when the moon visits planets – for the month of January.

January 3-4: Last quarter moon

The instant of last quarter moon will fall at 3:30 UTC on January 4, 2024 (10:30 p.m. CST January 3). It’ll rise around midnight your local time and will set around noon.

January 4 morning: Quadrantid meteor shower

The predicted peak of the Quadrantid meteor shower is on the early morning of January 4, 2024. A bright last quarter moon will rise around midnight and shine the rest of the night. Try observing late night January 3 to dawn January 4, in moonlight.

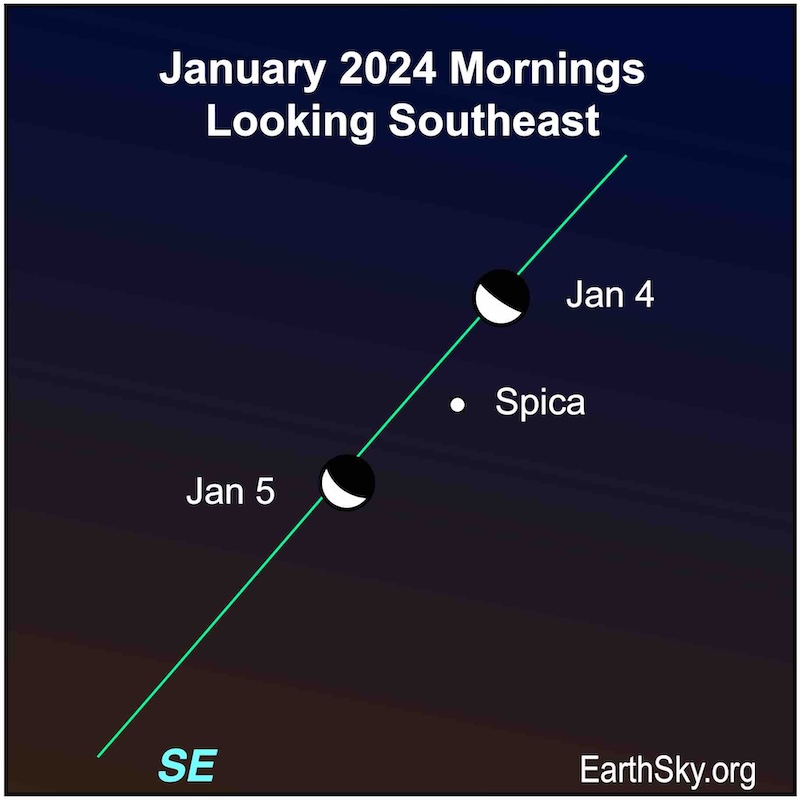

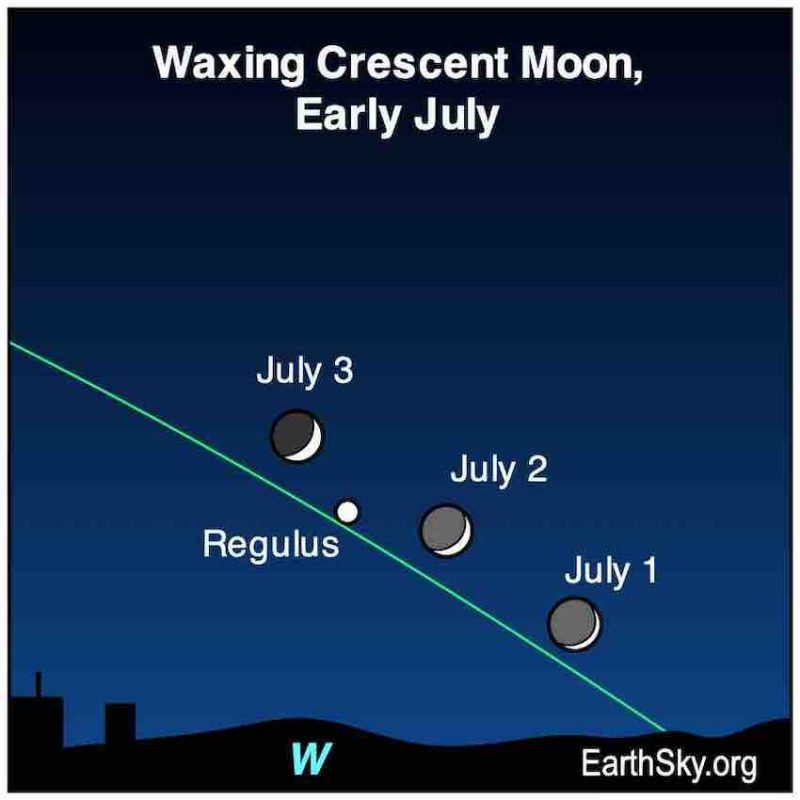

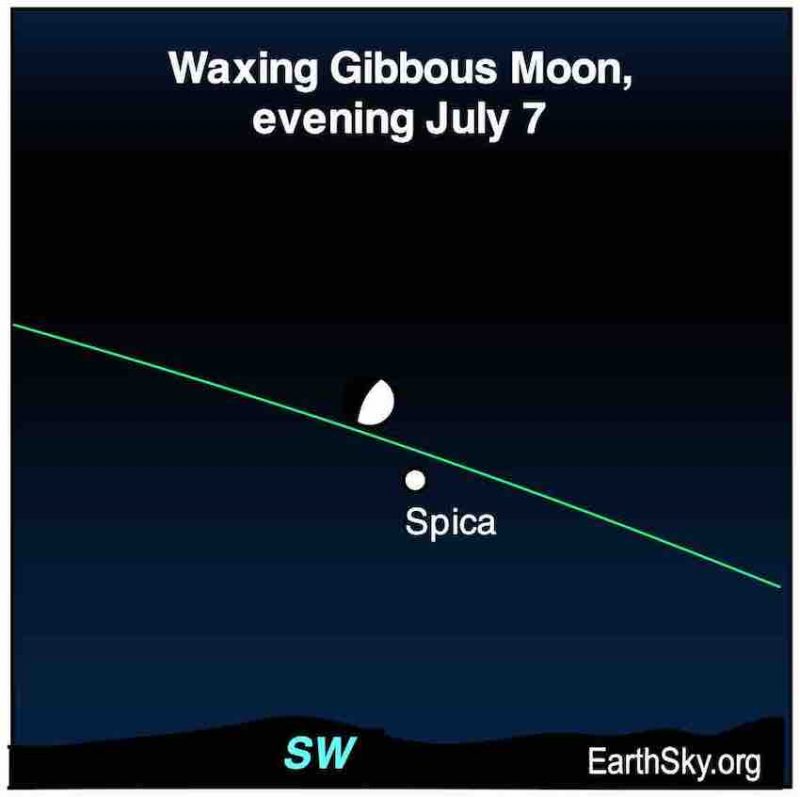

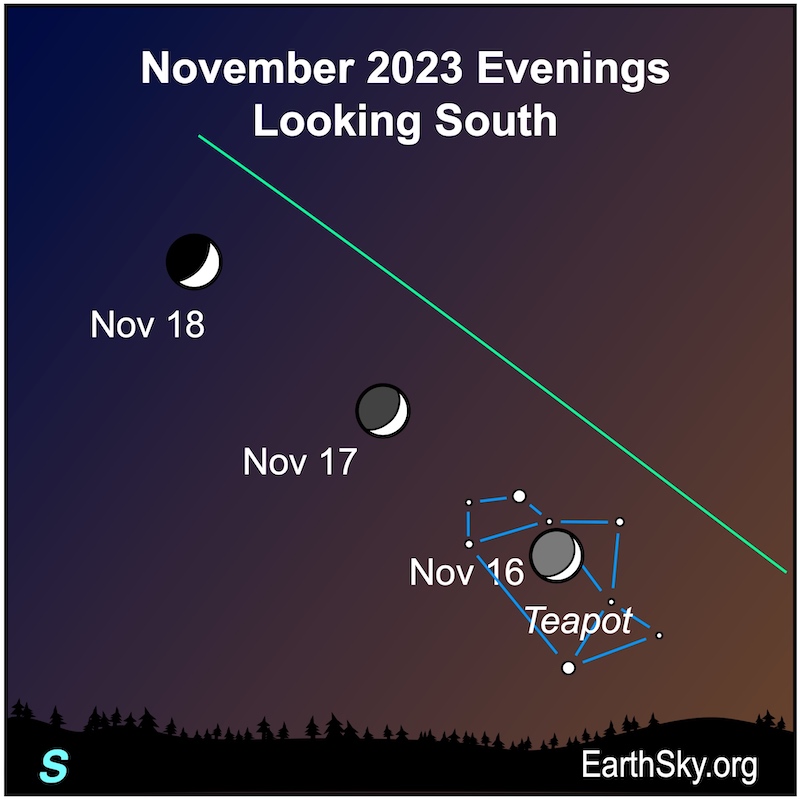

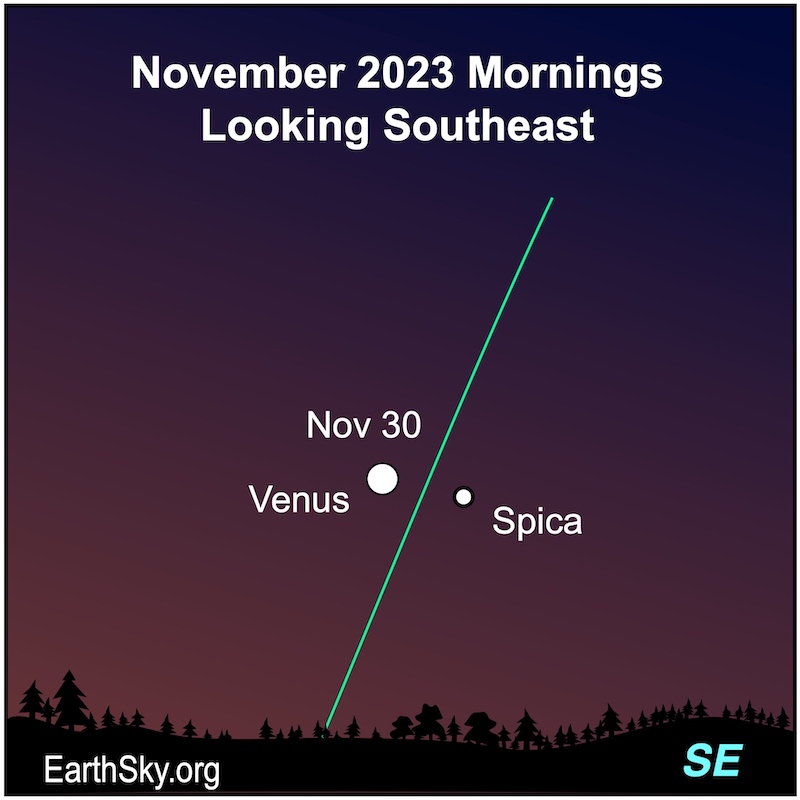

January 4 and 5 mornings: Moon near Spica

On the morning of January 4 and 5, 2024, the waning crescent moon will hang near the bright star Spica. Spica is the brightest star of Virgo the Maiden.

Our charts are mostly set for the northern half of Earth. To see a precise view – and time – from your location, try Stellarium Online.

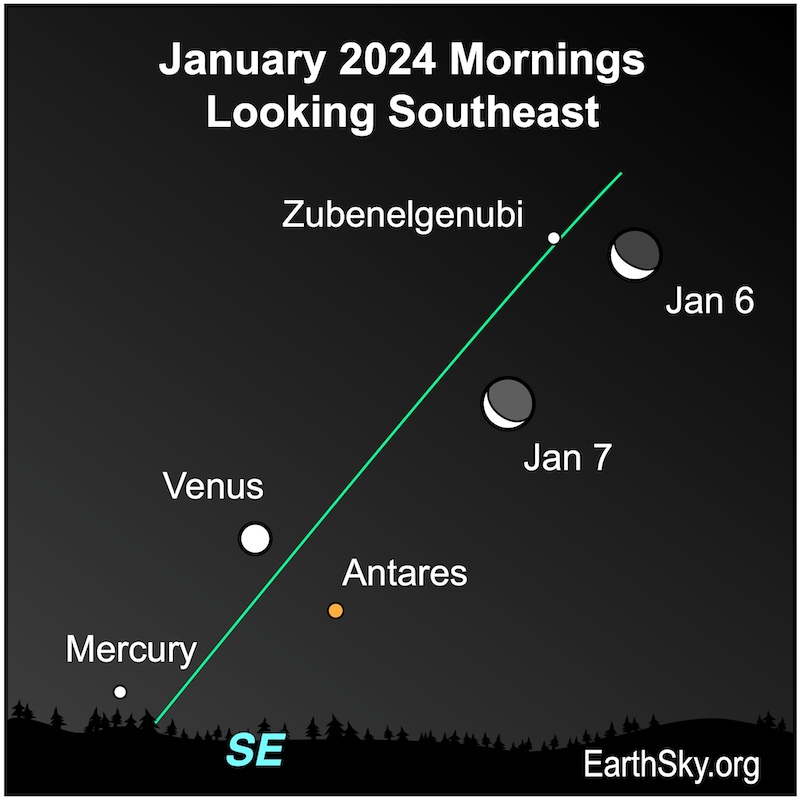

January 6 and 7 mornings: Moon near Zubenelgenubi

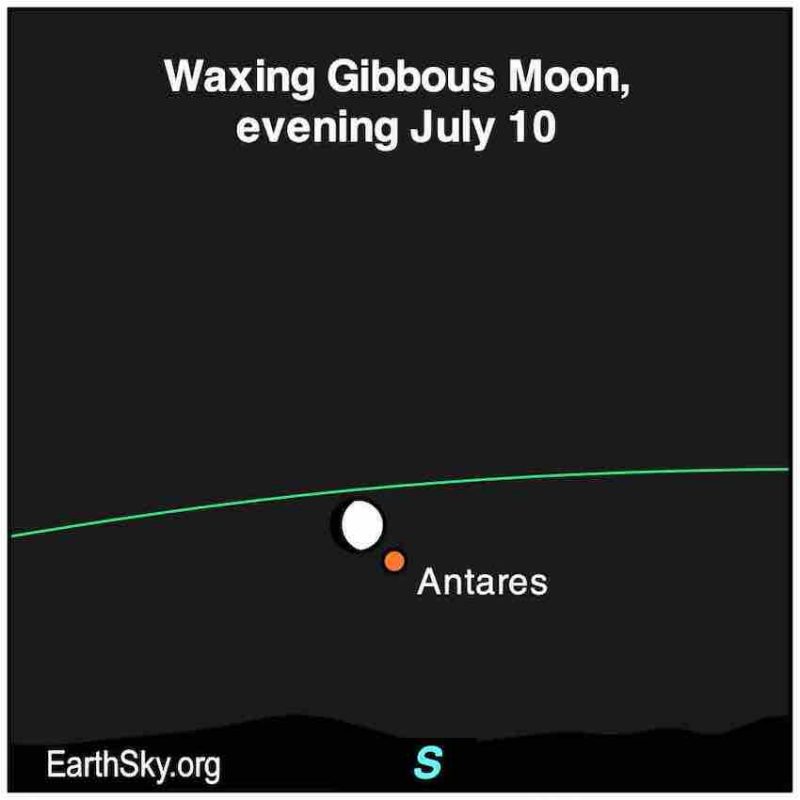

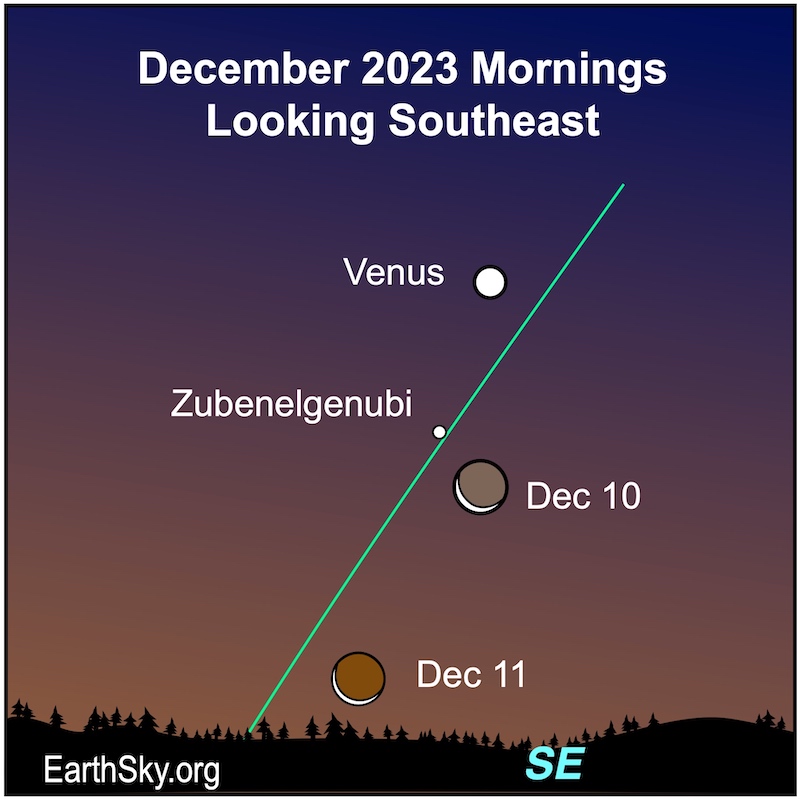

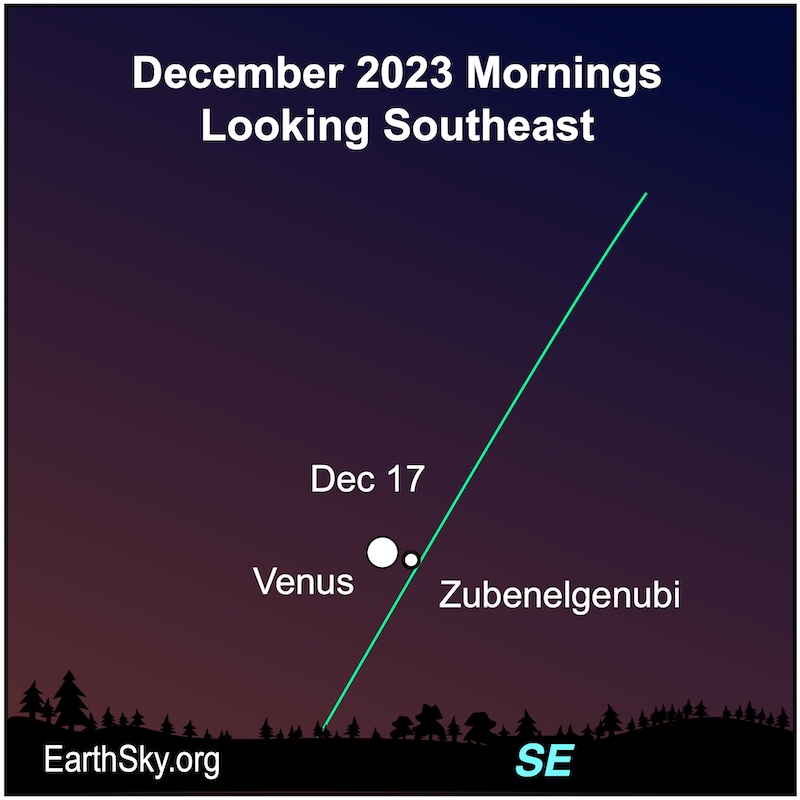

On the mornings of January 6 and 7, 2024, the waning crescent moon slides past a star with a strange sounding name: Zubenelgenubi. Zubenelgenubi means “Southern Claw” in Arabic. Many people used to consider this star as part of Scorpius the Scorpion. But today it’s part of Libra the Scales. Nearby are the planets Venus and Mercury and the bright star Antares.

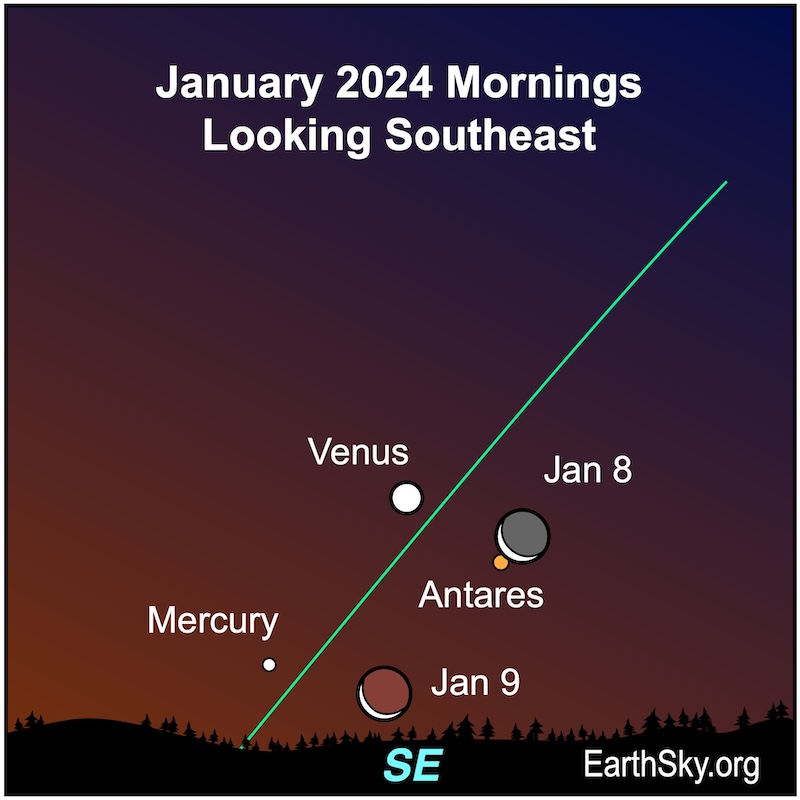

January 8 and 9 mornings: Moon near Venus, Mercury and Antares

On the morning of January 8, the thin waning crescent moon will lie next to the bright star Antares in Scorpius the Scorpion. Skywatchers in most of North America and part of South America will see the moon pass in front of – or occult – Antares. However, this event will occur in daylight. That morning, bright Venus will shine nearby. On the following morning, January 9, a thinner crescent moon will lie close to the horizon with Mercury nearby. Can you see a delicate glow on the unlit portion of the crescent moon? That’s earthshine! It’s reflected light from the Earth.

January 11: New moon

The instant of new moon will fall at 11:57 UTC (6:57 a.m. CST) on January 11, 2024. It’s a perfect time for stargazing under dark skies. The new moon rises and sets with the sun.

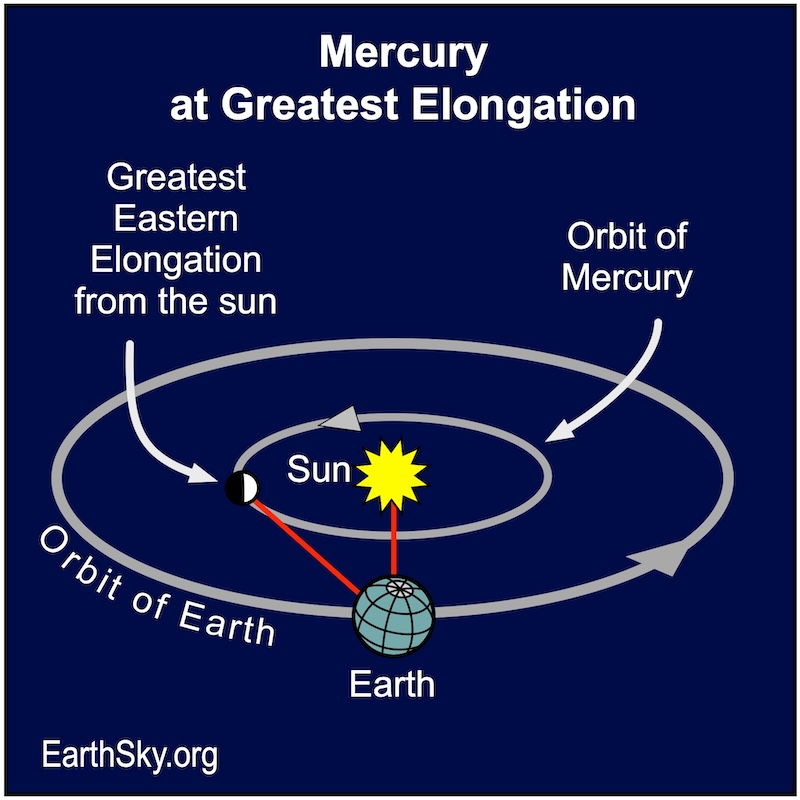

January 12: Mercury at greatest elongation

Mercury reaches greatest elongation – distance from the sun – in the morning sky at 15 UTC January 12, 2023.

Our charts are mostly set for the northern half of Earth. To see a precise view – and time – from your location, try Stellarium Online.

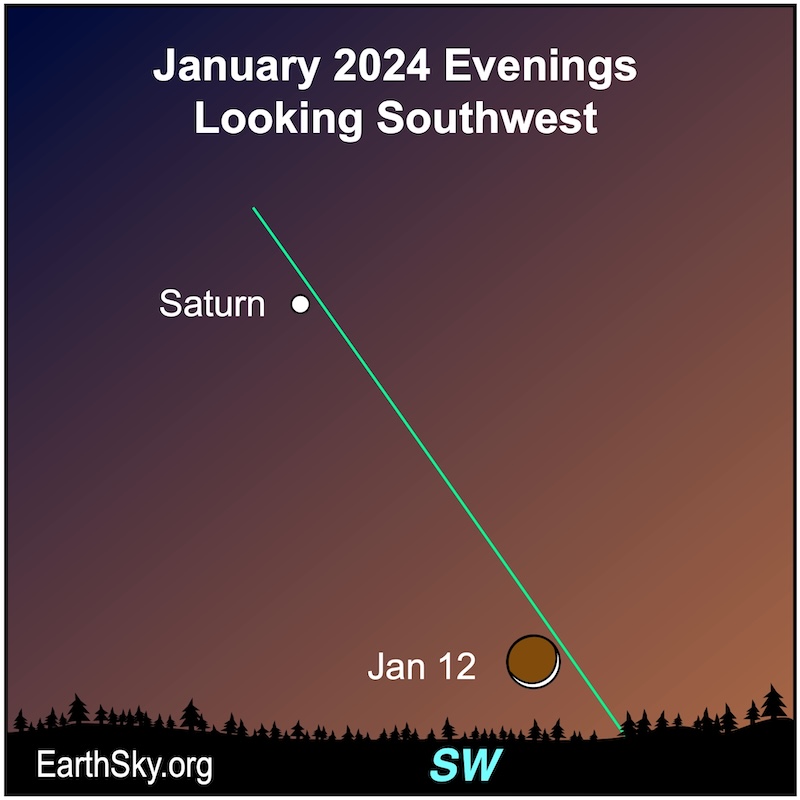

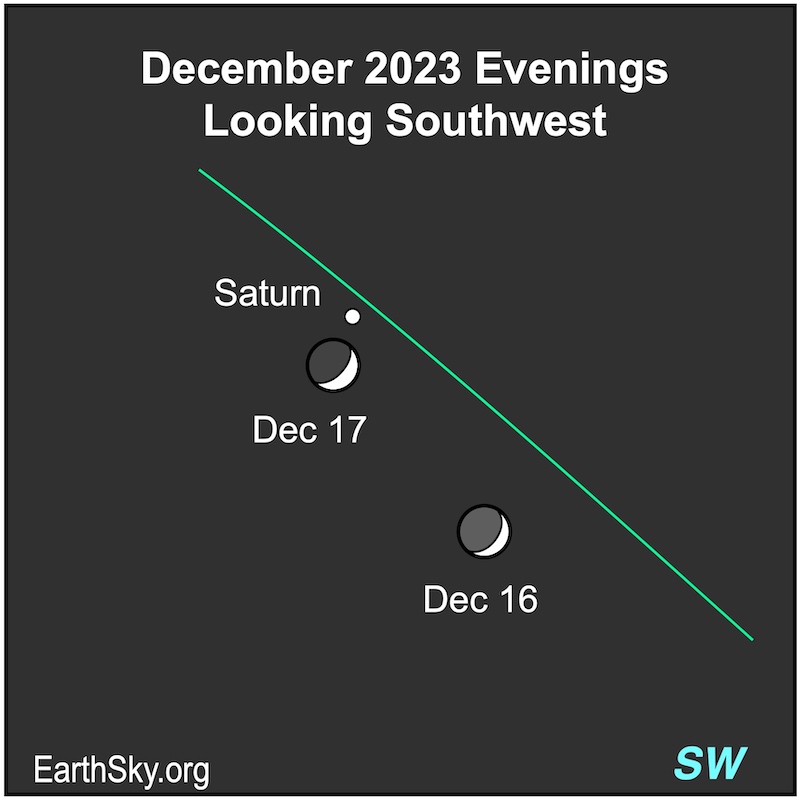

January 12 evening: Slender crescent moon near Saturn

Viewers with a low southwestern horizon and clear skies will spot the very thin waxing crescent moon in bright twilight shortly after sunset on January 12, 2024. Saturn will be the steady golden light higher in the sky. Check out the unlit portion of the moon. That lovely glow you see is earthshine, which is light reflected from Earth.

January 13: Moon reaches perigee

The moon will reach perigee – its closest point in its elliptical orbit around Earth – at 11 UTC (6 a.m. CST) on January 13, 2024, when it’s 225,102 miles (362,267 kilometers) away.

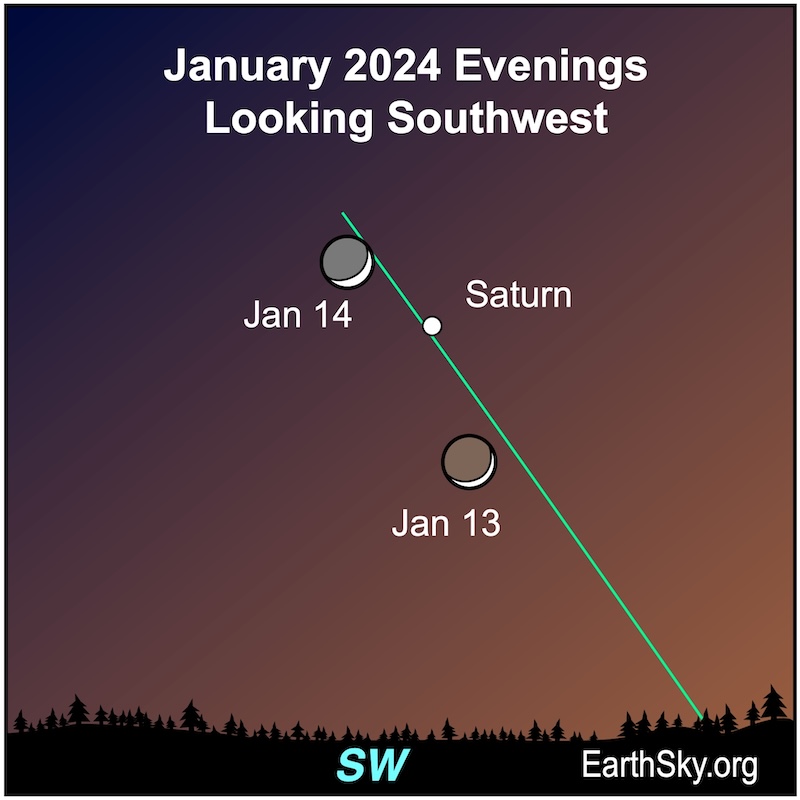

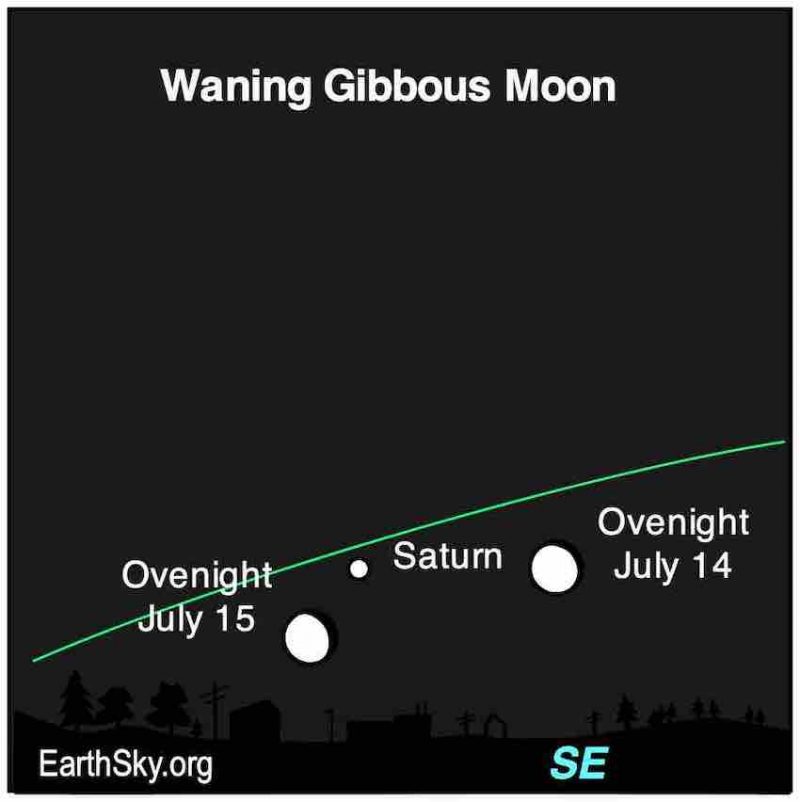

January 13 and 14 evenings: Moon near Saturn

Early on the evenings of January 13 and 14, 2024, the thin waxing crescent moon will pass Saturn. Also, look for earthshine, a glow on the unlit side of the moon. It’s reflected light from the Earth.

Our charts are mostly set for the northern half of Earth. To see a precise view – and time – from your location, try Stellarium Online.

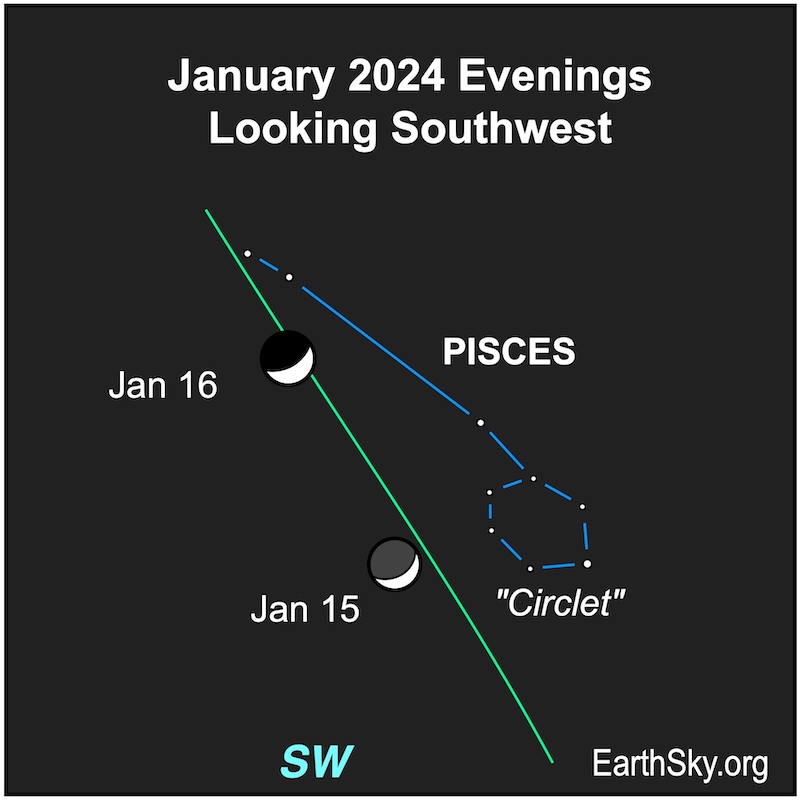

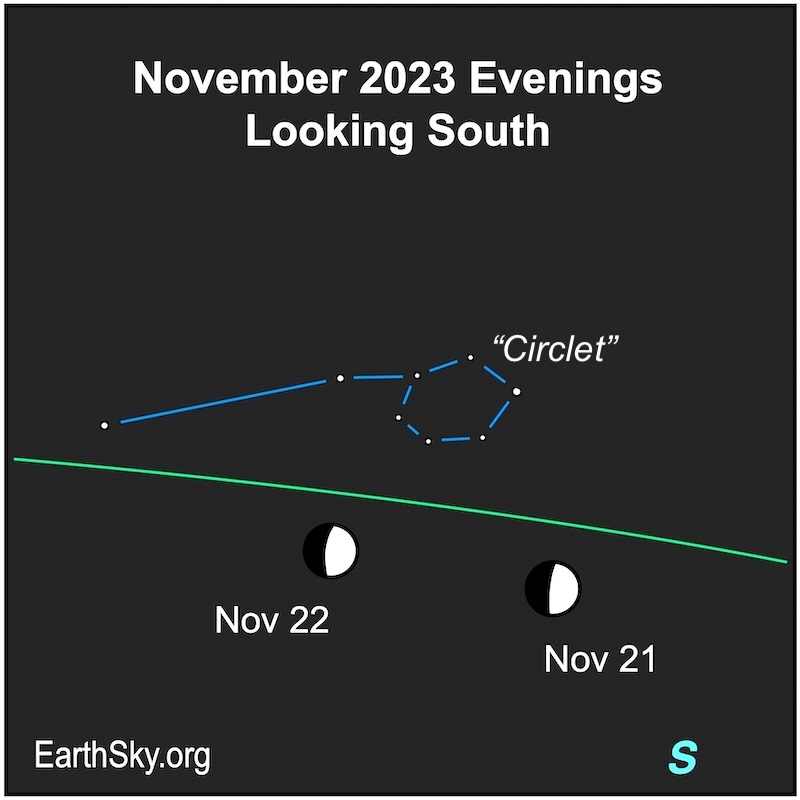

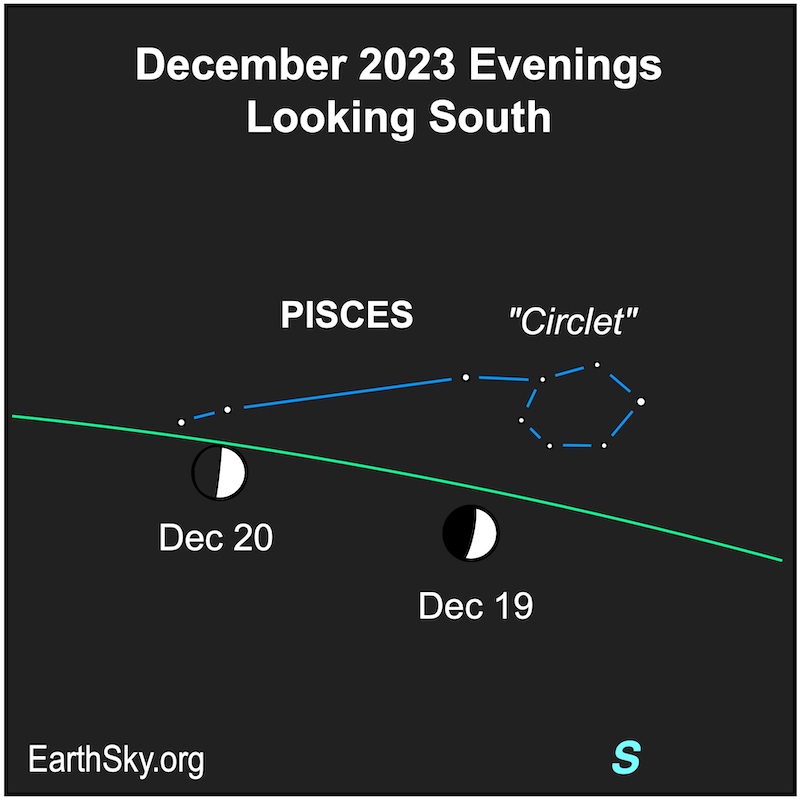

January 15 and 16 evenings: Moon near the Circlet

The growing waxing crescent moon will pass the faint but distinct Circlet asterism in Pisces the Fish on the evenings of January 15 and 16, 2024. The moon and the Circlet will be visible after darkness falls and will set before midnight.

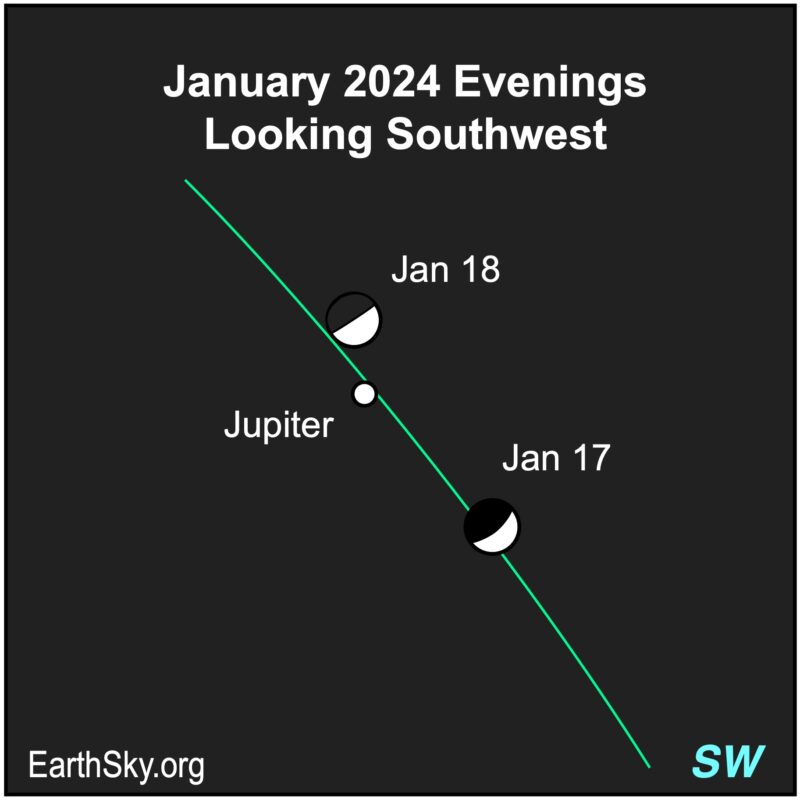

January 18: 1st quarter moon

The instant of 1st quarter moon will fall at 3:53 UTC (10:53 p.m. CST on January 17), on January 18, 2024. The 1st quarter moon rises around noon your local time and sets around midnight.

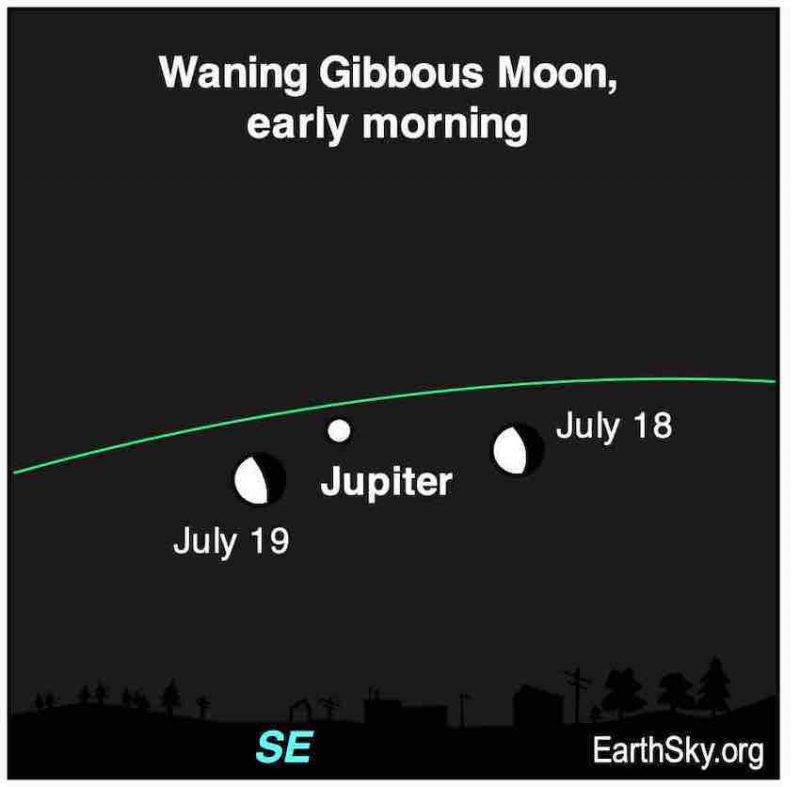

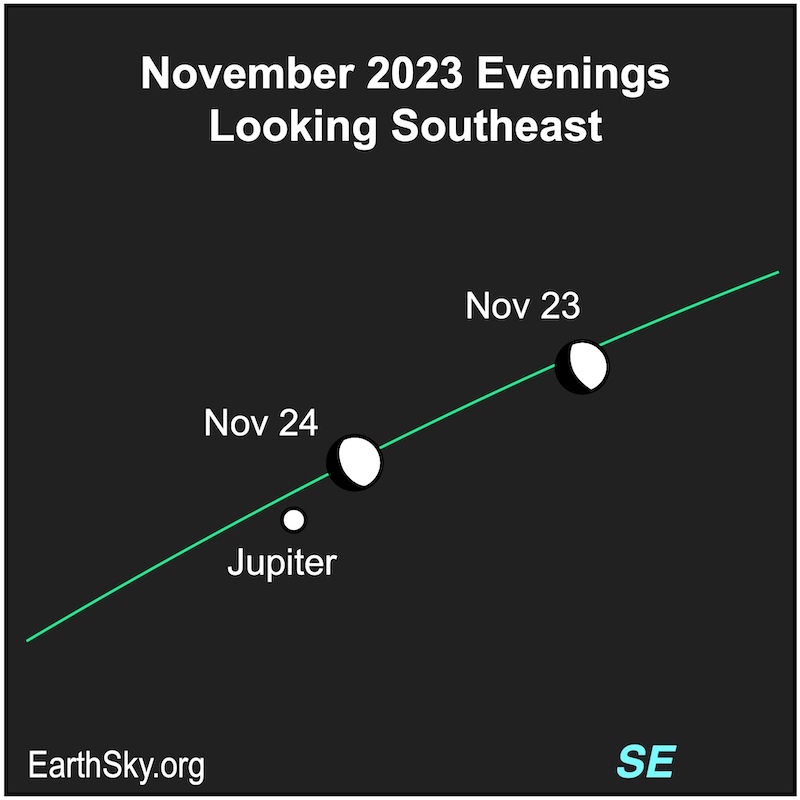

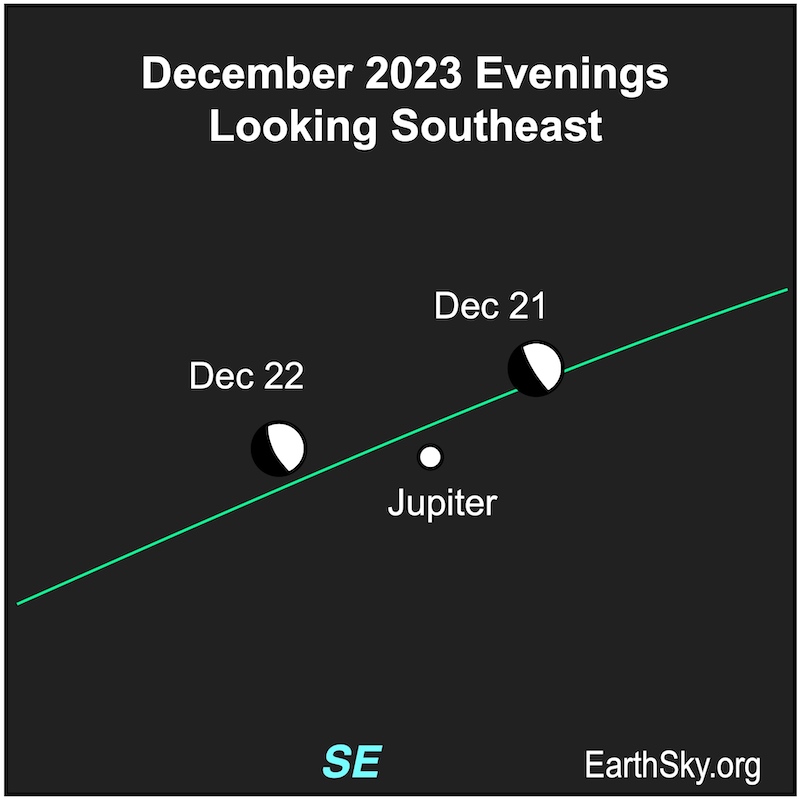

January 17 and 18 evenings: Moon near Jupiter

On the evenings of January 17 and 18, 2024, the 1st quarter moon will glow near the bright planet Jupiter. The moon and Jupiter will set around midnight.

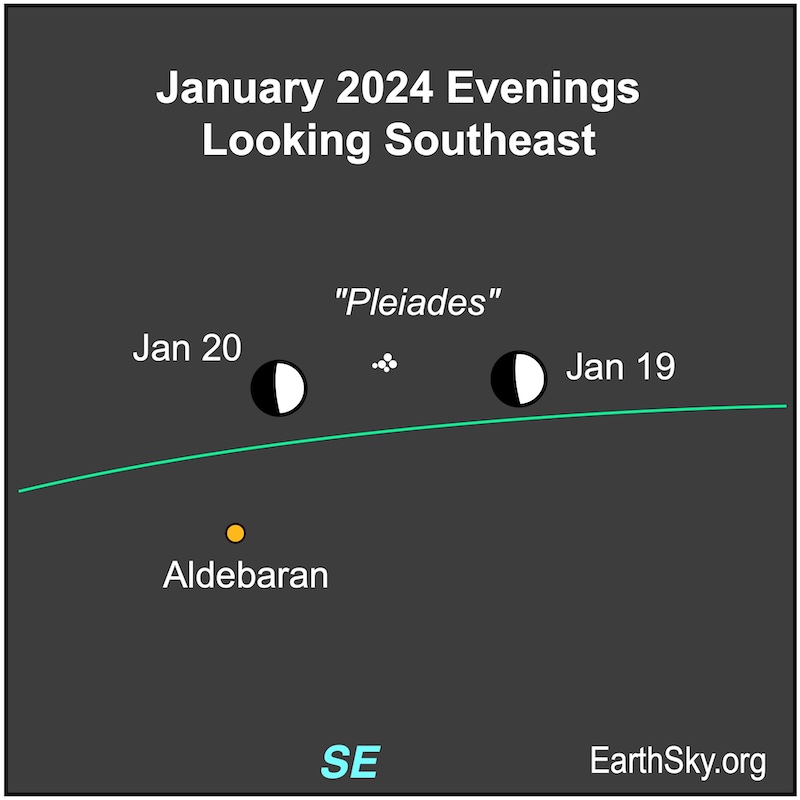

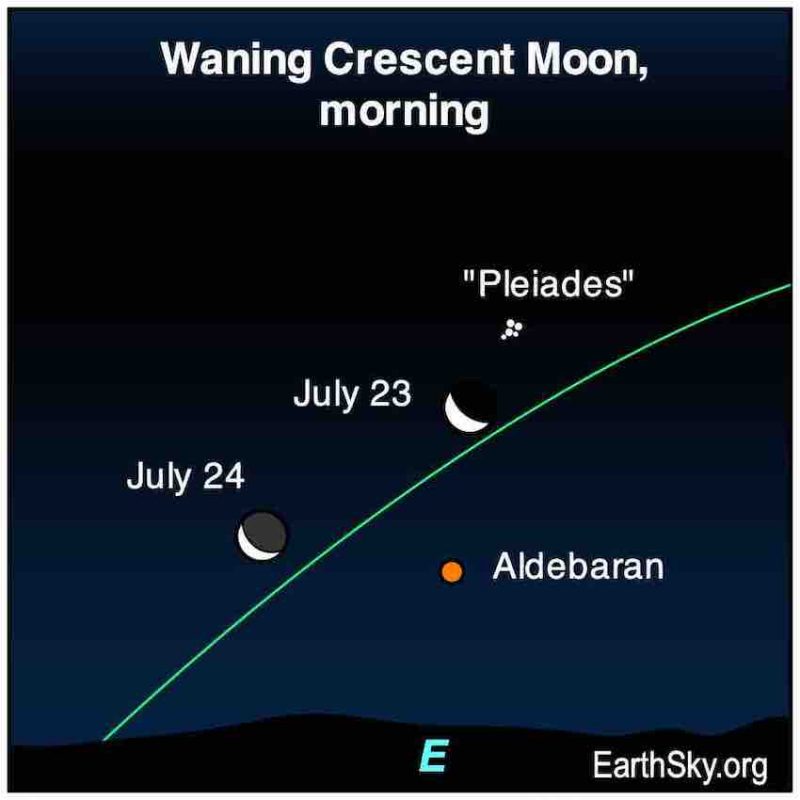

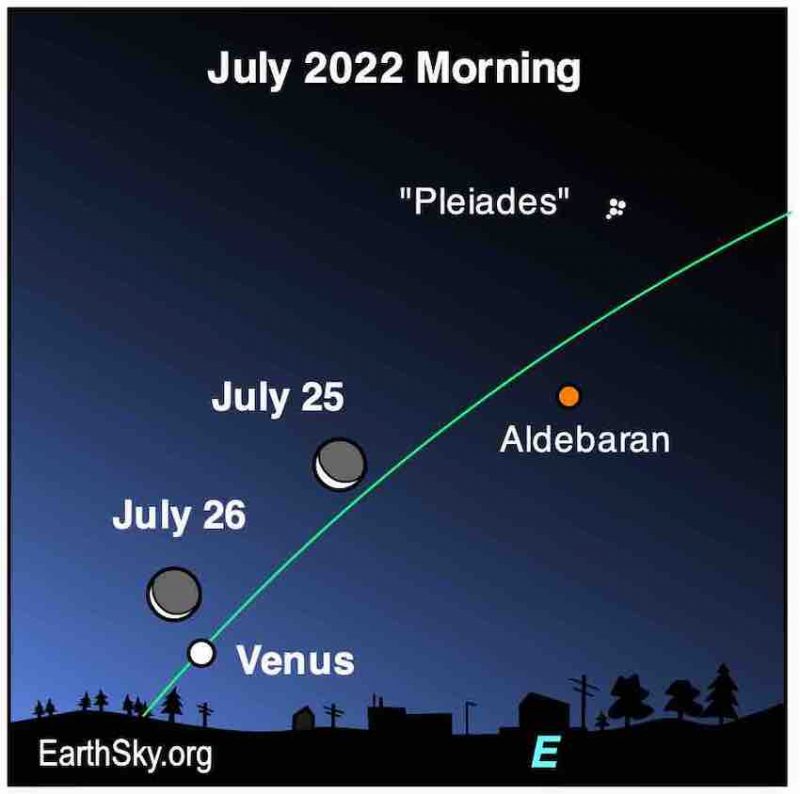

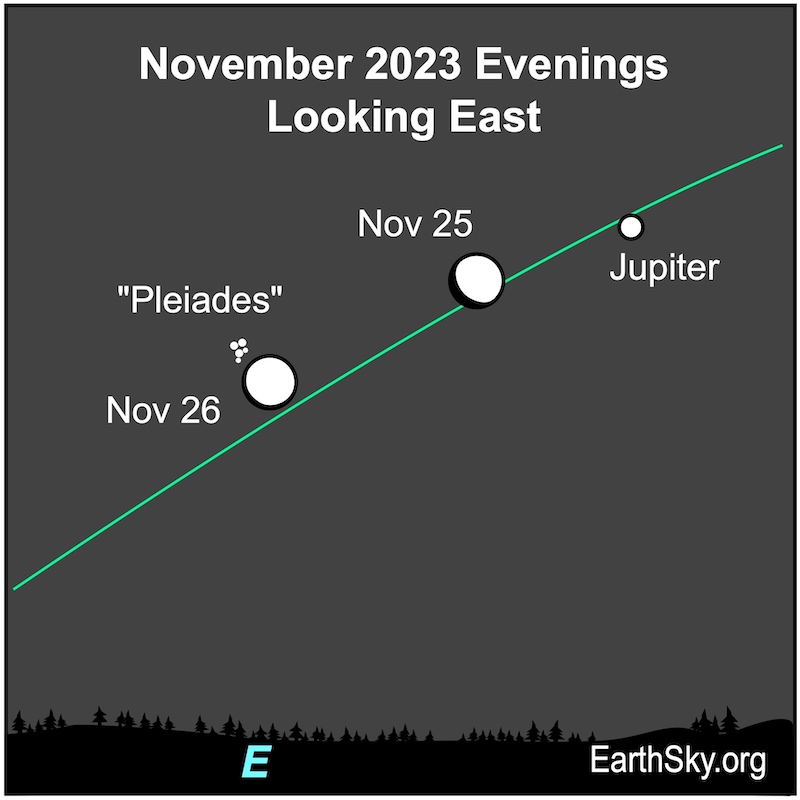

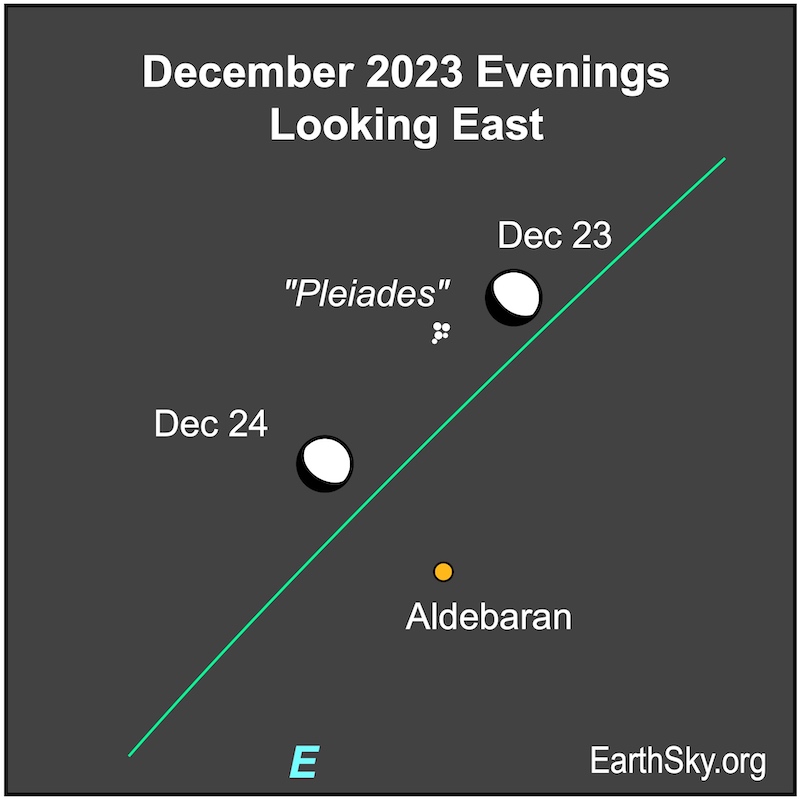

January 19 and 20 evenings: Moon near Aldebaran and the Pleiades

The bright waxing gibbous moon will pass the Pleiades star cluster on the evenings of January 19 and 20, 2024. The Pleiades is also known as the Seven Sisters or Messier 45 and appears as a glittering, bluish cluster of stars in the constellation Taurus the Bull. It’ll also be near the fiery orange star Aldebaran. The moon and Pleiades will cross the sky together and set after midnight.

Our charts are mostly set for the northern half of Earth. To see a precise view – and time – from your location, try Stellarium Online.

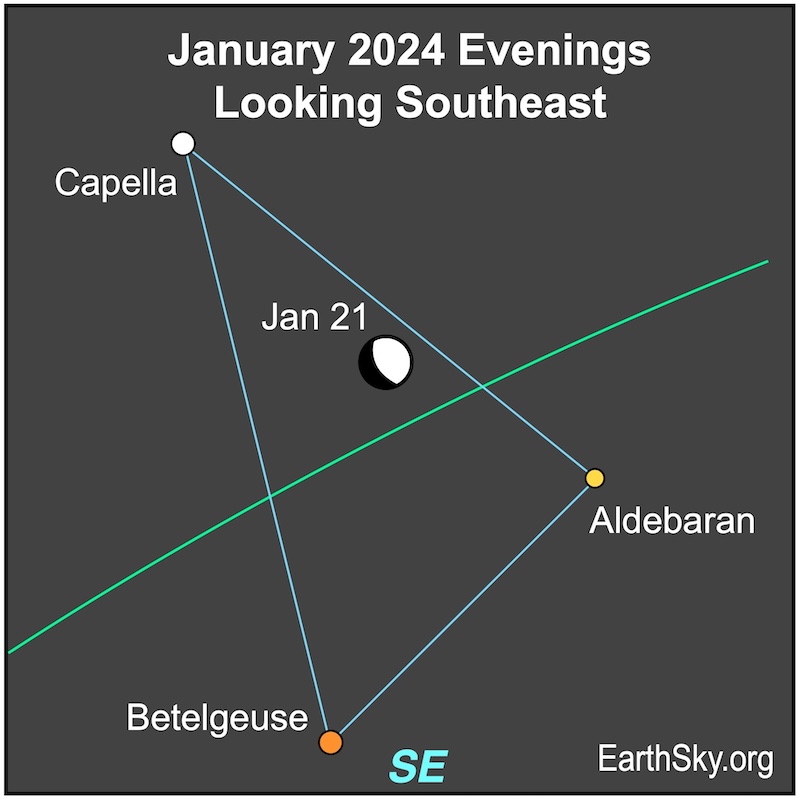

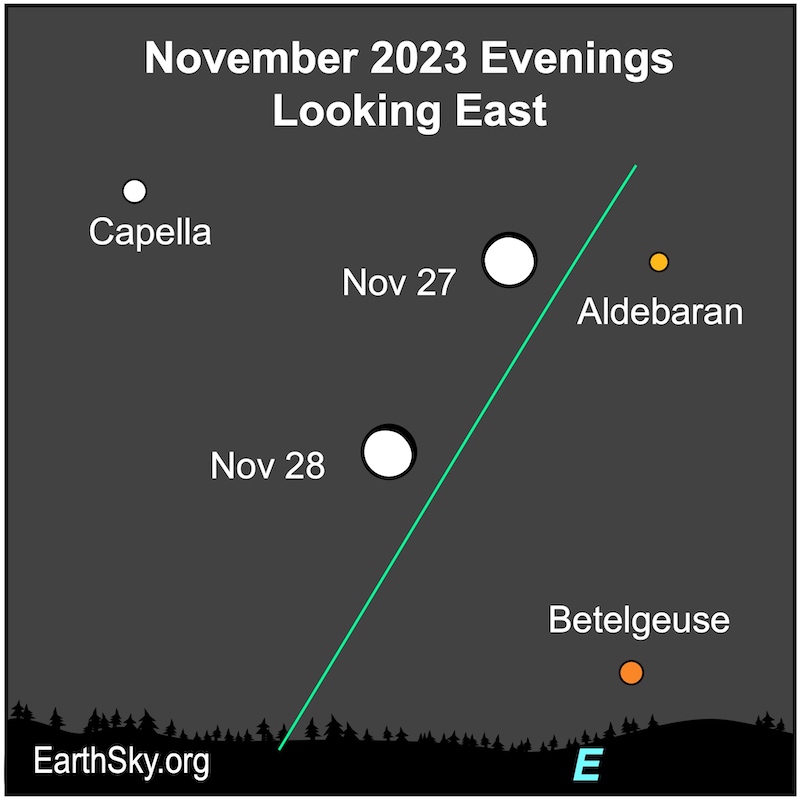

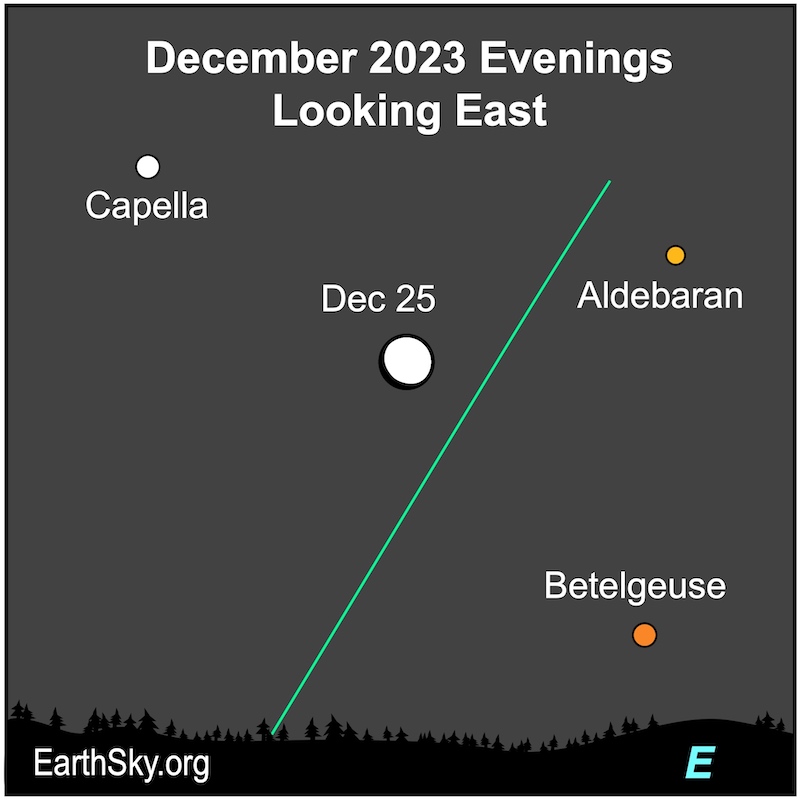

January 21 evening: Moon near Capella, Aldebaran and Betelgeuse

On January 21, 2024, the bright waxing gibbous moon will lie within a triangle formed by three bright stars. It’ll be near the fiery orange star Aldebaran of Taurusthe Bull and Orion’s mighty red supergiant star Betelgeuse. The bright, golden star is Capella of the constellation Auriga the Charioteer. If you catch Capella low on the horizon, it may be flashing like a small disco ball. You can follow them all night until about an hour before dawn.

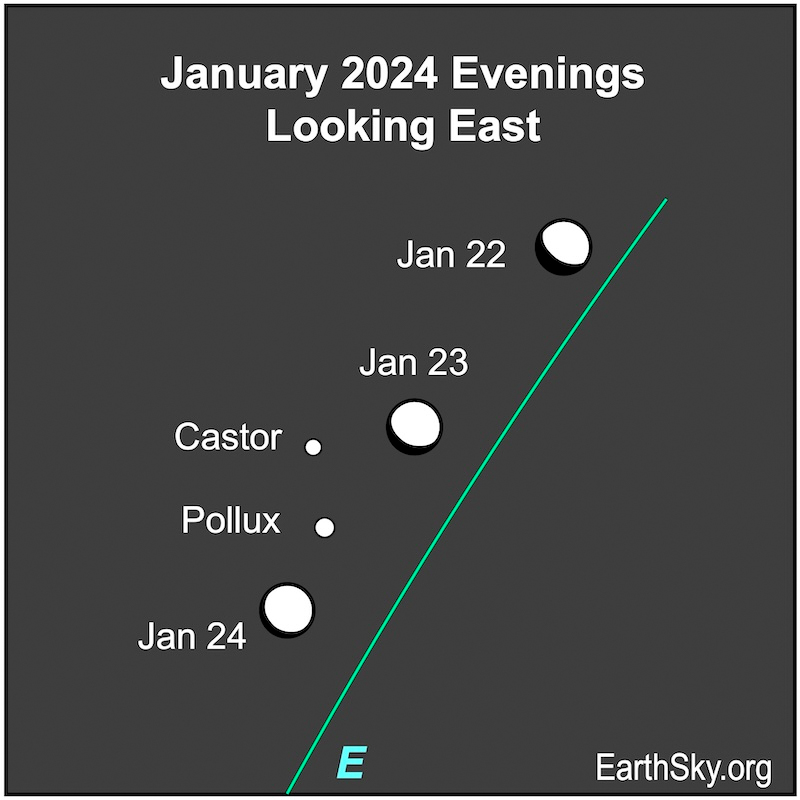

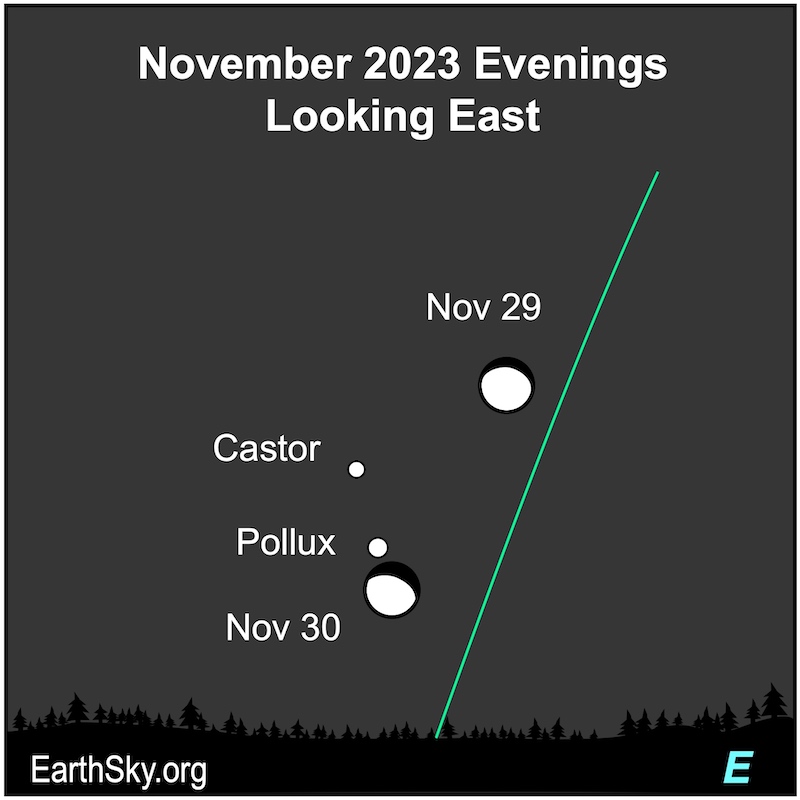

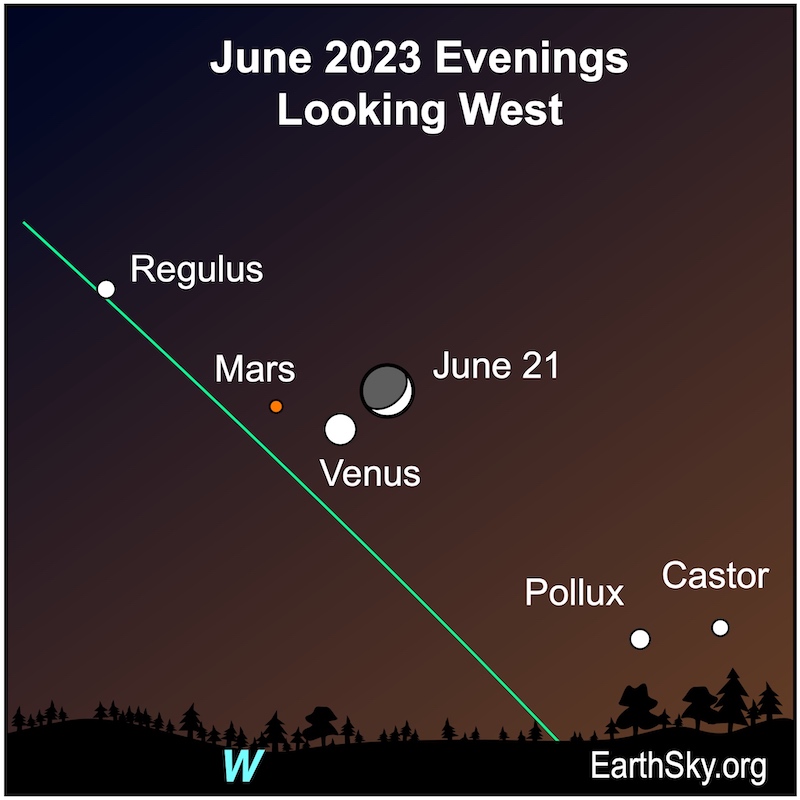

January 22, 23, and 24 evenings: Moon near Castor and Pollux

On the evenings of January 22, 23, and 24, 2024, the bright waxing gibbous moon will pass Castor and Pollux, the twin stars of Gemini. They’ll rise a few hours after sunset and travel across the sky’s dome until a little before sunrise.

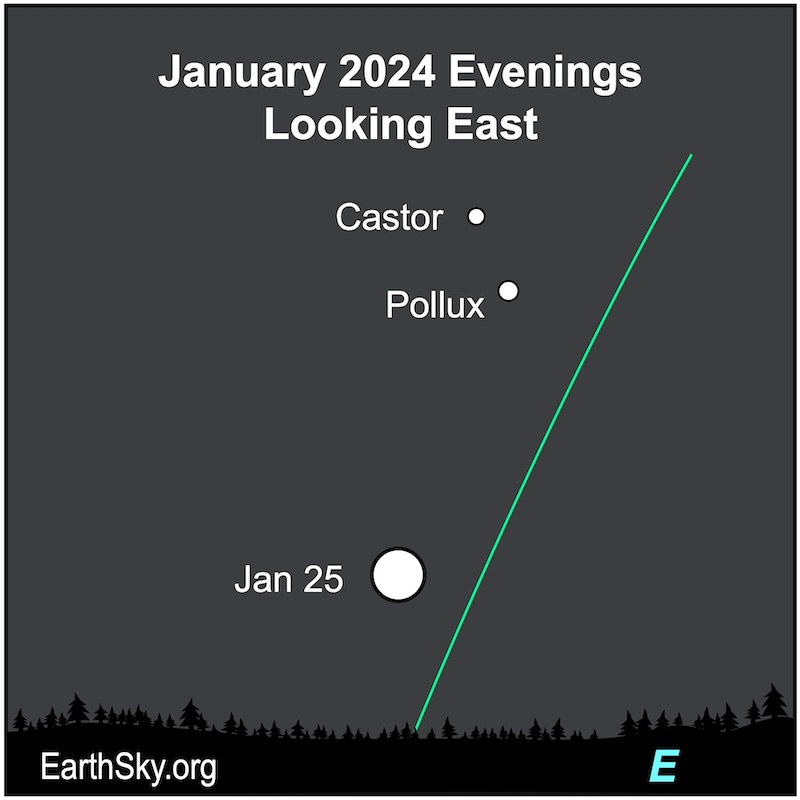

January 25, all night: Full Wolf Moon

The instant of full moon – the Wolf Moon – will fall at 17:54 UTC on January 25, 2024 (12:54 p.m. CST). It will be near the twin stars Castor and Pollux, of Gemini the Twins.

Our charts are mostly set for the northern half of Earth. To see a precise view – and time – from your location, try Stellarium Online.

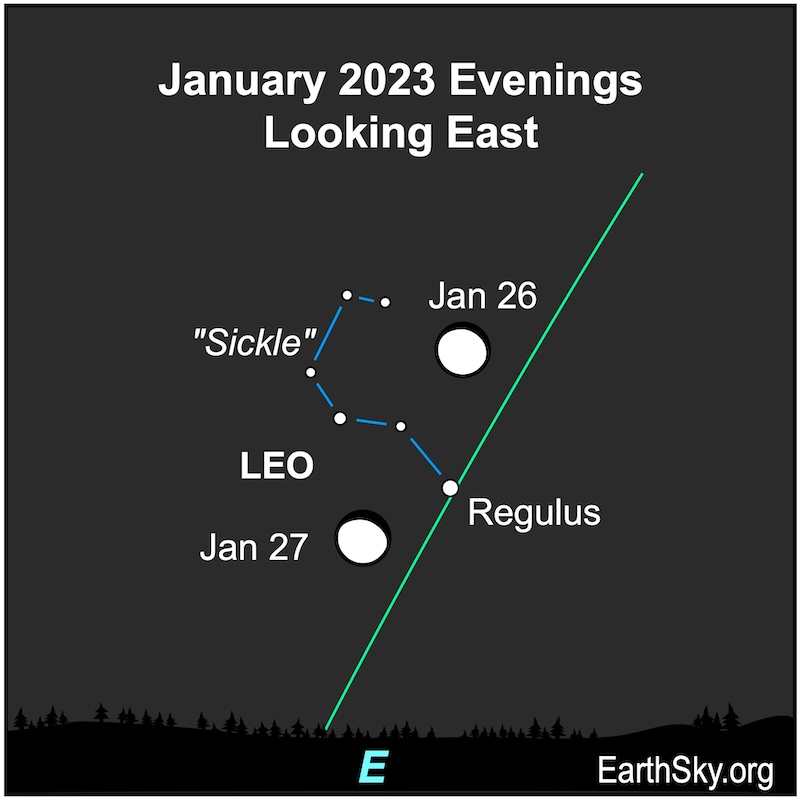

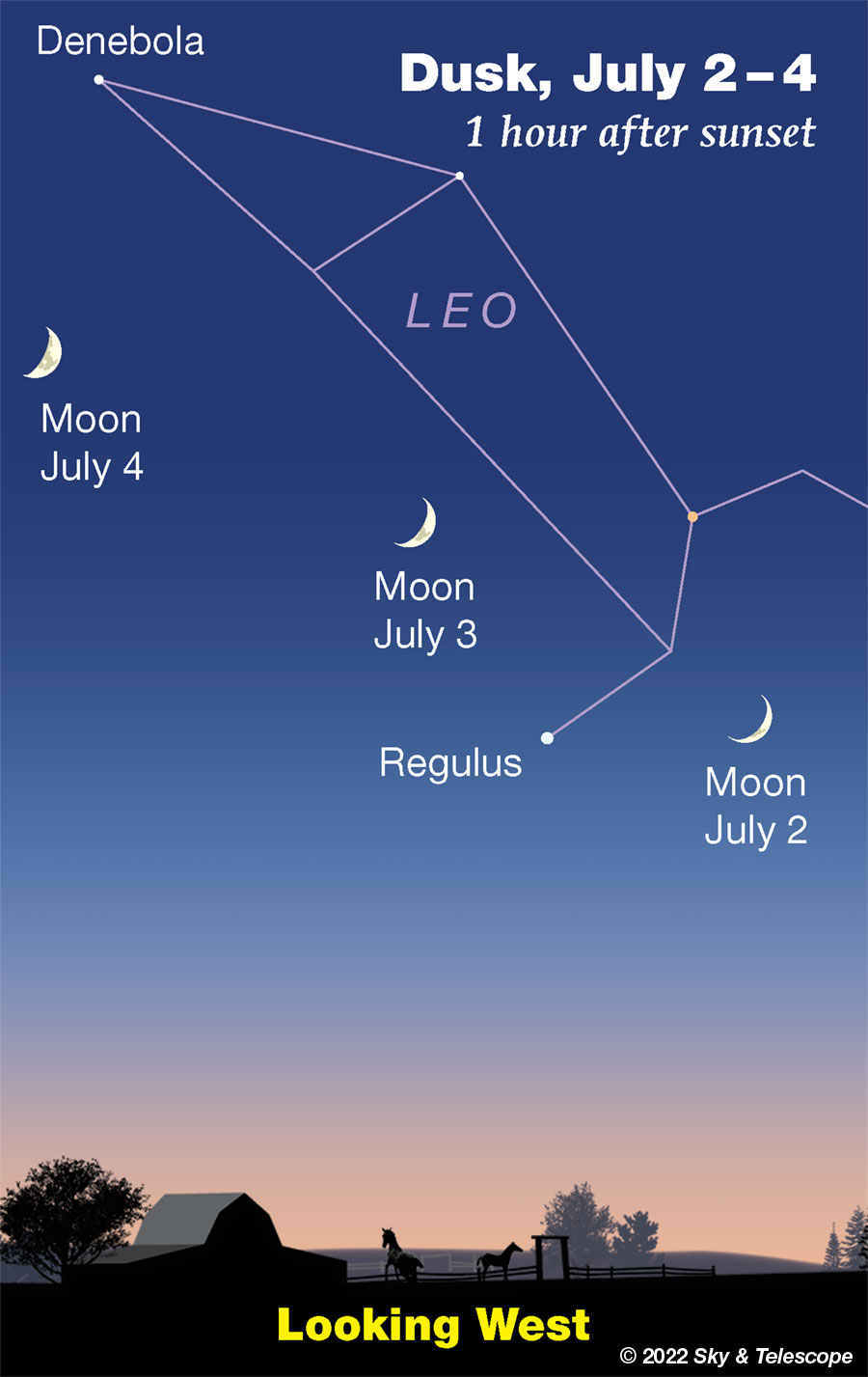

January 26 and 27 evenings: Moon near the Sickle

On the evenings of January 26 and 27, 2024, the waning gibbous moon will float near Regulus, marking the bottom of the backward question mark asterism called the Sickle. Regulus is the brightest star in Leo the Lion. They’ll be visible most of the night.

Moon at apogee January 29

The moon will reach apogee – its farthest distance from Earth in its elliptical orbitaround the Earth – at 8 UTC (3 a.m. CST) on January 29, 2024, when it’s 252,138 miles (405,777 kilometers) away.

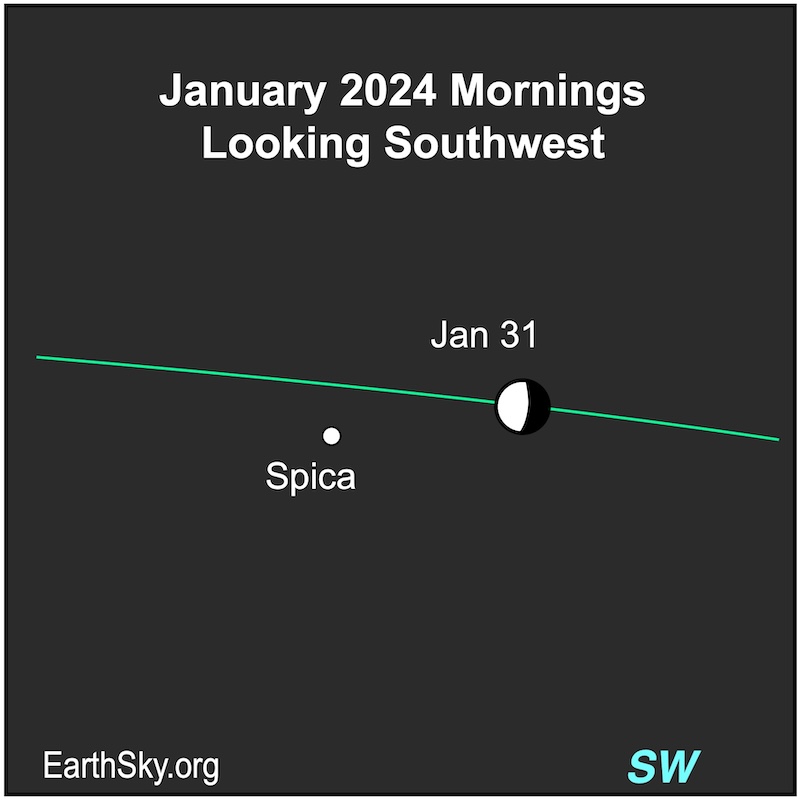

January 31 morning: Moon near Spica

On the final morning of January, the waning gibbous moon will hang near the bright star Spica in Virgo the Maiden.

Our charts are mostly set for the northern half of Earth. To see a precise view – and time – from your location, try Stellarium Online.

Planets in January 2024

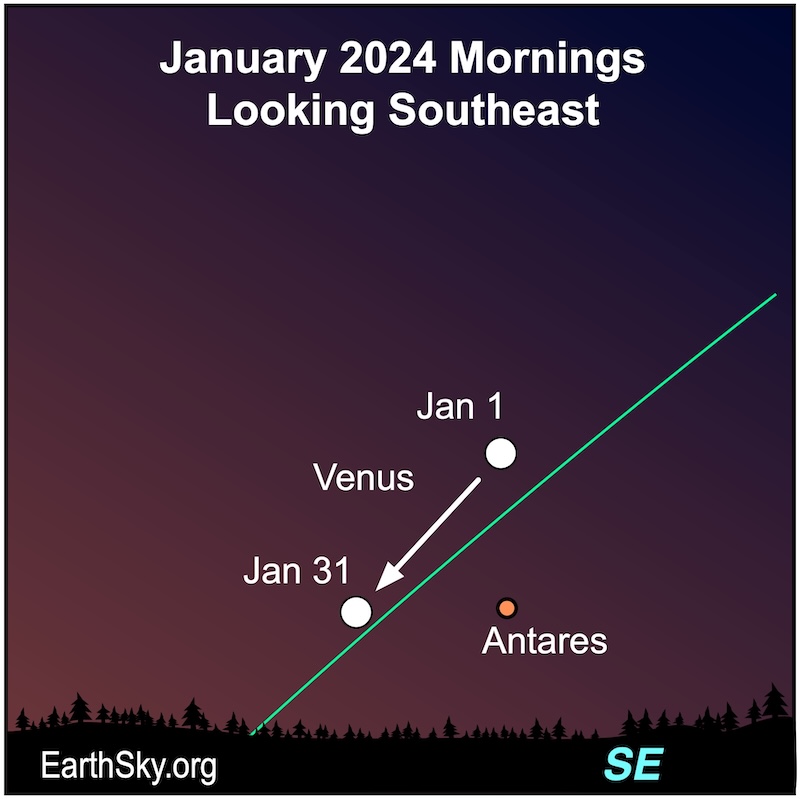

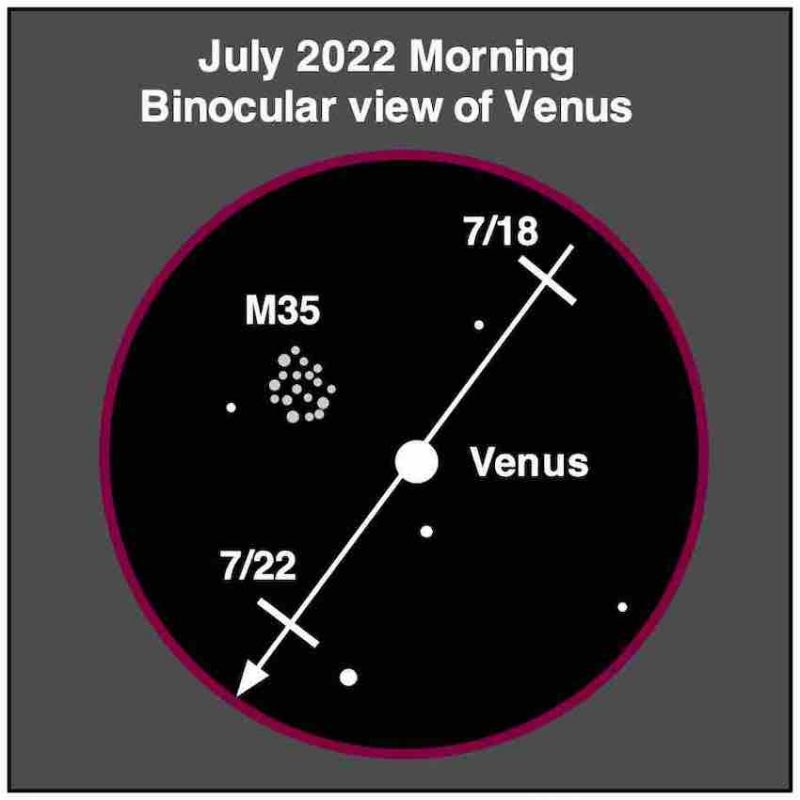

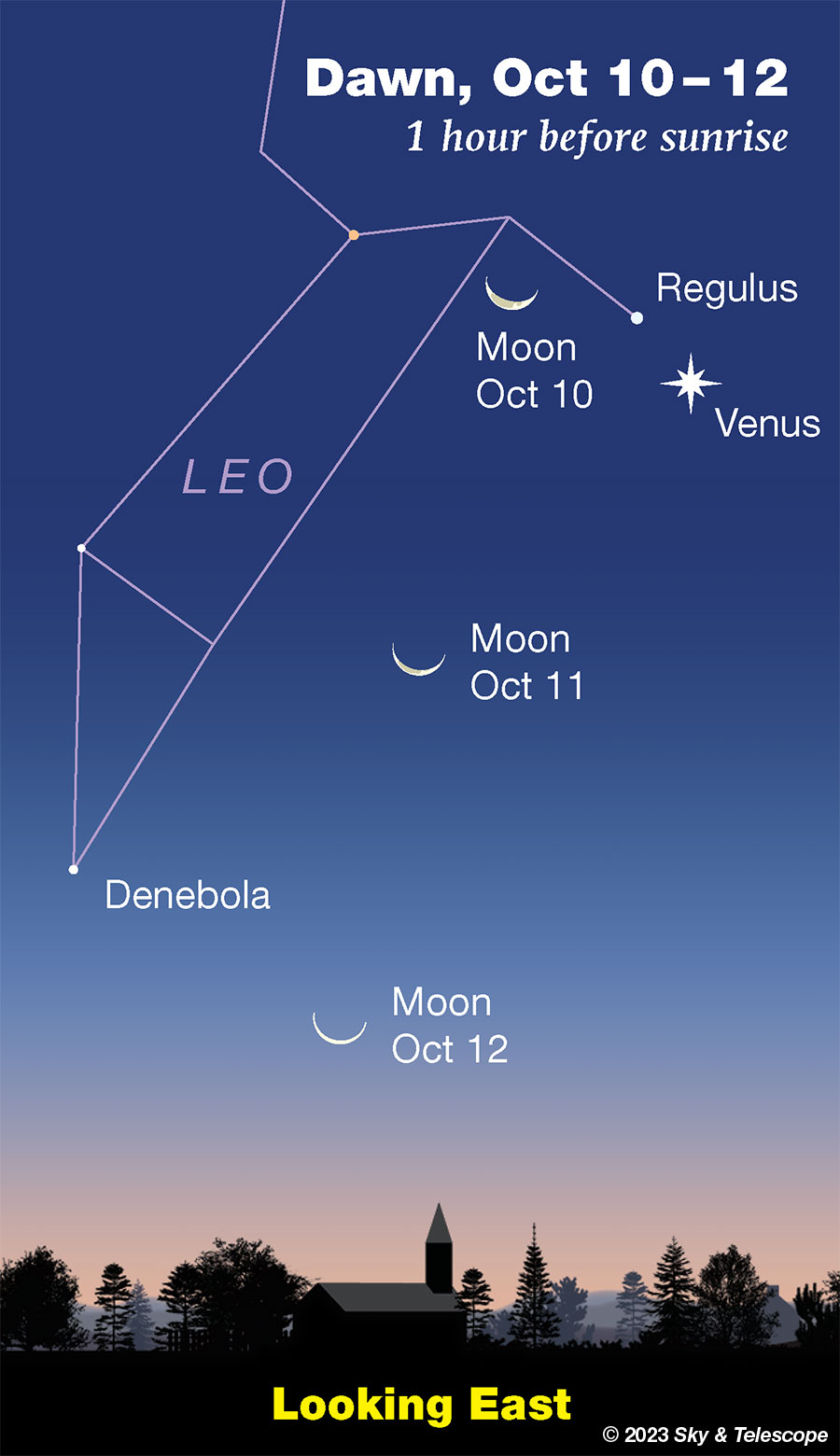

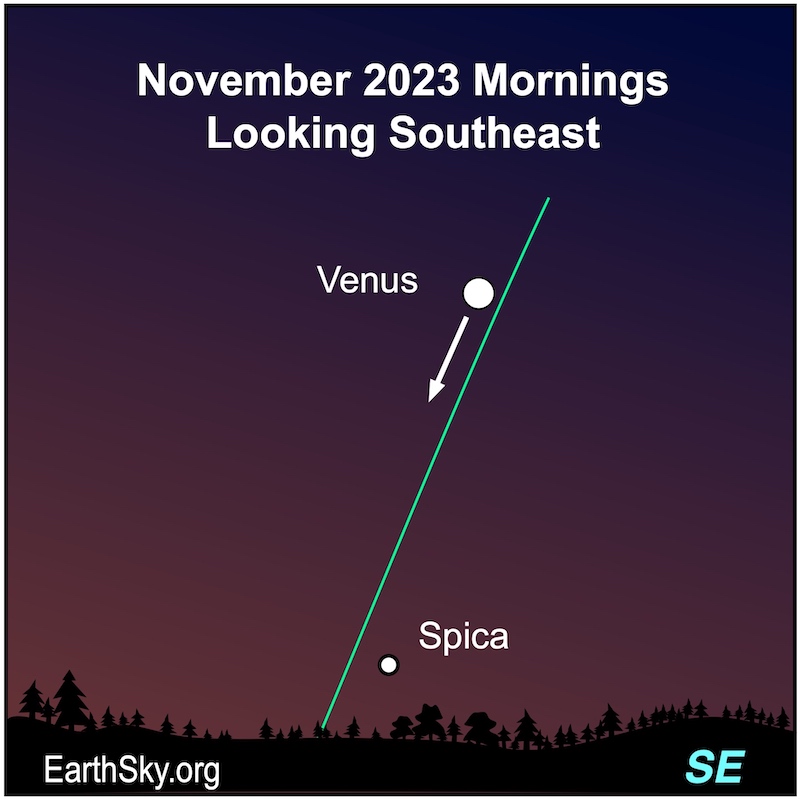

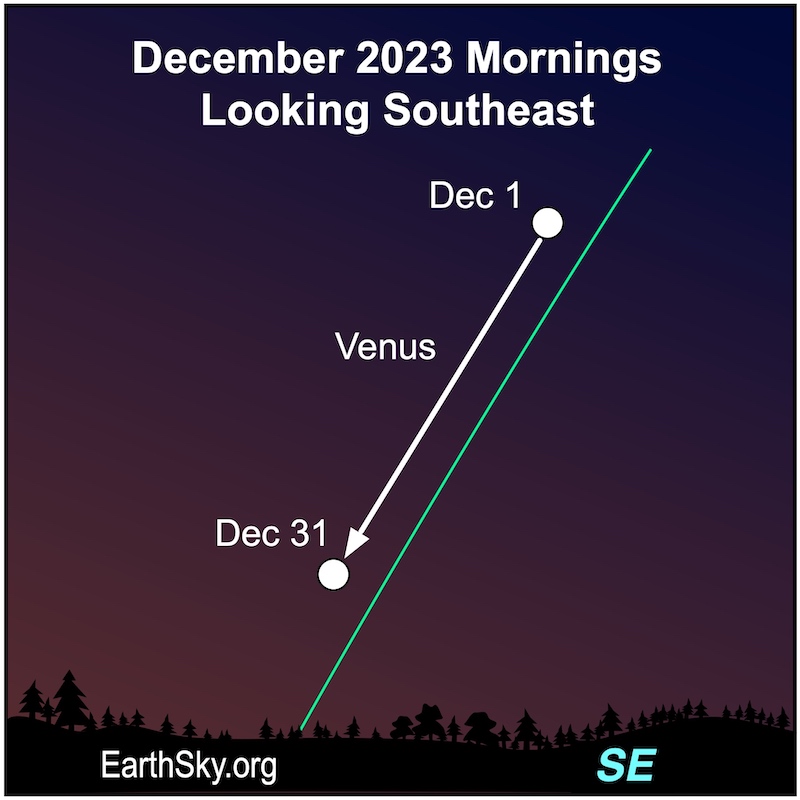

January mornings: Venus

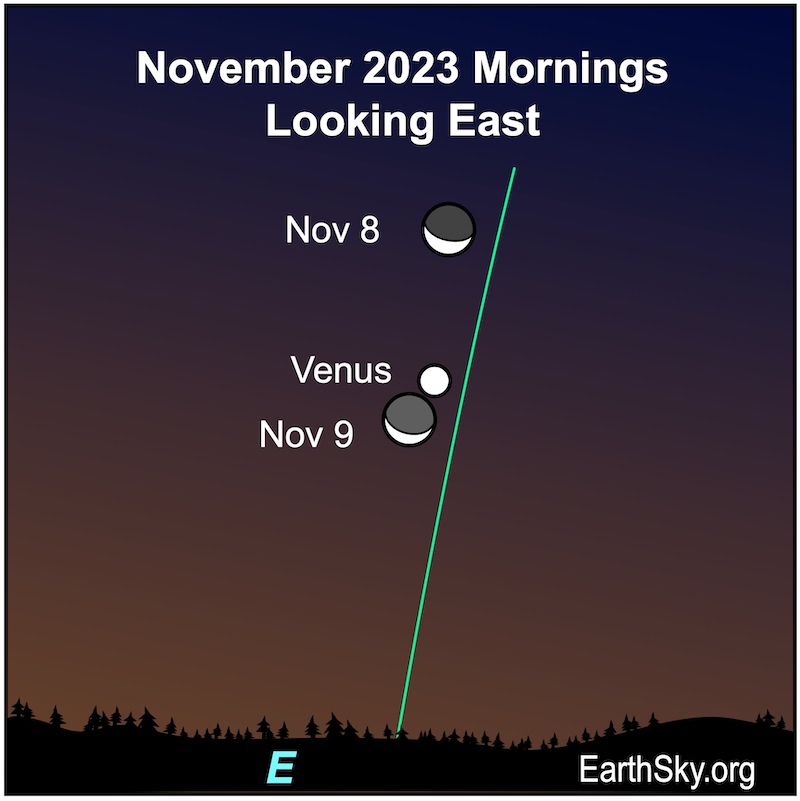

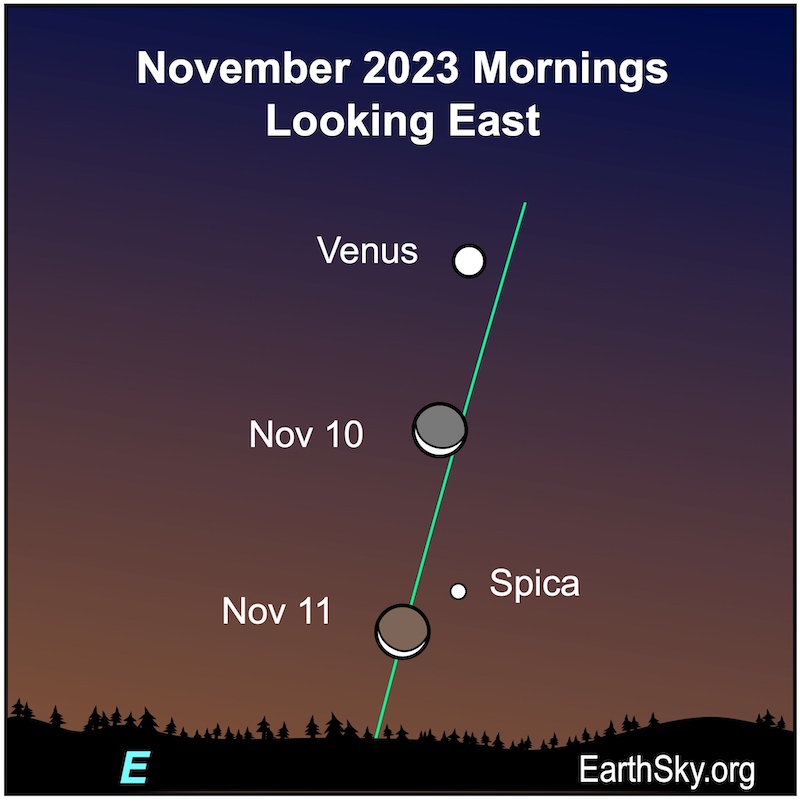

In January, the blazing light of Venus will continue to draw your attention in the morning sky. In fact, it will remain in the morning sky through March. However, it sinks lower each morning after it reached its greatest elongation – farthest distance from the sun in our morning sky – from the sun in October. Venus will shine all month at -4.0 magnitude. A lovely waning crescent moon will join Venus on the morning of January 8, 2024. The bright reddish star Antares will be nearby. Venus begins the month in the constellation Scorpius the Scorpion and will move into Ophiuchus the Serpent Bearer by mid-month. Then by month’s end, it will be in the constellation Sagittarius the Archer.

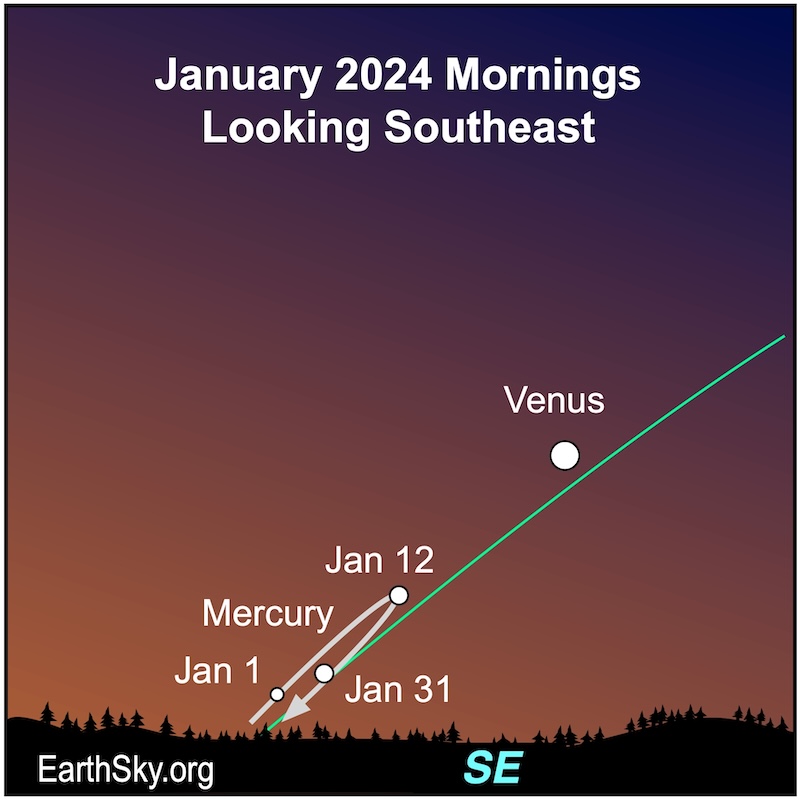

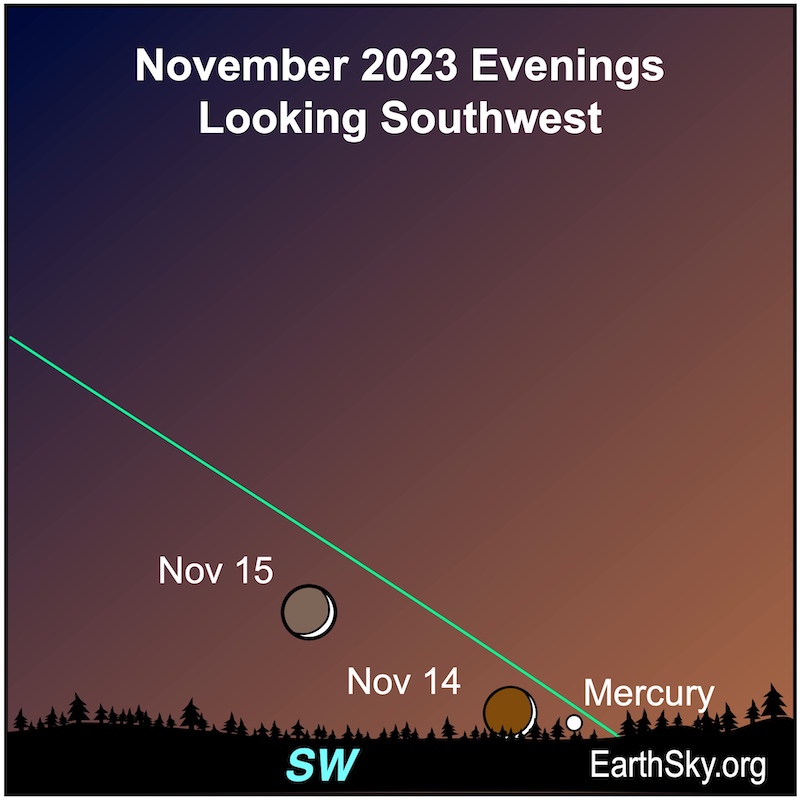

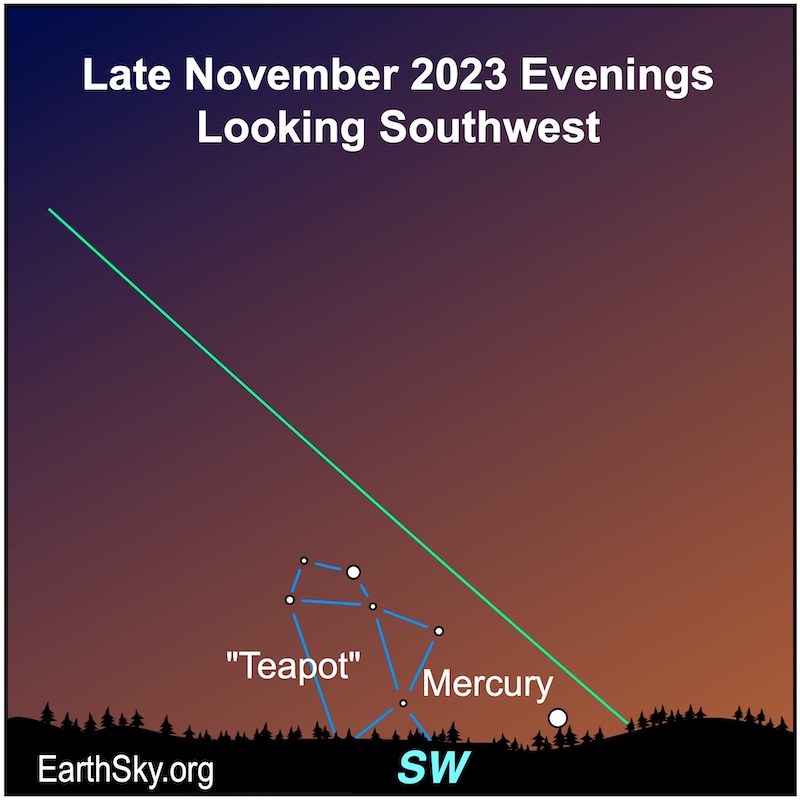

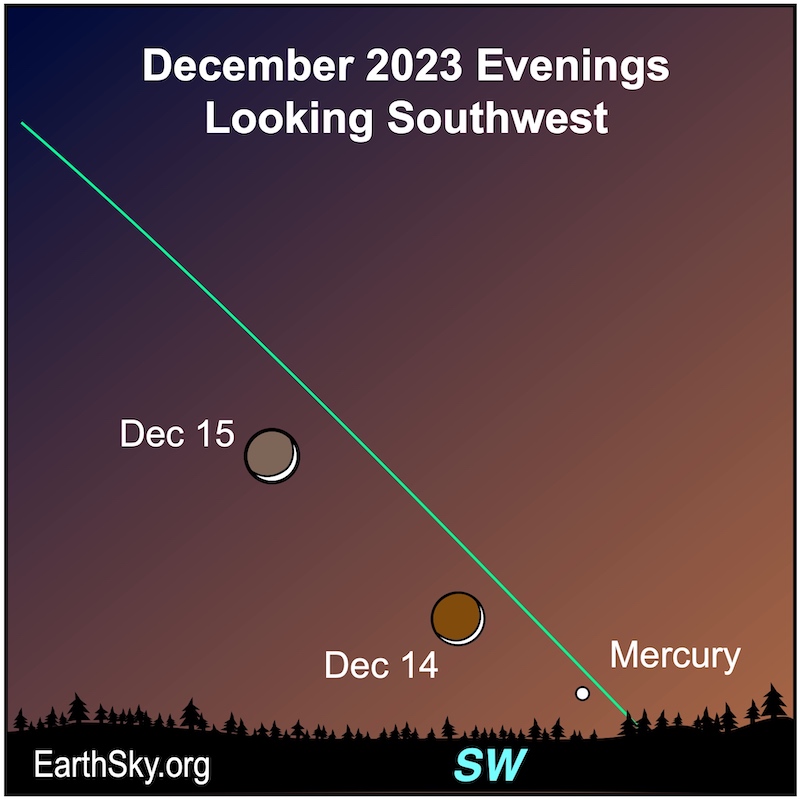

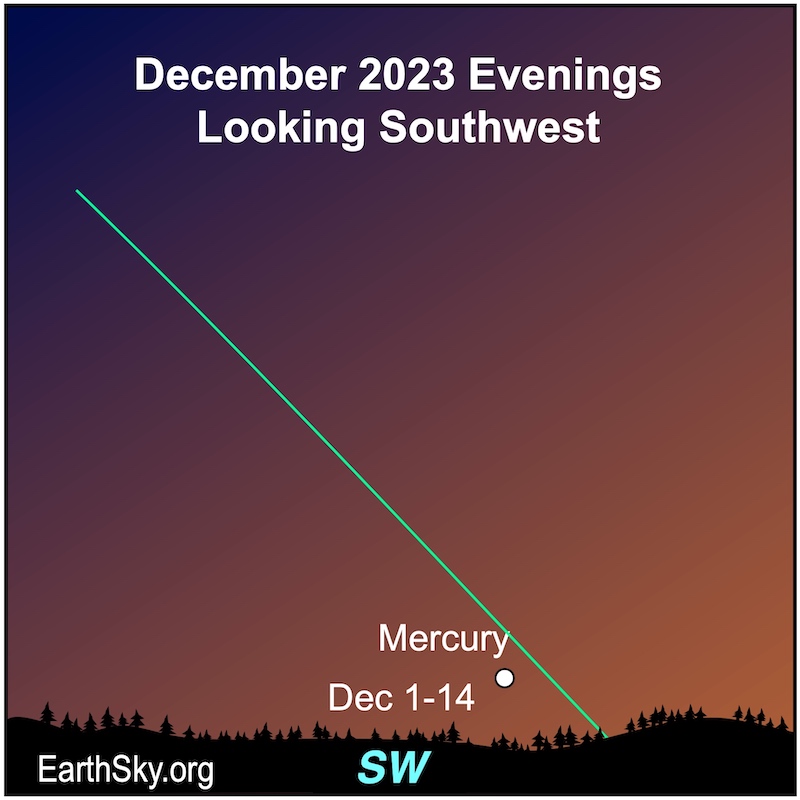

January mornings: Mercury

For viewers in the Northern Hemisphere, Mercury lies just above the horizon in the bright twilight shortly before sunrise in January. It’ll reach its greatest western elongation – farthest distance from the sun in our morning sky – on January 12, 2024. At best, Mercury reaches 24 degrees from the sun on that day. It will continue to brighten after greatest elongation and then disappear from the morning sky in February. The Southern Hemisphere will have the better view. The moon will lie near Mercury on the morning of January 9, 2024. Also, higher in the morning sky will be the brilliant light of the planet Venus.

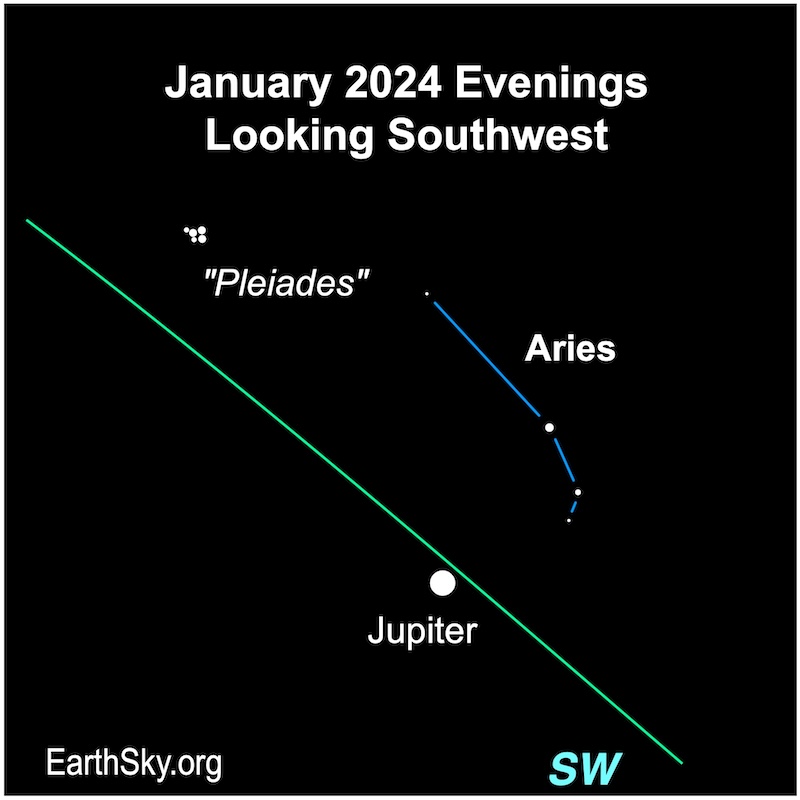

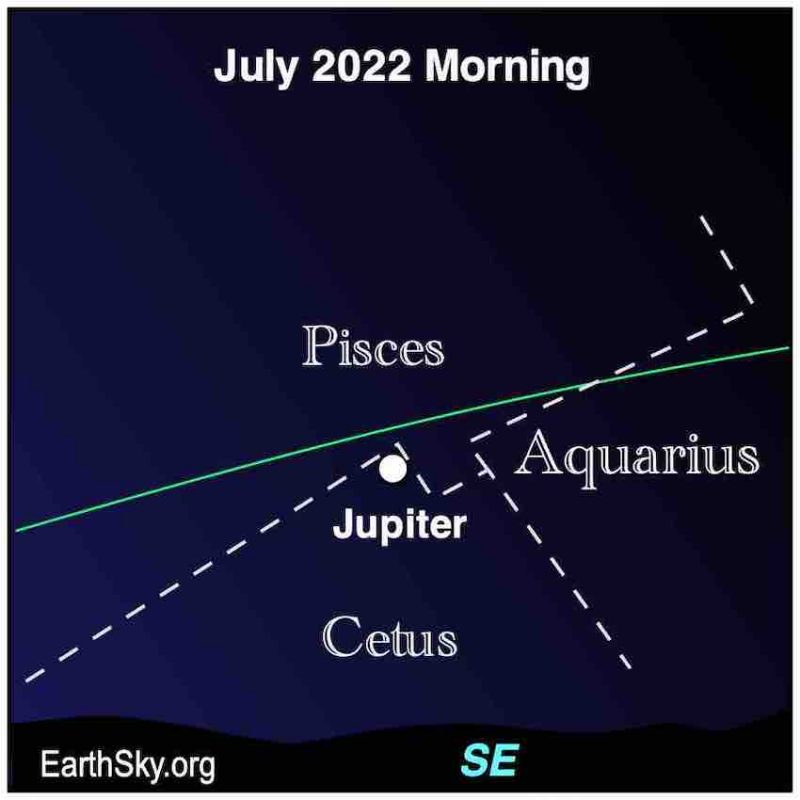

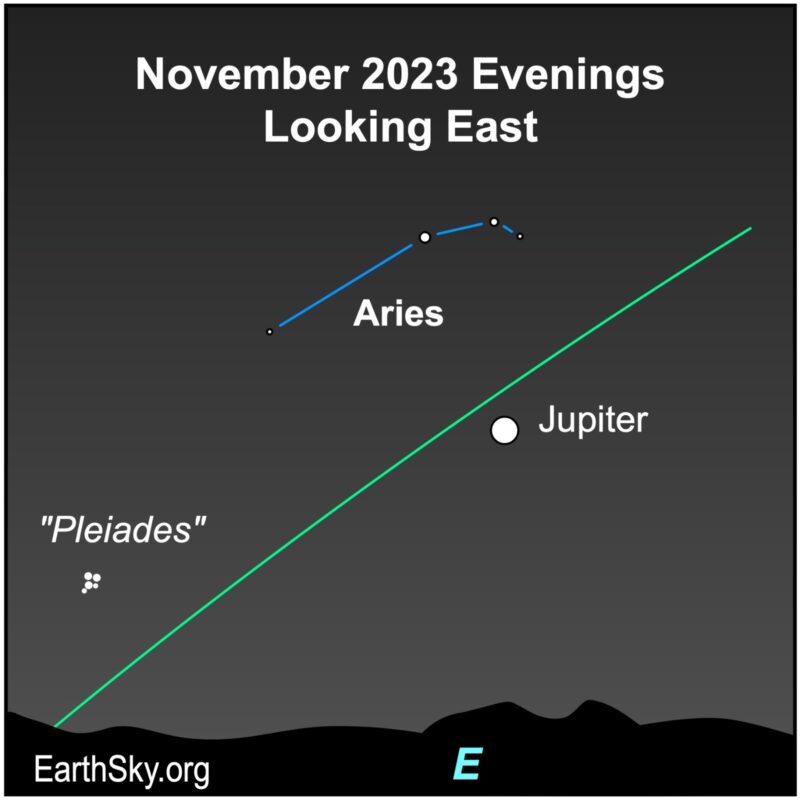

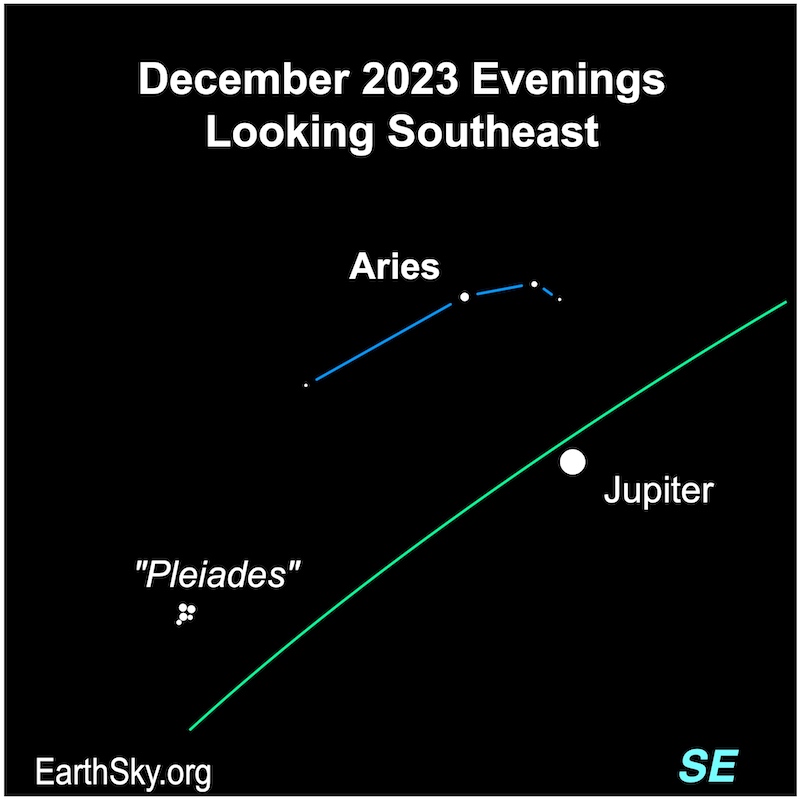

January evenings: Jupiter

Bright Jupiter will draw your attention until after midnight in January 2024. It will be very obvious high in the southern sky at sunset and will be visible until a few hours after midnight. It will shine near the pretty Pleiades star cluster in the constellation Taurus the Bull. Jupiter reached perihelion – or closest point to the Earth – in early November. And it reached opposition overnight on November 2-3, 2023, when we flew between it and the sun. So, as Jupiter recedes from Earth, it’ll fade a bit in our sky. It will lie in the dim constellation Aries the Ram. It will shine at -2.2 magnitudeby month’s end. The 1st quarter moon will float by Jupiter on January 18, 2024.

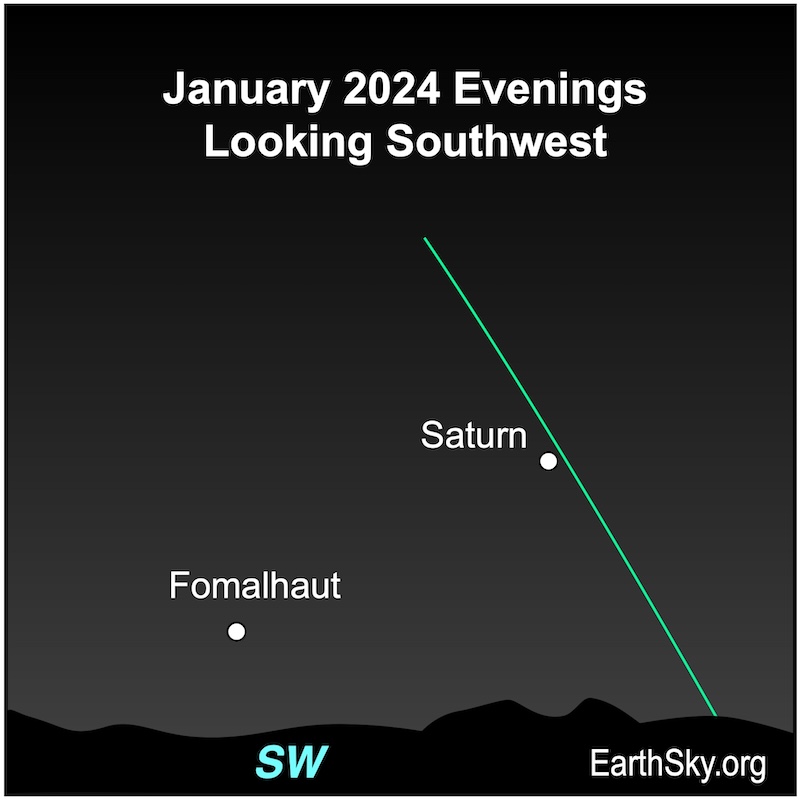

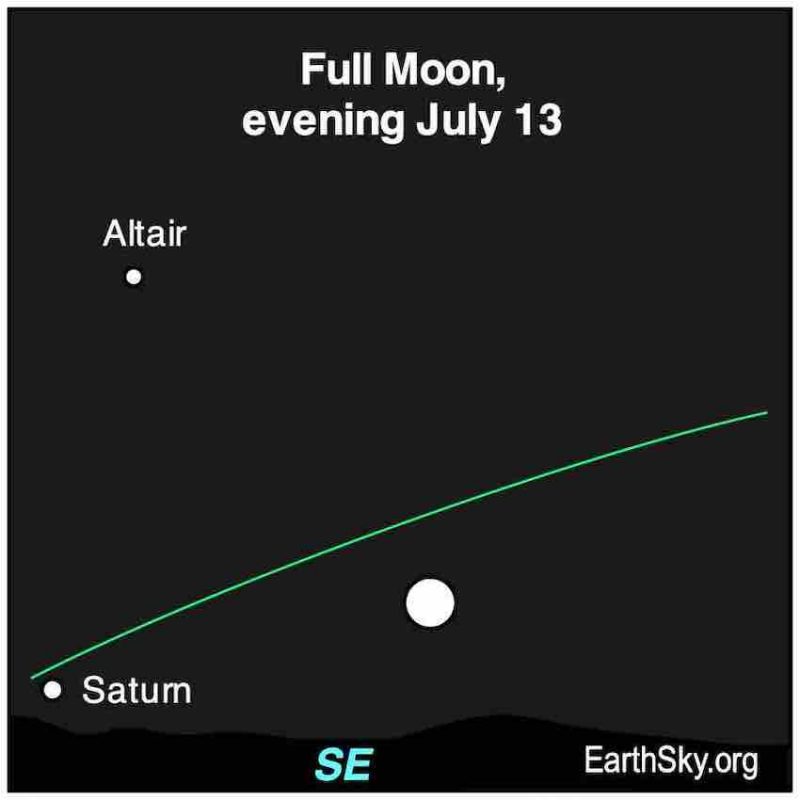

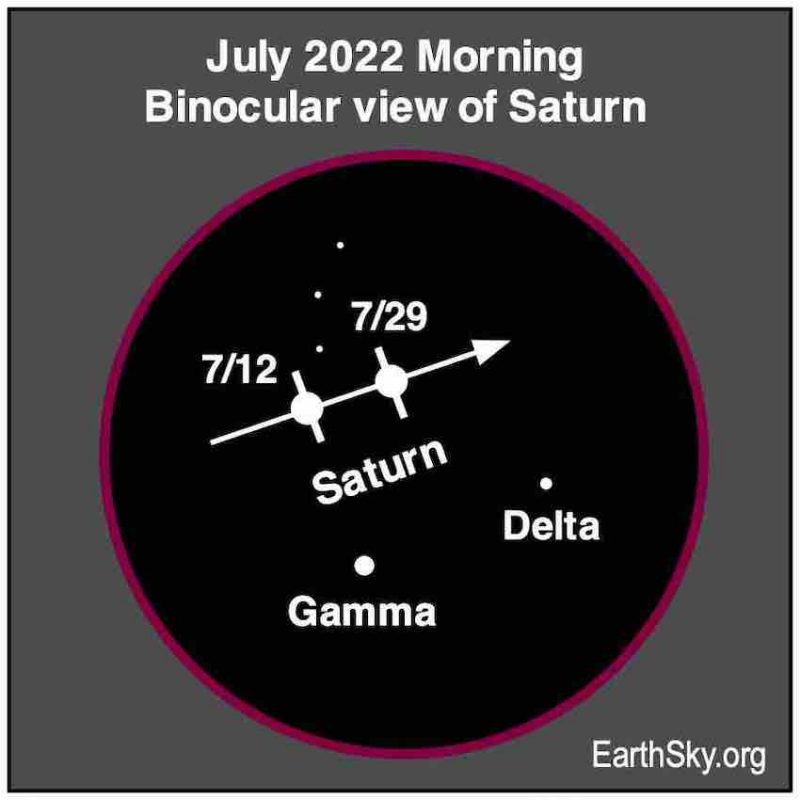

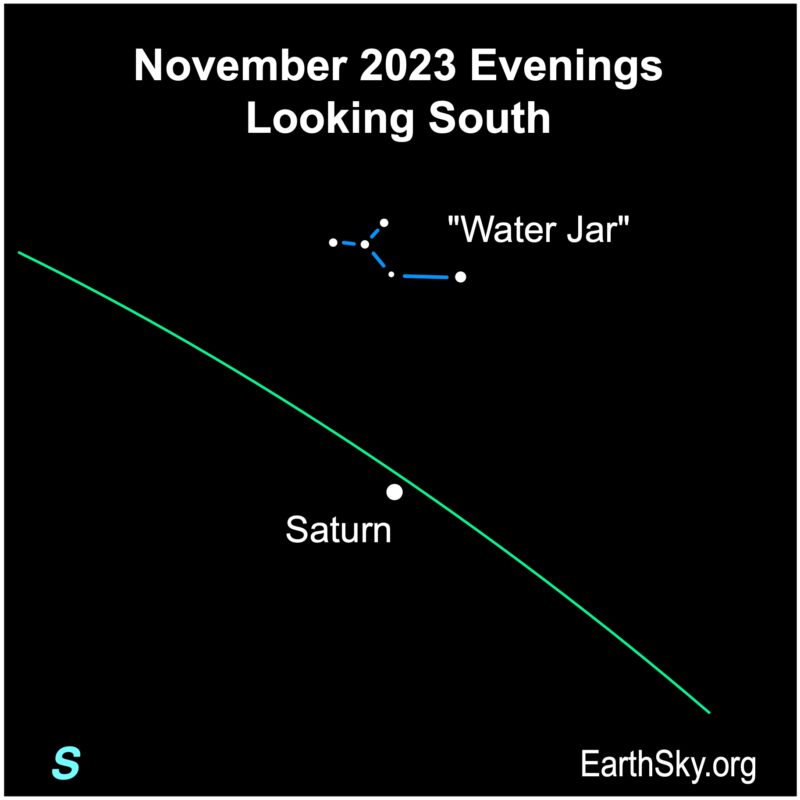

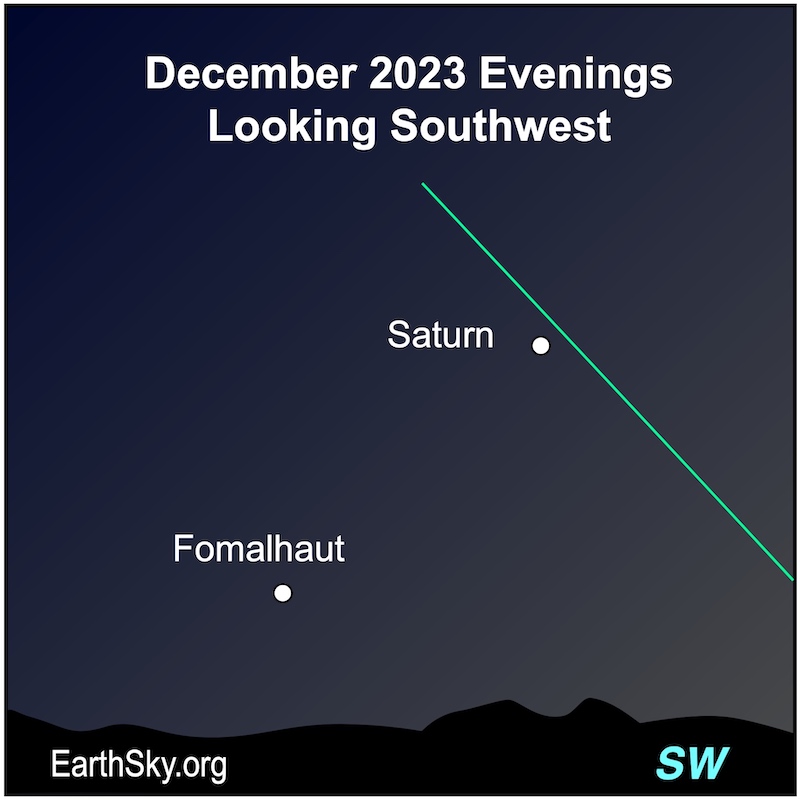

January evenings: Saturn

Golden Saturn will shine low in the southwest after sunset during January. It will be in the dim constellation Aquarius the Water Bearer. Our solar system’s beautiful ringed planet will be fading a bit this month as it recedes from Earth and will shine at +0.9 magnitude for most of the month. It shines near a star of similar brightness, Fomalhaut. Saturn will descend closer to the horizon each day, slipping out of the evening sky by February. The waxing crescent moon will visit Saturn on the evening of January 14, 2024. Saturn will set a few hours after the sun this month.

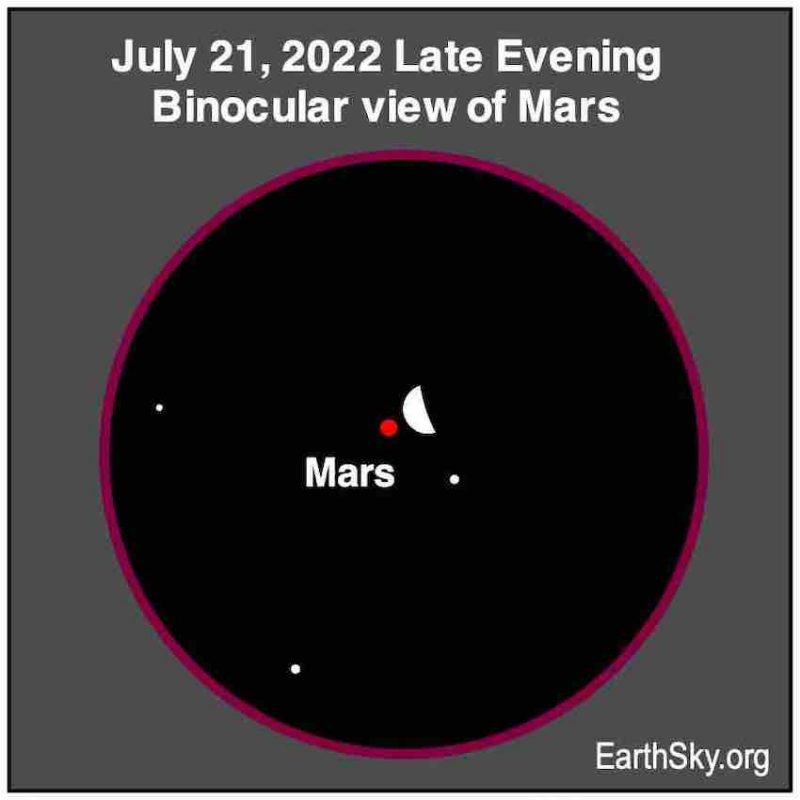

Where’s Mars?

Mars will be emerging low in the morning sky toward the end of the month. It’ll be a morning object for all of 2024. On the morning of January 27, 2024, it’ll be 0.2 degrees from Mercury. Mars will be within 0.6 degrees – as seen from Earth – of each of the other planets over a 7-month period. By the way, Mars will not reach opposition until January 2025. Opposition is when Earth flies between the sun and an outer planet and marks the the best time to see an outer planet. Mars reaches opposition about every two years, and some oppositions are better than others.

Thank you to all who submit images to EarthSky Community Photos! View community photos here. We love you all. Submit your photo here.

Looking for a dark sky? Check out EarthSky’s Best Places to Stargaze.

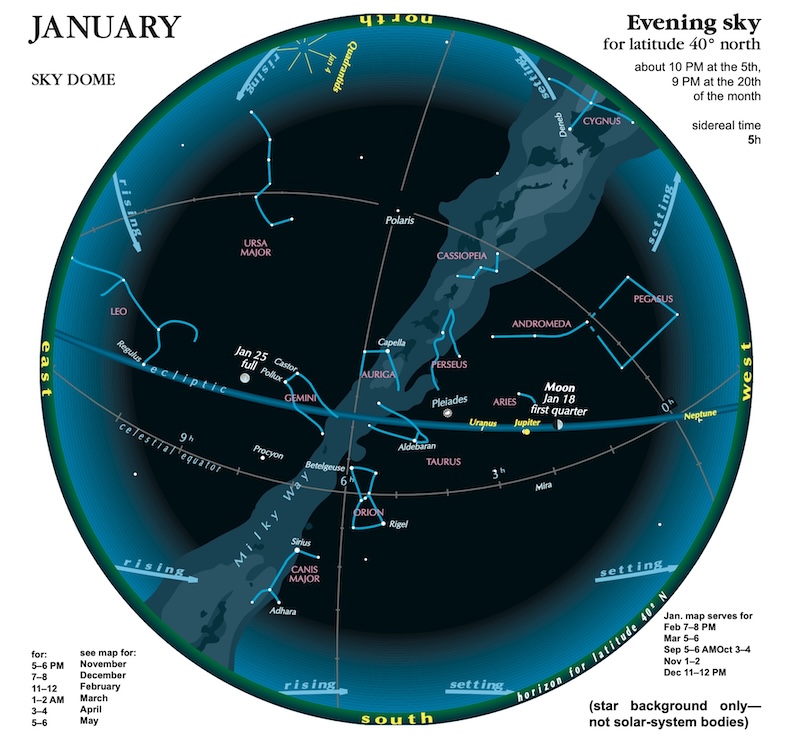

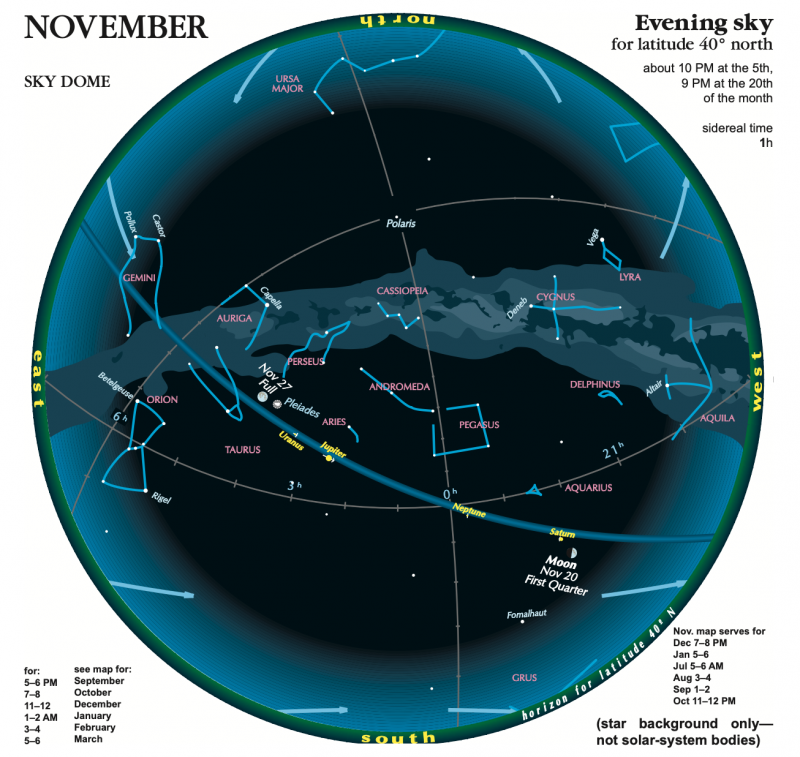

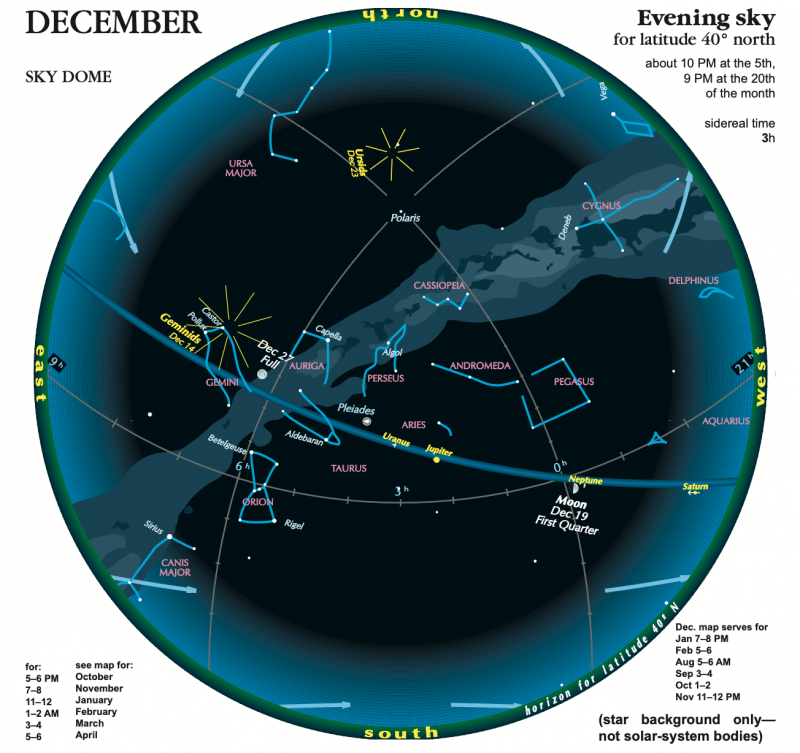

Sky dome maps for visible planets and night sky

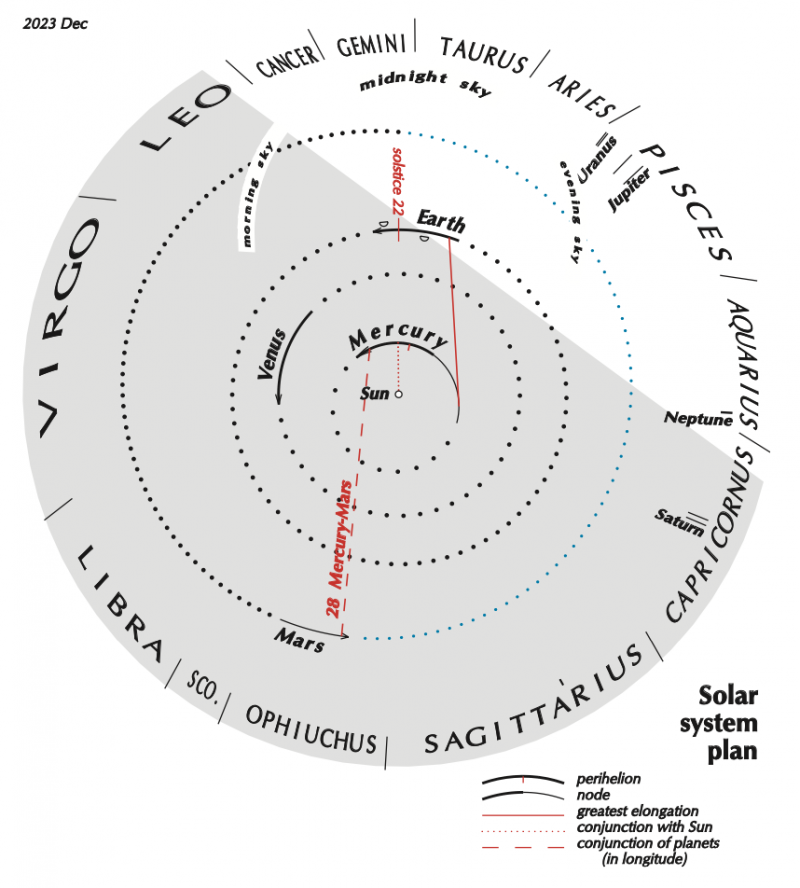

The sky dome maps come from master astronomy chart-maker Guy Ottewell. You’ll find charts like these for every month of 2023 in his Astronomical Calendar.

Guy Ottewell explains sky dome maps

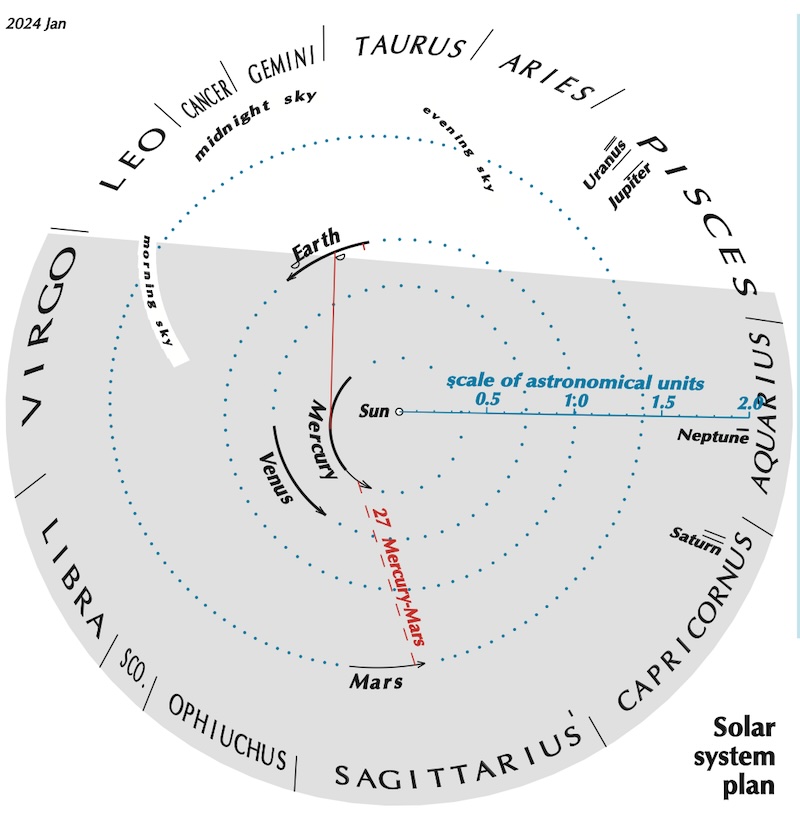

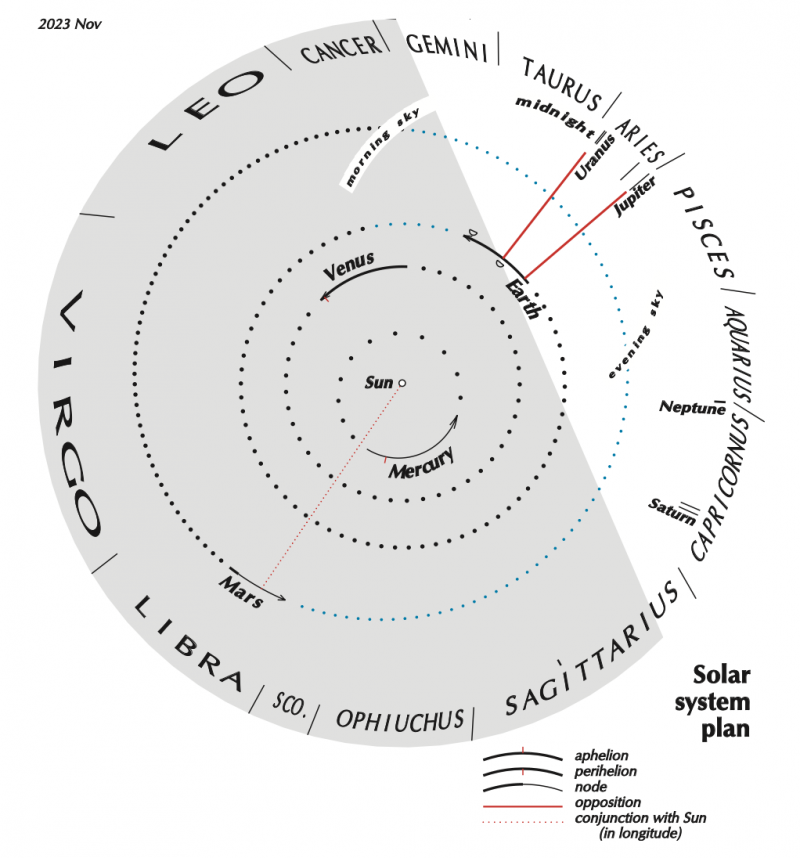

Heliocentric solar system planets

The sun-centered charts come from Guy Ottewell. You’ll find charts like these for every month of 2023 in his Astronomical Calendar.

Guy Ottewell explains heliocentric charts.

Some resources to enjoy

For more videos of great night sky events, visit EarthSky’s YouTube page.

Watch EarthSky’s video about Two Great Solar Eclipses Coming Up

Don’t miss anything. Subscribe to daily emails from EarthSky. It’s free!

Visit EarthSky’s Best Places to Stargaze to find a dark-sky location near you.

Post your own night sky photos at EarthSky Community Photos.

Translate Universal Time (UTC) to your time.

See the indispensable Observer’s Handbook, from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada.

Visit Stellarium-Web.org for precise views from your location.

Almanac: Bright Planets (rise and set times for your location).

Visit TheSkyLive for precise views from your location.

2) Planet Highlights:

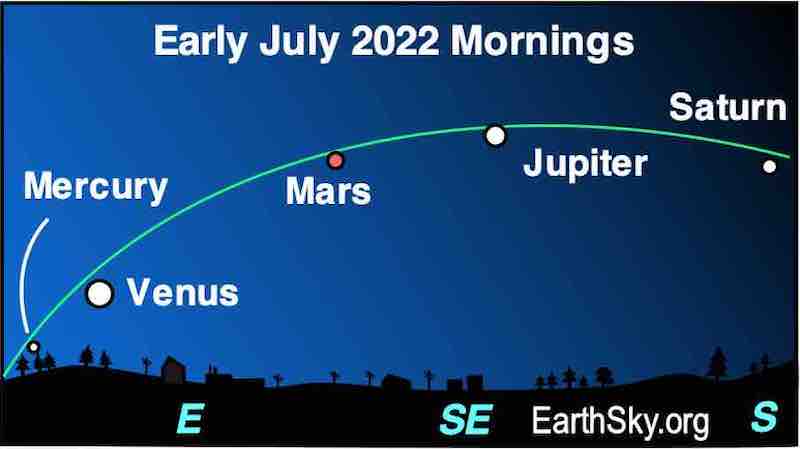

The new year finds orange Mars at its brightest of the entire year! Both Mars and Jupiter dominate the evening sky. Look about 45 minutes after sunset towards the southwest. First, spot Jupiter as it’s brighter than all the stars. Then look to Jupiter’s left (about 60 degrees) and a little higher in the sky to find the planet Mars.

Now look below and slightly right of Jupiter (a little less than 40 degrees) to see Saturn just above the southwest horizon. As the days pass, Saturn may be difficult to see so near the horizon; you’ll need a clear view.

Meanwhile, Venus is at its dimmest of 2023. However, Venus is on an upward trajectory, appearing higher and brighter each evening, climbing out of the sunset twilight by mid-month.

See Planet Rise and Set times for your location.

Visible Planets: Highlights

January 3: Don’t miss this super-close meeting of the Moon and orange Mars, still very brilliant since its opposition and closest-approach happened only a few weeks ago in early December. City lights can’t spoil this one. A backyard telescope can boost the fun by revealing the northern Martian polar cap and some dark surface markings.

January 4: It’s the year’s closest approach to our great star, aka the perihelion. This is the point in Earth’s orbit when it’s closest to the Sun, though it’s still about 91.4 million miles away!

January 21–22: Observers will enjoy watching Venus and Saturn draw closer every night. On the 21st, Venus is only a degree below Saturn. Then on the 22nd, the two planets meet—less than a quarter degree apart. Look low in the southwest at around 4:45 PM. Though just 10° high, which necessitates an ocean-flat horizon (don’t bother if hills, trees, or houses block the horizon in this direction), the extreme super-brilliance of Venus makes that Evening Star a don’t-miss target, especially with that little “star” (the planet Saturn) hovering next to it in the fading dusk.

January 23: Venus appears about a degree above Saturn. While not as close together tonight, the scene is more than compensated by the thin crescent Moon now to their upper left. A Three-For-One special! But quite low at 4:45 PM so once again you need a flat horizon.

January 24–25: On the 24th, the crescent Moon appears between Venus and Jupiter, and on the 25th, Jupiter is that brilliant “star” just above the Moon tonight. High up, easily seen from cities, and never mind watching the clock. Anytime after 5 PM will work.

January 30: The Moon closely meets Mars for the second time this month. Still in the constellation Taurus, look at how much that orange “star” has faded since its January 3 conjunction, as Earth keeps racing away from it at 66,000 mph.

Other features of this month’s sky:

JANUARY 1: BRIGHT SIRIUS

Begin January by finding bright Sirius, the Dog Star, in the night sky! Sirius is the brightest star above, so it’s easy to find. If you’re not sure, find the belt of the constellation Orion and follow it downward. Orion’s Belt always points to Sirius. Learn more about Sirius.

JANUARY: THE QUADRANTID METEORS

(courtesy of almanac.com and https://www.adlerplanetarium.org/blog/what-to-see-stargazing-tips-january-2022/)

The Quadrantids are the first major meteor shower of the year, peaking the night of Monday, January 3 into the morning of the 4th. Unfortunately, in 2023, the Moon will be 92% full, obscuring the fainter meteors. Your best bet is to view after the Moon sets on the 4th of January, just before dawn.

Full Moon (The “Wolf Moon”: Friday, January 6, at 6:09 P.M. EST)

Seasons of 2023 |

Astronomical Start |

Meteorological Start |

|---|---|---|

| SPRING | Saturday, March 20, 2:24 P.M. PDT | Monday, March 1 |

| SUMMER | Sunday, June 21, 7:58 A.M. PDT | Tuesday, June 1 |

| FALL | Wednesday, September 22, 11:50 P.M. PDT | Wednesday, September 1 |

| WINTER | Tuesday, December 21, 7:27 P.M. PST | Wednesday, December 1 |

2023 Eclipses

(courtesy of timeanddate.com)

Please go to the following link to learn where you can enjoy 2023 eclipses:

https://www.timeanddate.com/eclipse/2023

January 2023 Phenology:

Gray Whale Migration: Frequent Flyer Journeys

Giant mammals are now gliding past our coast on their journey south from feeding grounds in the Bering Sea to calving grounds near Baja California. Gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) migrate more than 12,000 miles each year. Given they migrate close to shore, you may be able to see them from land along the Sonoma coast, at Pt. Reyes, and in Big Sur. Watch for the low, puffy (some call them heart-shaped) spouts produced when the whales exhale — with Point Reyes National Seashore’s lighthouse one of the best venues to view this phenomenon.

By Sea & Shore: Elephant Seals Are Currently “Must See” Viewing

Northern Elephant Seals (Mirounga angustirostris) spend most of their life in the open ocean, diving up to 5,000 feet to feed on pelagic fish and squid. They come ashore only to mate, give birth, and molt their old skin and hair. By January, female Northern Elephant Seals have returned to breeding beaches to give birth. The one 75-pound pup she produces each year gains 10 pounds a day as it nurses on her extra-rich (50% fat!) milk. Pups typically nurse for 28 days. After the pups are weaned, females mate with one or more of the dominant males before leaving the beaches. By mid-March all the adults are gone, leaving the pups to fend for themselves. In the ultimate Survivor test, the pups (now called weaners) must learn to swim and catch fish on their own. Once they’ve mastered these basic skills, the pups take to the sea, heading north to feed off the coast of Washington and British Columbia. They won’t return to land until the fall. In the Bay Area, you can see elephant seals pups at Chimney Rock in Pt. Reyes, or on a naturalist-led tour (reservations required) at Año Nuevo State Reserve.

Stinky Blooms Delight Senses

While its name sounds like an unpleasant affliction, Fetid Adder’s Tongue (Scoliopus bigelovii) is actually a lovely wildflower. January is a good time to start searching for this diminutive lily relative along trails in redwood forests. Three small, cream and maroon-striped sepals surround three delicate upturned petals and three stamens. The odorous blooms fade quickly but the dramatic mottled leaves persist for several months.

After tiny fungus gnats pollinate the flowers, the seed capsules’ weight pulls the stems to the ground, giving the plant its other common name, “Slink Pod.” Slugs and ants may help spread seeds. In Marin County, look for Fetid Adder’s Tongue in Muir Woods National Monument, Mount Tamalpais (Blithedale Canyon, Cataract Gulch, Fish Grade), Bolinas Ridge, San Geronimo Ridge, and San Rafael Hills. On the Peninsula, it may be found in early January along Crystal Springs Trail in Huddart County Park (Woodside) and later in the month along the Hazelnut Trail in San Pedro County Park (Pacifica).

Early Wildflower Bloom: 2023 Forbs/Ephemerals

Given our ample rainfall in 2022 and in early January, 2023, it will soon be time to enjoy blooming wildflowers. Where are excellent spots to enjoy their beauty and dozens of other colorful wildflowers? Check out:

Annadel State Park, Santa Rosa, CA, Sonoma County

Chimney Rock (near the Lighthouse, Outer Point, Point Reyes National Seashore), Inverness, CA, Marin Co.

Edgewood County Park (south of SF), off I-280 and adjacent to it, San Mateo County

Black Diamond Mines Regional Park (ebparks.org), near Antioch and, especially, on Somersville Road (that exits off of Highway 4), East Bay of SF Bay

Are Herring Here Yet?

Please note…..For herring infusion updates into the SF Bay, see: https://cdfwherring.wordpress.com/

Watch for frenetic collections of gulls, scoters, cormorants, and sea lions within shallow spots of the Bay. Their presence is an indication that Pacific Herring have made their annual arrival. As early as November, yet sometimes waiting until this time of year, adult males and females seek spawning (i.e., egg laying) locations in shallow intertidal and subtidal waters. A single female may lay as many as 20,000 eggs in one spawn following ventral contact with submerged substrates such as eel grass. Why spawning begins is not understood, but some researchers believe the male initiates the process by release of milt (the seminal fluid of herring) that contains a pheromone that stimulates a female to begin egg laying. Egg laying appears to be collective so that an entire school may spawn in the period of a few hours, producing an egg density of up to 6,000,000 eggs per square meter.

Pop Quiz:

Which bird species is probably the earliest breeder in Marin County?

Answer: Early nesting Anna’s hummingbirds may lay eggs this month or, in some cases, last month. More information about hummingbirds in California appears in the next account.

Note that some Anna’s Hummingbirds exhibit nesting/courtship behavior by October. I noticed this phenomenon in my backyard’s forested/open woods area this past autumn. The loud “pop” of diving males was heard regularly in our autumn landscape.

Of course, a second (and third brood) of Anna’s may result from the most prolific breeders of this species. Not that any male Anna’s would know about their brethren. That’s because the male Anna’s never bonds with his female partners. All males merely provide the “seed” by which newcomers develop in females, but they are left to fend for themselves on the nest. Males opt for quickly exiting Stage Left after impregnating their suitors. For this reason, you might say Anna’s males take “Speed Dating” to a new avian level and meaning.

Hummingbirds In California: Early Breeders

Anna’s Hummingbirds, year-round residents in northern California (and throughout much of the state), may already be laying eggs — perhaps initiating courtship and/or nesting as early as December (!). Some early-nesting females will play hostess to two broods during the breeding season, with second clutches hatching as late as mid-August. Peak breeding and greatest nest abundance occurs in May. Amazing but true, this year’s initial breeding cycle began in October in Marin County where I live. That’s when I began seeing courtship dances by male Anna’s on my land. Whether the females were receptive then is another question that remains unproven.

Research studies have indicated this hummer species memorizes and learns a song in its first year of life, similar to the behavior of most songbirds. Allen’s Hummingbirds, which breeds from s. California to s. Oregon, begin to arrive annually in the SF Bay Area early as mid-January after spending the winter in Baja California and Chihuahua in Mexico. Some of the arrivals may remain to breed in the area.

Other populations of this species are year-round residents in southern California.

Their preferred habitat is canyon woodlands, brush and highland meadows. This species breeds in the Bay Area, but by the end of July many have dispersed and/or left the Bay Area, and in mid- to late-August most of the species’ population has migrated south.

Rufous Hummingbirds are seen only during migration in California, except for the extreme northern part of the state where their breeding area begins (and stretches north throughout much of Oregon, all of Washington, and into parts of Idaho, Montana and Wyoming, as well as into British Columbia, Alberta and southeast Alaska). In Marin County, expect to begin seeing this transient species as early as mid-February, with a peak presence from mid-March through mid-April. By the end of May, Rufous are typically absent in Marin Co. The autumn migration spectrum is from mid-June through September in Marin Co., especially outside the County amid the Inner Coast Ranges, but sometimes along the coast, too.

Other hummingbirds occur in California, of course, but the aforementioned three species are usually the most common ones to see in the Bay Area/Marin County. Calliope, and Costa’s Hummingbird, and Black-Chinned Hummingbird are sometimes observed in the Bay Area, though the initial two of these three species is considered a “casual visitor” to Marin County (and Black-Chinned the most rare, yet still considered a “casual visitor”) — with all three occasional to common casual visitors in more eastward Bay Area counties.

See above for more information about the breeding dynamics of Anna’s Hummingbird in N. CA/the Bay Area.

Swallows During Winter In Northern California?

They are never a common sight, but it’s possible to see the following swallow species in Marin County (and the Bay Area) during the winter in the following order, from most common to rare: Tree (now annual during the non-breeding season in Marin County), Barn (not always annual, but typically seen during most “winters” in the Bay Area), and Violet-green (likewise, not always annual during the non-breeding season, yet often reported from November-February before migrants return to breed in the Bay Area). Our other northern California summer residents — Northern Rough-Winged, Cliff, and Bank — are considered rare to absent in January, though they may return on migration by no later than the end February during some to most years.

Purple Martin are also typically absent from our area in January and February. As for swift species, White-Throated are by far the most typical one to see, if any, from January-March, and they are considered year-round residents in the SF Bay Area. Vaux’s return on migration in April, while the more uncommon to “casual visitor” swift species — Chimney and Black — are usually spotted (if at all) from May through mid-October in northern California.

Checklists specific to a Bay Area region sometimes miss indicating the aforementioned swallows are potential winter sightings. I’ve noticed, for example, more reports by excellent birders in recent years of over-wintering Tree and Barn in the Bay Area. To wit, in the past, many of the same birders in the Bay Area used to believe that Tree Swallow completely left the Bay Area as an autumn migrant. Now, that dynamic has changed. Instead, Tree Swallow (and, increasingly, Barn Swallow) are considered a regular non-breeding season inhabitant (in small numbers) throughout the Bay Area (e.g., Las Gallinas Wildlife Ponds, San Rafael, Marin Co.).

Hibernating Birds in Our Area?

Not exactly. But our Common Poorwill (Phalaenoptilus nuttallii californicus) (also called the Dusky Common Poorwill as the nominate race among five subspecies in the species) does exhibit winter torpor. According to Wikipedia, the Common Poorwill is the only bird known to go into torpor for extended periods (weeks to months). Such an extended period of torpor is close to a state of hibernation, a condition not known among most other birds. It was described definitively by Dr. Edmund Jaeger in 1948 based on a Poorwill he discovered hibernating in the Chuckwalla Mountains of California in 1946.

By the way, don’t let this bird’s name fool you. It’s never “common” where we live in northern California. In Marin County, one of the best spots to see Common Poorwill is along open areas, hillsides and talus slopes on Mount Tamalpais. More typical, I hear this bird’s vocalizations only and, if I’m lucky, then find it. Tilden Park in Berkeley periodically hosts this species, too. My BEST success for finding this species is in Lake County’s higher altitude spots as they flee from perches on the road at dawn while I’m riding on backroads.

February, 2024

Sky Watch:

1) Moon & Planet Rise & Set Times

Go to: https://www.timeanddate.com/astronomy/night/

Then type in your location to see planet highlights for each day of the month.

For my area in February, 2024, here’s planet viewing information:

| Planetrise/Planetset, Tue, Feb 1, 2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planet | Rise | Set | Meridian | Comment |

| Mercury | Wed 6:00 am | Wed 4:03 pm | Wed 11:01 am | Difficult to see |

| Venus | Wed 4:56 am | Wed 3:15 pm | Wed 10:06 am | Great visibility |

| Mars | Wed 5:05 am | Wed 2:30 pm | Wed 9:47 am | Average visibility |

| Jupiter | Tue 8:28 am | Tue 7:31 pm | Tue 1:59 pm | Average visibility |

| Saturn | Tue 7:28 am | Tue 5:42 pm | Tue 12:35 pm | Extremely difficult to see |

| Uranus | Tue 11:06 am | Wed 12:45 am | Tue 5:55 pm | Difficult to see |

| Neptune | Tue 9:04 am | Tue 8:40 pm | Tue 2:52 pm | Very difficult to see |

All times are Pacific Standard Time at sea level.

Tonight’s Sky in Novato, Feb 1 – Feb 2, 2022 (7 planets visible)

Mercury rise and set in Novato

Fairly close to the Sun. Visible around sunrise and sunset only.

Wed, Feb 2↑6:00 am

Venus rise and set in Novato

View before sunrise.

Wed, Feb 2↑4:56 am

Mars rise and set in Novato

View before sunrise.

Wed, Feb 2↑5:05 am

Jupiter rise and set in Novato

View just after sunset.

Tue, Feb 1↓7:31 pm

Saturn rise and set in Novato

Very close to Sun, hard or impossible to see.

Tue, Feb 1↓5:42 pm

Uranus rise and set in Novato

View after sunset. Bring binoculars.

Wed, Feb 2↓12:45 am

Neptune rise and set in Novato

View after sunset. Use binoculars.

Tue, Feb 1↓8:40 pm

2) Planet Highlights (courtesy http://www.almanac.com):

- Early this month, Saturn materializes as a low morning star just before sunrise, joining higher-up Jupiter and Mars, all in Sagittarius. These three superior planets bunch closer together as the month progresses. It’s probably easiest to spot bright Jupiter; then look for Mars above and Saturn below.

- Venus: After sunset, Venus pops out at you as the brightest thing in the western sky. This shining beacon will continue to dazzle through the entire month as dusk falls. In the second half of the month, Venus is really the only bright object that appears in the west after sunset. It’s impossible to miss.

- Mercury: Look far to the lower right of Venus. Any “star” you see down there is Mercury! Look near the sunset point on the horizon shortly after sunset. During this month’s first 12 days, Mercury has its best showing of 2020 at a very bright magnitude 0, far below the more dazzling Venus, which stands 10 degrees high 40 minutes after local sunset. You no longer need telescope or binocoluars to find Mercury (though binoculars will help).

February Moon and Planet Pairings

- On February 18, the waning crescent Moon offers a strikingly close conjunction with Mars before dawn. Then on the 19th, the Moon passes to the right of Jupiter to be just below Saturn on the 20th, providing easy identification of these two gas giants that will astonish the world in December.

- On February 27 and 28, the waxing crescent moon pairs with bright Venus.

February 16-18, 2024:

Backyard Birdwatchers Unite As Citizen Scientists — The Annual Great Backyard Birds Count

Each February, backyard birdwatchers help scientists and bird enthusiasts learn more about bird populations across the United States by participating in The Great Backyard Bird Count, a joint project of the Cornell Lab or Ornithology and the Audubon Society. So, if you want to count your backyard birds and report your observations online, go learn more at: birdcount.org

Bird Classification Changes For 2024?

We’ll know as birders by this June or July, 2024 whether one or more of the following proposals are approved, per this link, if you wish to review them:

2024 Proposals

Insects Awakening:

Ladybird Beetles Becoming Active After Winter Slumber (Dormancy)

(Source: http://lancaster.unl.edu/hort/articles/2002/winterbugs.shtml)

Did you know that insects migrate? In May and June, one of our most familiar six-legged residents, the Convergent Ladybird Beetle (Hippodamia convergens), moves from the hot, dry valleys to the cooler climes of the High Sierra and Coast Ranges. Once in the mountains, the adult beetles bulk up in preparation for hibernation by eating pollen and nectar. When temperatures dip in the fall, the beetles follow river valleys to lower elevations (2,000-5,000 ft.), where they gather in huge numbers and take shelter for the winter under leaf litter, inside tree hollows, and in any other protected location. When the weather begins to warm up in late February and early March, tens of thousands of ladybird beetles emerge from hibernation and head back to the valleys.

Why so much movement? Aphids are the answer. Larval ladybirds are voracious carnivores, gobbling up to 50 aphids a day. Before home gardeners and farmers started artificially introducing water to the landscape, aphids were only present during the rainy season. So ladybird beetles evolved to exploit this seasonal abundance, timing their arrival in the valley and subsequent egg-laying to coincide with the early spring’s aphid population explosion.

Each ladybird beetle lives for only one year. After mating and laying eggs (usually by May), the adults die, making way for the next generation.

Heads Down: Looking for Newts On The Loose

(Source: http://amphibiaweb.org/cgi-bin/amphib_query?where-genus=Taricha&where-species=torosa)

In the San Francisco Bay Area, mature California Newt (Taricha torosa) individuals begin their annual migration to breeding ponds and streams in December and continue migrating until the end of this month. Look for these intrepid amphibians on land during wet weather near deep, slow pools. The East Bay’s Tilden Park and Sunol Regional Wilderness are two local Hot Spots.

In fact, Tilden’s South Park Drive is such a superhighway of amphibian traffic (as they cross the road while oblivious to the approaching death march of vehicle tires) that park officials close it from November-March in order to protect newts.

The California newt embraces its amphibian activity in a fast-forward lifestyle. Seeing them amble about the landscape now is rare because for the vast majority of the year, they’re underground or in burrows/logs/leaf litter, etc. Peak viewing times correspond to rainy nights, as they seek mates and lay their eggs in ponds or streams (such as Tilden’s habitats).

Mission accomplished above ground, adults retreat from the water quickly after breeding, and spend the dry summer months hunkered down while aestivating (“hibernating”) away from our view. Likewise, young (larval) newts develop in water. As water supplies dwindle, larvae begin to change into adults (metamorphosis). Young newts leave the water in later summer or fall, spend the next few years on land, and return to the water to breed after reaching maturity.,

When do young mature and become adults? We don’ know. Researchers who study newts in the field have not identified the age of sexual maturity: datasets vary from three to eight years.

California Newts can live for more than 20 years. This longevity is no doubt aided by their extreme toxicity. Adults, embryos and eggs contain tetrodotoxin (TTX), a strong and potentially deadly neurotoxin. Larvae, however, do not posses TTX, making them an important food source for animals such as garter snakes. To be on the safe side, say hello to these colorful newts if you find them crossing the road, but don’t give them a kiss for good luck.

Wildflowers Rising To The Occasion

Watch now for more than a dozen early wildflowers opening their blossoms in a variety of habitats. Within coast live oak/California bay forests, you’re likely to see ground iris, Douglas iris, milkmaids, hounds tongue, mission bells, and California buttercup.

An excellent Web site to track the bloom of spring wildflowers is compiled and maintained by writer/photographer Carol Leigh. To see reports of the latest sightings or to announce your own discoveries, visit:

http://calphoto.com/wflower.htm or see the Marin Native Plant Society’s home page where wildflower enthusiasts post their “first of season” sightings.

Loud Waterfalls Announce The Season

Prime time viewing of the Bay Area’s and northern California’s ample waterfalls are a delight to the senses. What could be more invigorating and awe-inspiring than to feel the powerful force of liquid Earth bombarding the placid landscape? Looking up at the roaring display of frenetic molecules in motion within a waterfall, it’s easy to lose track of time. You’re simply “there,” and life is good. Your hypnotized gaze is proof that the best things in life are free. Some of the best locations for viewing waterfalls in our area appear in a Web site: http://www.norcalhostels.org//news/springtime-hikes-waterfalls-marin-county

A different angle is to think how loud, rushing water along your trail walk may challenge your ability to successfully converse with a trailside partner. After a few switchbacks of dialogue that include “what” and “sorry,” you decide there’s a better solution than yelling and screaming. You decide to surrender. A hike with the mute button “on” is not all bad. You let the anarchic accompaniment of water be your solace, a step-by-step meditation.

Loud Waterfalls, Cacophonous Creeks, And Bird Song

As an extension from the previous entry above, consider the following ecologic mystery while you’re walking beside a creek that emits an incessant refrain of rushing water: Does the loud sound affect singing birds and their ability to hear each other while establishing territories and attempting to attract mates along bottomland areas? The answer is only partially understood. In early winter, the question is invalid when no singing bird species in our area have yet begun to use their voices to attract mates or defend territories.

But conditions soon change when February arrives. In particular, now’s the time to ponder whether Orange-Crowned Warbler males (that may begin arriving in late February in our area) are negatively impacted by the cacophonous presence of water? Does the noisy environs affect their ability to successfully complete their appointed season’s life cycle? And what about Oak Titmouse, Bewick’s Wren, and Hutton’s Vireo — all of which are often singing in February and beyond within or nearby in upland areas within earshot of noisy bottomlands? Do all of these bird species have to wait until March and April and beyond to attract a mate that can finally better hear them? Or do they simply abandon a percussive bottomland area for more quiet nesting areas elsewhere that offer similar habitat conditions? The answer is a qualified “yes.” At least one streamside study has shown birds upland and more removed from loud streams have an easier time hearing the companion birds with which they share the same habitat. The article suggests upland birds more successfully find mates and complete their breeding cycle with newborns fledgling from nests.

Sea Urchins: Low Tide Lookout

This month and next, watch for red sea urchins (a four-inch echinoderm) during low tides along rocky stretches of the northern California coast. Spawning occurs now through March, and their populations appear to be flourishing due in part to the increasing absence of predators (such as sea otters) in parts of the ranges where both these critters live.

Returning Migrants: Premiering Now

Early returning birds that you may now begin seeing include several swallow species (beyond populations that did not leave the Marin County area/Bay Area for the winter and are periodically spotted during the non-breeding season), such as Tree Swallow, followed by Violet-Green (mid-February), Cliff (mid-February), and Barn and Northern Rough-Winged (late February). Purple Martin will also arrive by April and nest in the area. Bank Swallow is rare to locally extinct in much of the Bay Area.

Ruby-crowned Kinglets: Small Is Beautiful

One of the most common birds you can see in the winter landscape now is the diminutive and frenetic Ruby-Crowned Kinglet. Enjoy them while they’re here. They’ll soon be gone. By the end of April, most have left for breeding grounds in the foothills/Sierras and latitudes farther north, and all vacate the Bay Area during the breeding season.

Meanwhile, populations of the look-alike Golden-Crowned Kinglet are also present in the Bay Area during this time, but it only breeds in the western portion of Marin County. One major telltale field mark clue is the absence of feather coloring in the crown of most Ruby-Crowneds, while all Golden-Crowned, both male and female, exhibit yellow in the crown (with the male also wearing a golden central median stripe on the crown).

Their feeding behavior is also often an easy way to tell them apart from a distance. One study suggests Ruby-Crowneds forage within the upper thirds of trees more frequently and that individuals typically hover while they feed in a tree’s interior portions. On the other hand, Golden-Crowned populations often use a gleaning behavior to find food resources at the tips of branches (Kathleen E. Franzreb, Foraging Habits of Ruby-Crowned and Golden-Crowned Kinglets in an Arizona Montane Forest,

Kathleen E. Franzreb. 139-145, 1984; A. Keast and S. Saunders, Ecomorphology of the North American Ruby-crowned (Regulus calendula) and Golden-crowned (R. satrapa) Kinglets. Auk 108: 880–888, 1991)

Owl All Around

Seeing an owl during the day in open country? If so, you may be observing the Short-Eared Owl, which wears a dark facial disk that emphasizes its yellow eyes. Short-eard Owl is rarely seen in Marin County, but individuals are sometimes spotted in isolated portions along Tomales Bay or in distant trails and raised embankments accessible from the Las Gallinas Ponds in San Rafael.

Other day-flying, or diurnal, owl species to look for include the Burrowing, Long-Eared and Barn Owl. Which is the most common owl species in our area? The answer is the Great Horned Owl, a species that is more common in urban-suburban areas than people realize. Even the slightest sliver of natural surroundings may attract this species that has evidently adapted well to living within and near developed areas.

The Burrowing Owl is rare and usually only seen in open areas during the non-breeding season. Long-Eared are also rare and perhaps best found in dense growths of vegetation such as riparian corridors. Barn Owl nests throughout the area, both in human structures or in trees such as oaks. More common, though heard more often than seen, is the diminutive Western Screech-owl, a forest dweller. Nest boxes often attract them, including one in both my front and backyard woodland.

Mammal Watch

Winter-active mammals you can spot at higher altitudes this time of year include pikas, deer mice, pocket gophers and tree squirrels. Other active foraging mammals to search for are meadow mice, mountain beaver (or Aplodontia), shrew, and porcupine.

March, 2024

Sky Watch*:

Go to: https://www.timeanddate.com/astronomy/night/

Then type in your location to view the March night sky scenario for your area.

(* = Enchanting views of my night sky in Novato, CA location enhanced thanks to optic devices from Out of This World Optics, a Mendocino, CA binocular and spotting scope storefront and mail order company you may enjoying discovering at OutofThisWorldOptics.com)

1) Moon & Planet Rise & Set Times

For The 1st of This Month (at Latitude: 38:03:38 N, Longitude: 122:32:27 W, which is Novato, CA, 20 miles north of San Francisco, CA in Marin County):

(Courtesy of almanac.com)

Planetrise/Planetset, Mon, Mar 4, 2024 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planet | Rise | Set | Meridian | Comment |

| Mercury | Sun 6:54 am | Sun 6:23 pm | Sun 12:38 pm | Very difficult to see |

| Venus | Mon 5:38 am | Mon 4:07 pm | Mon 10:52 am | Slightly difficult to see |

| Mars | Mon 5:24 am | Mon 3:39 pm | Mon 10:32 am | Slightly difficult to see |

| Jupiter | Sun 9:11 am | Sun 10:47 pm | Sun 3:59 pm | Fairly good visibility |

| Saturn | Mon 6:34 am | Mon 5:40 pm | Mon 12:07 pm | Extremely difficult to see |

| Uranus | Sun 9:31 am | Sun 11:27 pm | Sun 4:29 pm | Difficult to see |

| Neptune | Sun 7:16 am | Sun 7:06 pm | Sun 1:11 pm | Extremely difficult to see |

2) Planet Highlights: (courtesy of earthsky.com)

Visible planets in March 2024

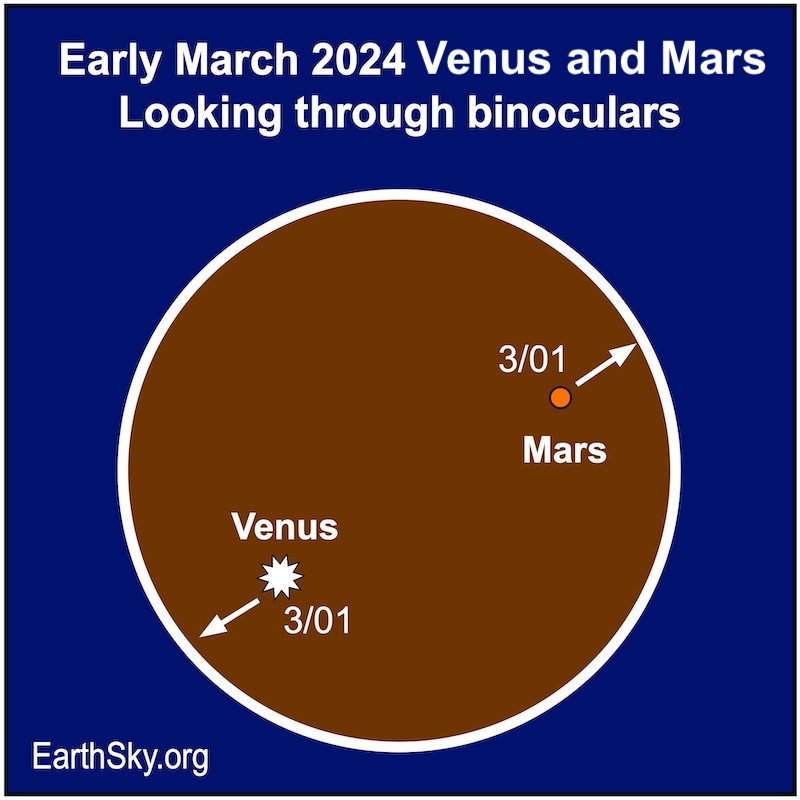

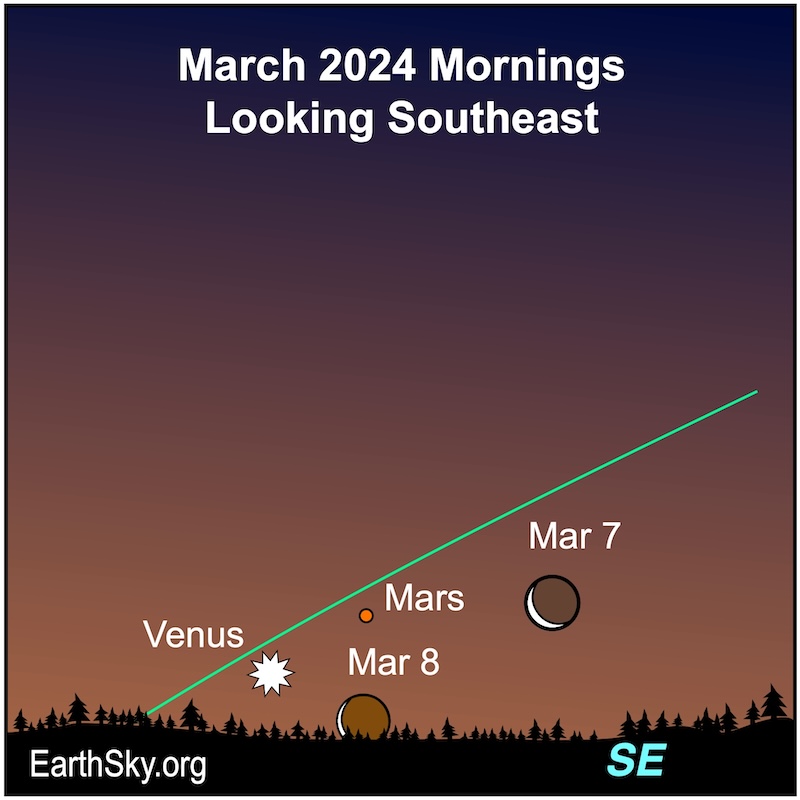

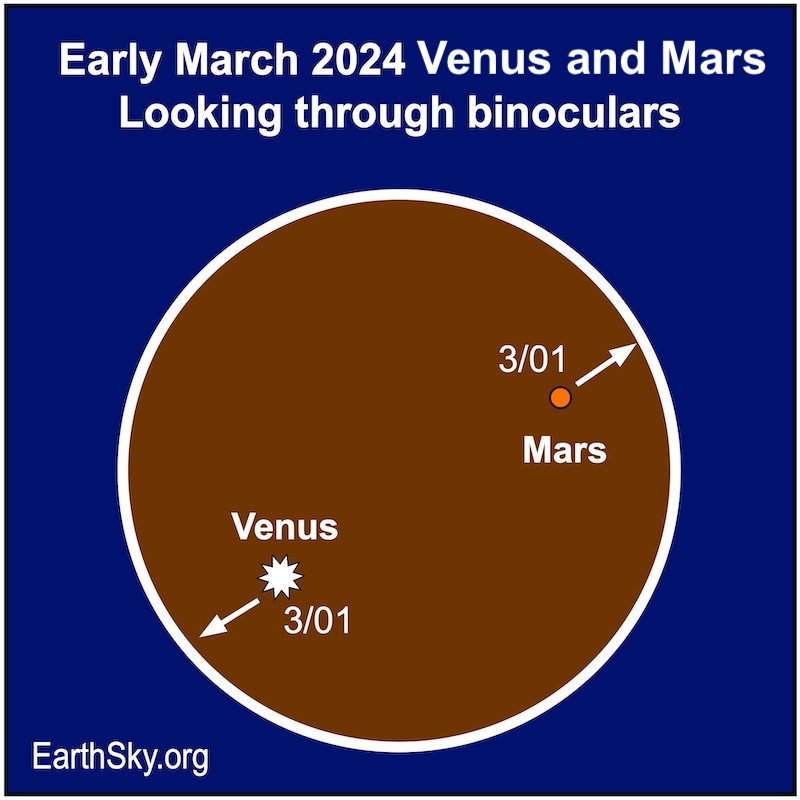

Early March mornings: Venus and Mars

The brightest planet is Venus, and at the beginning of March it will be low in the morning twilight descending more each day. At the same time, Mars climbs slowly higher each day but will remain challenging to spot in the morning twilight. It’ll be fun to watch them grow apart. Venus will disappear before mid-month. When is the last day you catch Venus in the sky? Once Venus slips away, it won’t be visible again until it pops up in the evening sky in August. Also, a thin waning crescent moon will visit Venus and Mars on the mornings of March 7 and 8, 2024. The pair will be easiest to spot in binoculars.

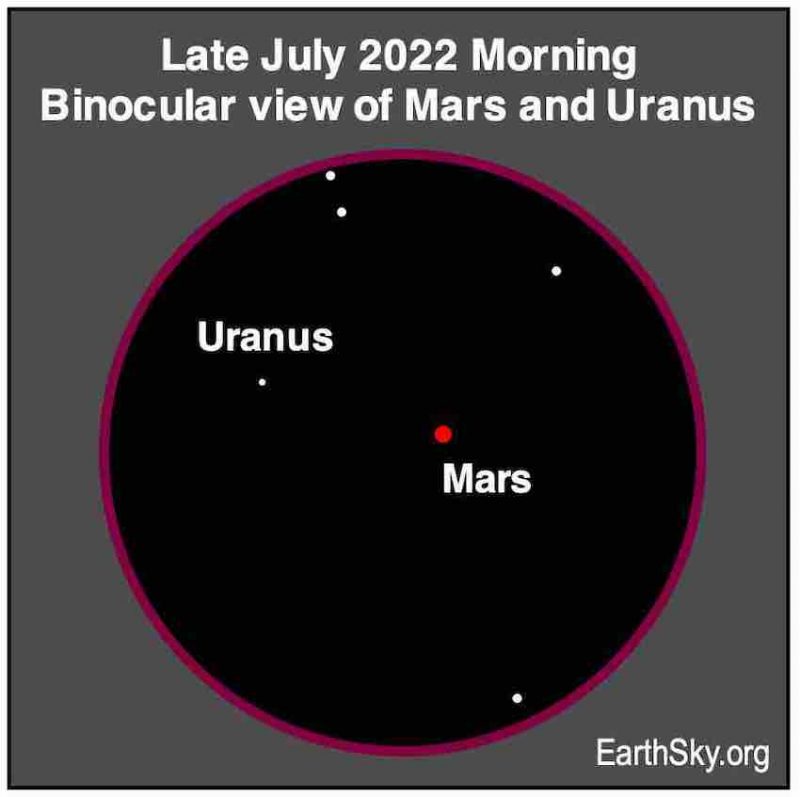

Here’s a binocular view of Venus and Mars as they move away from each other at the beginning of March.

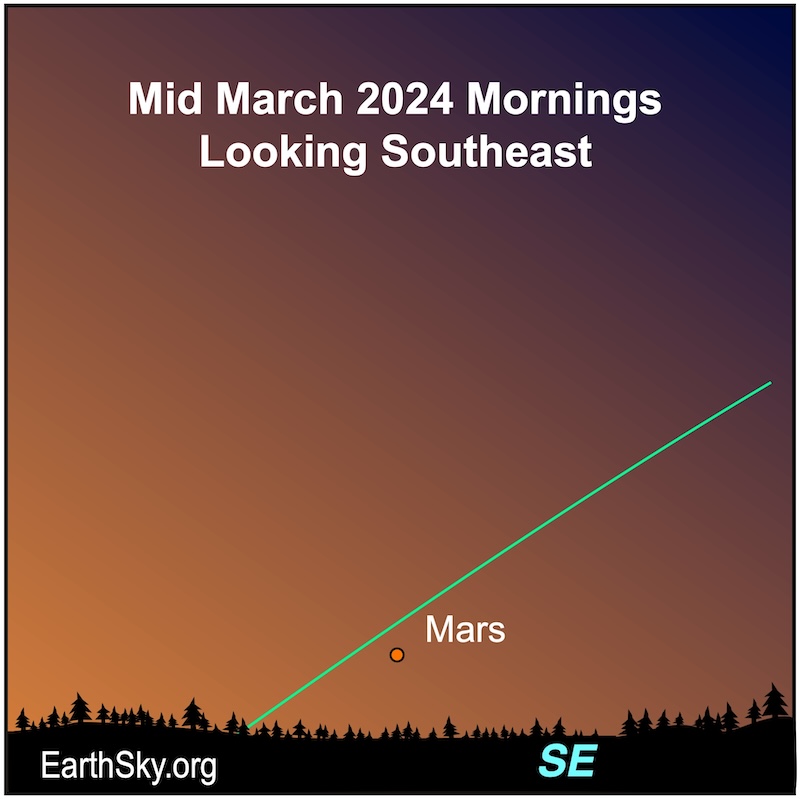

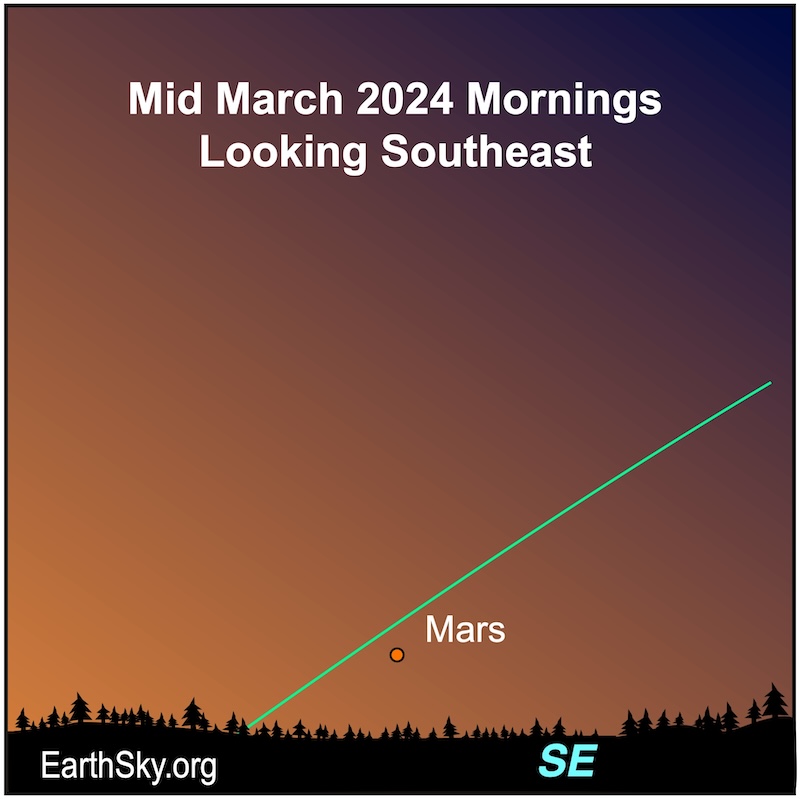

Mid-March mornings: Mars

Mars will become easier to identify in the morning twilight, rising about an hour before sunrise. Although you probably won’t see them in the morning twilight, Mars will lie in front of the constellation of Capricornus the Sea-goat and will move into Aquarius the Water Bearer near the end of the month. Mars remains a morning object through all of 2024.

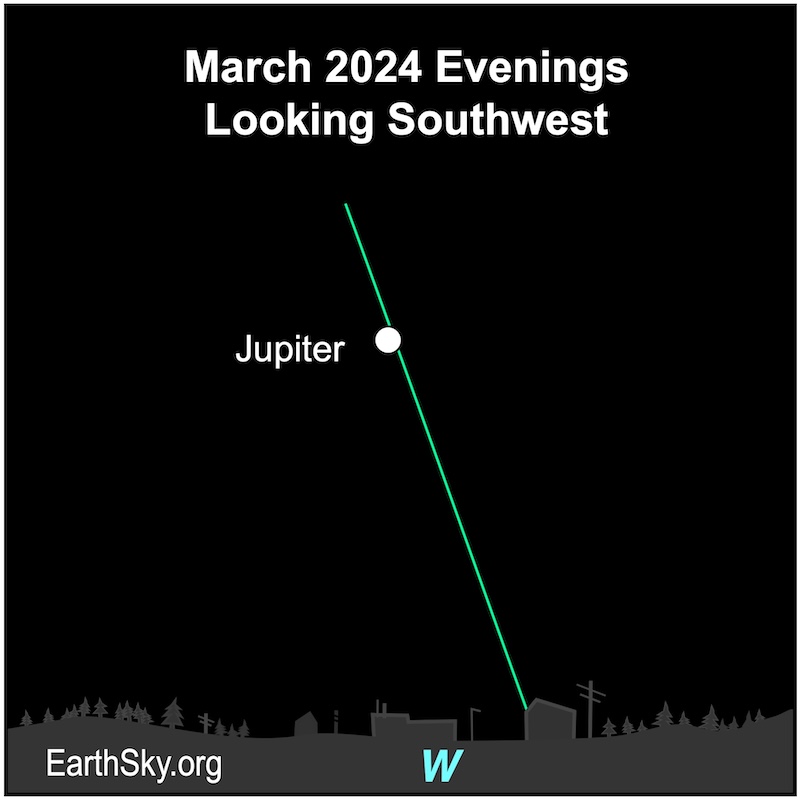

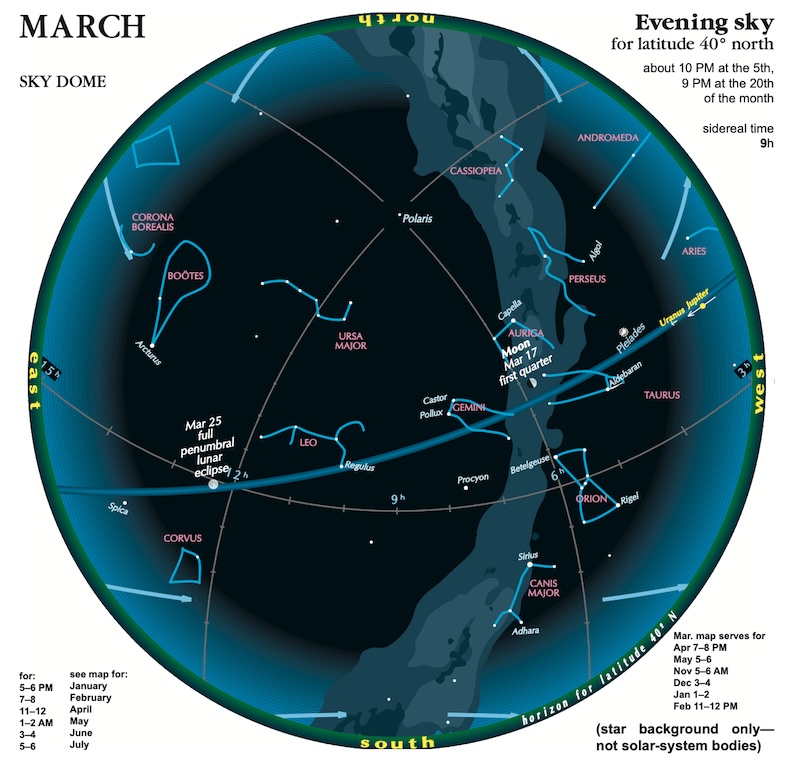

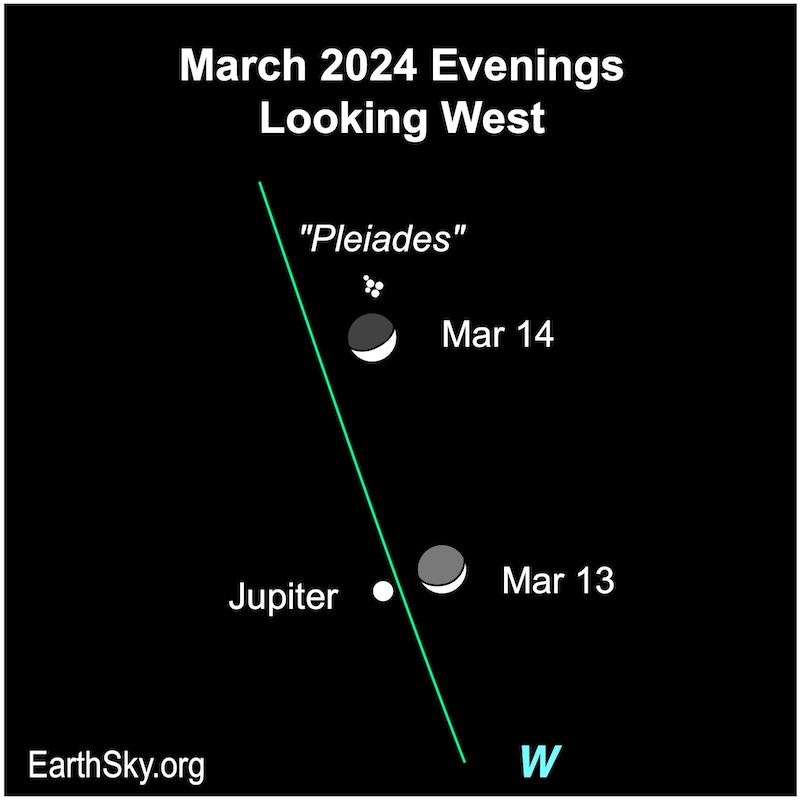

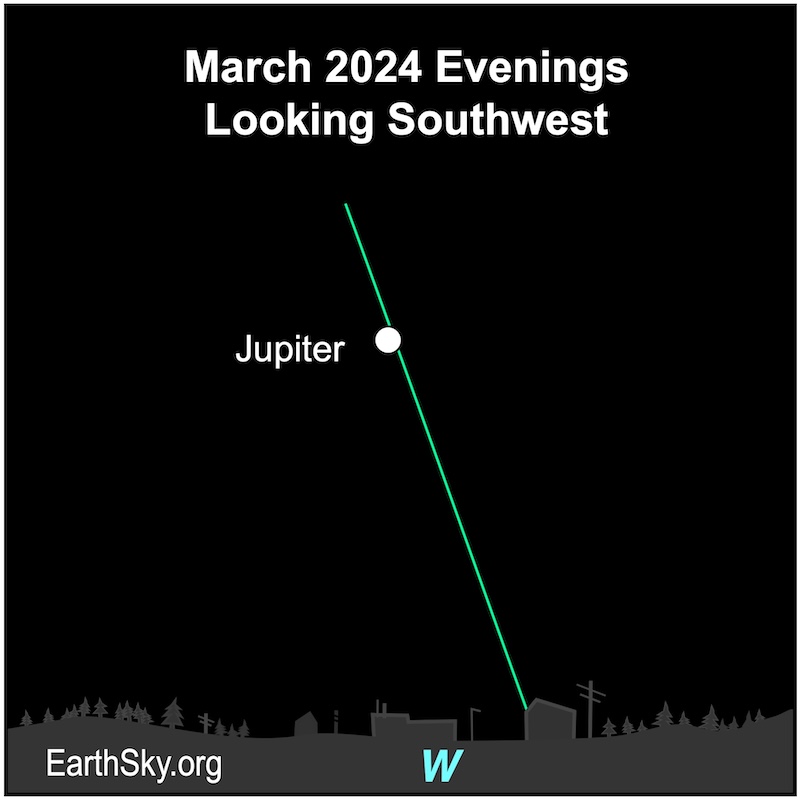

March evenings: Jupiter

Bright Jupiter is easy to spot in the March 2024 evening sky. However, it is losing altitude and brightness as it descends closer to the sun. It will set about five hours after the sun at the beginning of the month, and about three hours after sunset by month’s end. It will shine near the pretty Pleiades star cluster in the constellation Taurus the Bull. Jupiter reached opposition overnight on November 2-3, 2023, when we flew between it and the sun. So, as Jupiter recedes from Earth, it’ll fade a bit in our sky. It will reach opposition again on December 7, 2024, so it’ll be at its brightest for the year around then. It will lie in the dim constellation Aries the Ram, and it’ll shine at -2.1 magnitude by month’s end. The waxing crescent moon will float by Jupiter on March 13, 2024.

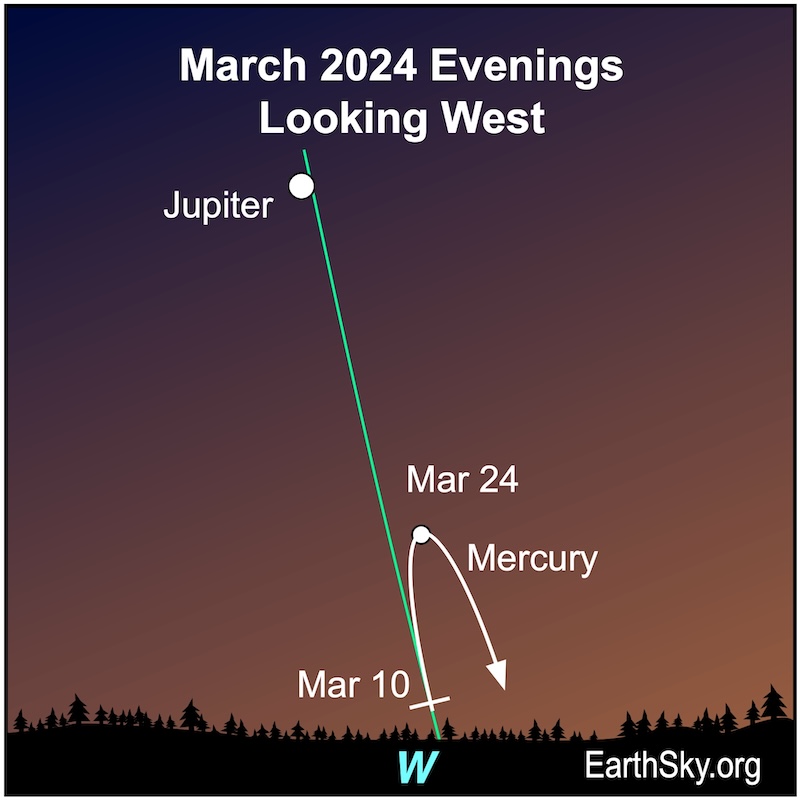

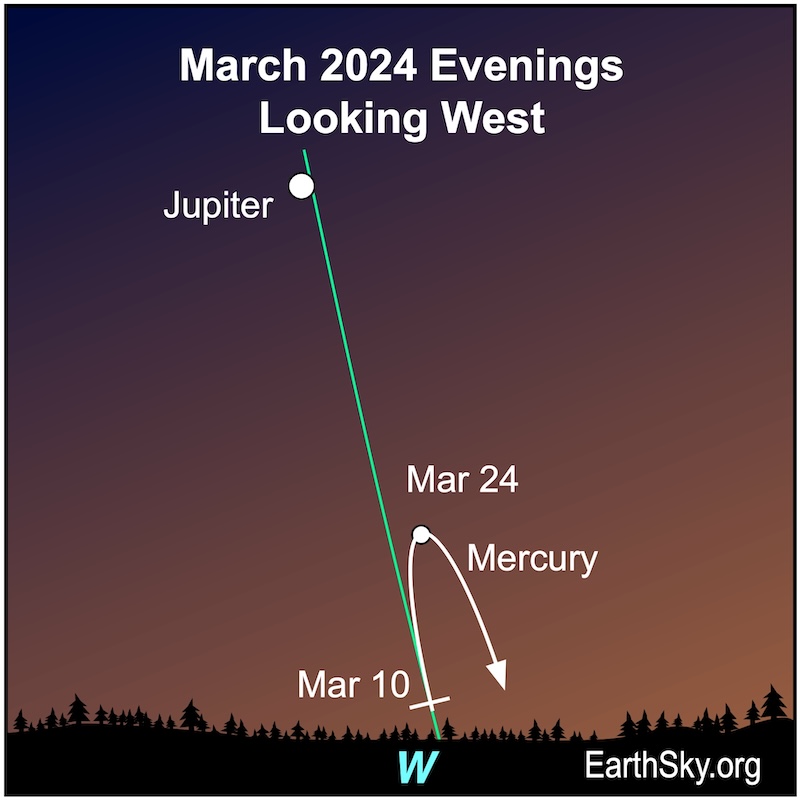

March evenings: Mercury

The bright but elusive planet Mercury emerges during the second week of the month and quickly rises to prominence after sunset. This will be Mercury’s best evening apparition for the Northern Hemisphere in 2024. It’ll reach its greatest distance from the sun on the evening of March 24. And then, it’ll fade quickly and be gone by the end of the month. Bright Jupiter will be higher in the sky.

Where’s Saturn?

You probably won’t see Saturn this month.

Thank you to all who submit images to EarthSky Community Photos! View community photos here. We love you all. Submit your photo here.

Looking for a dark sky? Check out EarthSky’s Best Places to Stargaze.

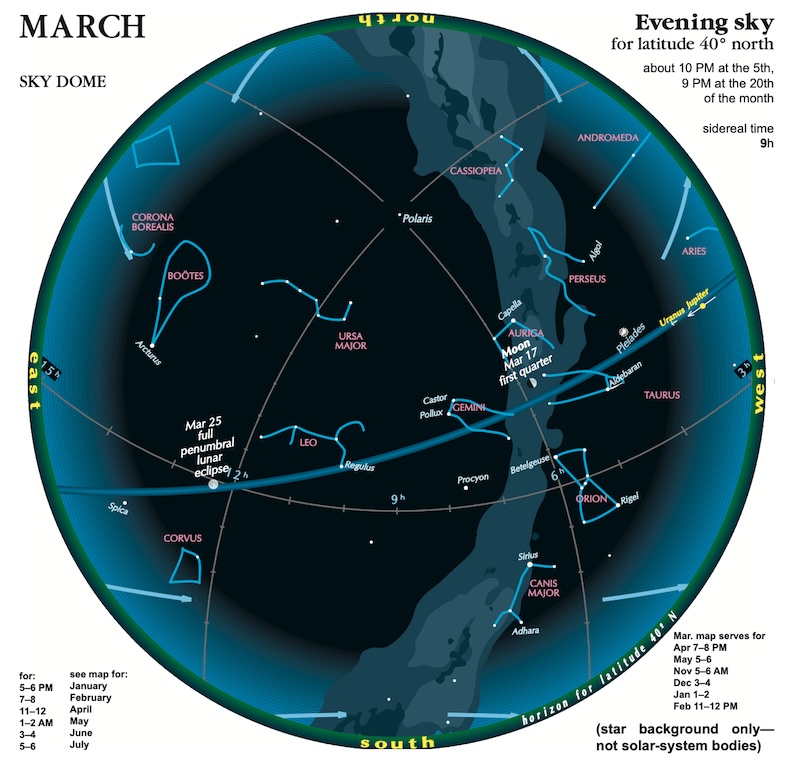

Sky dome maps for visible planets and night sky

The sky dome maps come from master astronomy chart-maker Guy Ottewell. You’ll find charts like these for every month of 2024 in his Astronomical Calendar.

Guy Ottewell explains sky dome maps

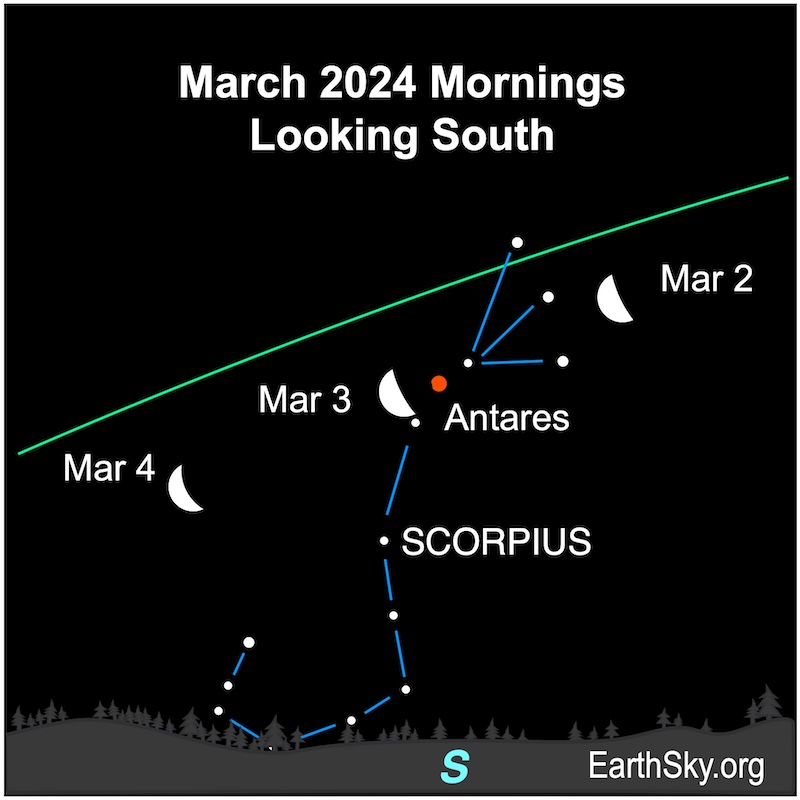

Morning of March 4: Moon near Antares

On the morning of March 4, 2024, the waning crescent moon – barely past last quarter – appears lower in the sky than Antares, the Scorpion’s Heart. The moon rises in the wee hours of the morning and sets about noon.

Our charts are mostly set for the northern half of Earth. To see a precise view – and time – from your location, try Stellarium Online.

March evenings: Watch for the zodiacal light

The zodiacal light – a hazy pyramid of light, really sunlight reflecting off dusk grains that move in the plane of our solar system – is now visible after evening twilight for Northern Hemisphere observers with dark skies. Southern Hemisphere observers? Look for it before morning twilight begins. Read about the zodiacal light.

Moon phases for the month

Join EarthSky’s Marcy Curran for a 1-minute video preview of the moon phases – and dates when the moon visits some planets – for the month of March 2024.

35 days from eclipse day: Good sun? Or bad sun?

Today we’re 35 days out from the April 8 total solar eclipse! For much of human history, total solar eclipses were seen as bad omens. But some traditional cultures see solar eclipses in an entirely different light. Join Cristina Ortiz as she explores “good” suns – and “bad” suns – in stories from around the world.

Visit the Countdown to Eclipse video series

Read about the April 8 total solar eclipse.

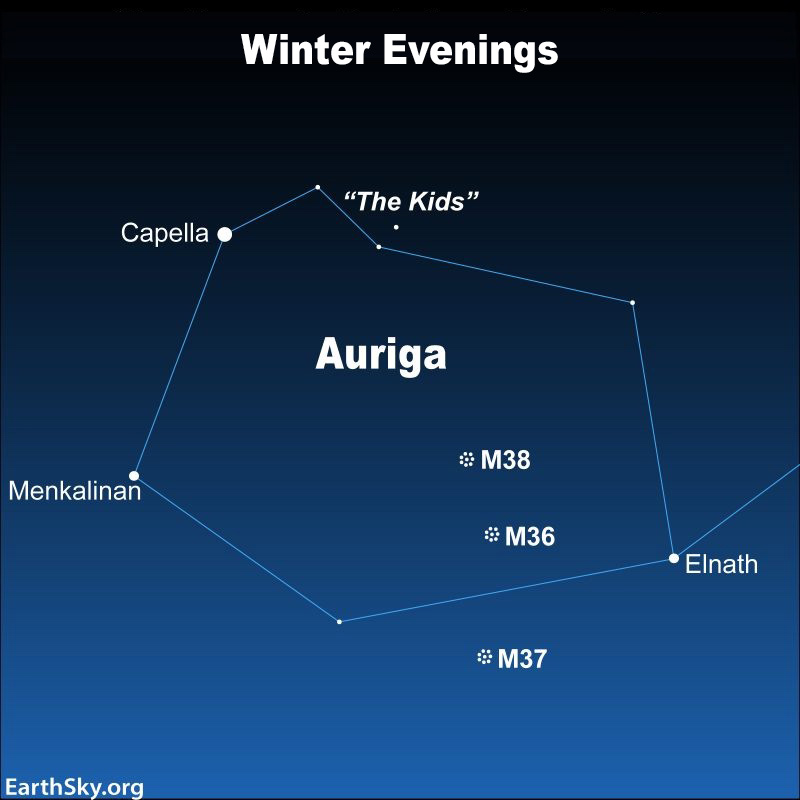

March evenings: Look for Auriga the Charioteer

The bright star Capella is almost overhead this month. It’s the brightest light in the constellation Auriga the Charioteer. To be sure you’ve found Capella, look for a little triangle of stars nearby. Capella is sometimes called the Goat Star, and the little triangle of stars is an asterism called The Kids. After finding Capella, you can trace out the rest of this pentagon-shaped group of stars. Read more about Capella and Auriga.

March 7 and 8 mornings: Moon near Venus and Mars

In the morning twilight of March 7 and 8, 2024, the slender waning crescent moon will float near bright Venus and a much dimmer Mars. On March 7, the lit portion of the moon will point toward the two planets. On the morning of March 8, the trio forms a triangle low on the horizon. Binoculars might help locate them about 30 to 40 minutes before sunrise.

Daylight saving time begins March 10

For those observing daylight saving time, set your clocks forward 1 hour.

March 10: New moon

The instant of new moon will fall at 9 UTC (4 a.m. CDT) on March 10, 2024. It’s a perfect time for stargazing under dark skies. The new moon rises and sets with the sun. This is the 3rd new supermoon of 2024 and the 3rd of five new supermoons in a row. It’s 221,767 miles (356,900 km) away from Earth.

March 10: Moon reaches perigee

The moon will reach perigee – its closest point in its elliptical orbit around Earth – at 7 UTC (1 a.m. CDT) on March 10, 2024, when it’s 221,763 miles (356,893 km) away. High tides are possible.

Our charts are mostly set for the northern half of Earth. To see a precise view – and time – from your location, try Stellarium Online.

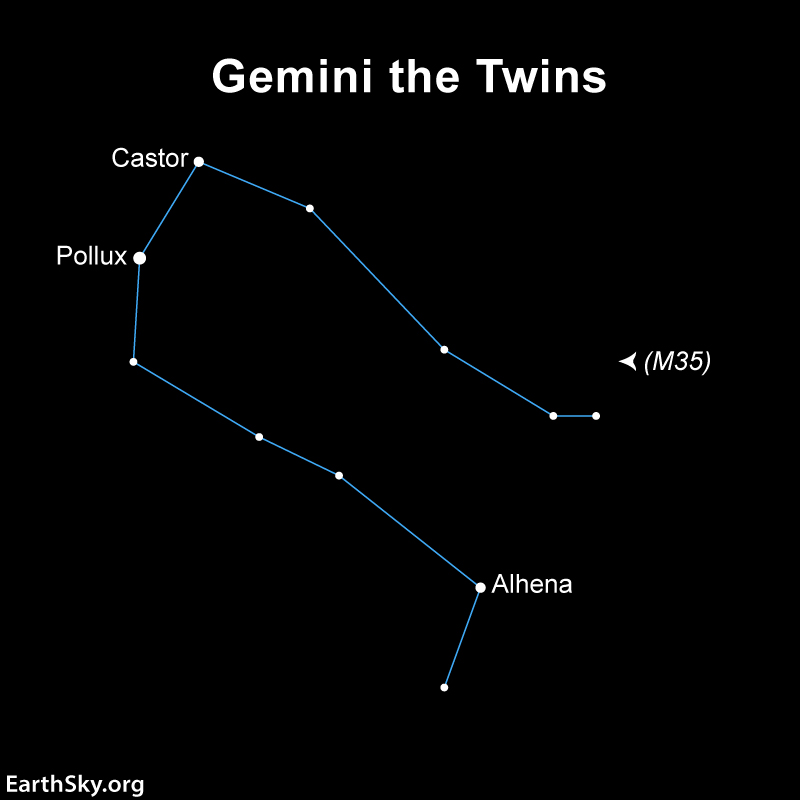

March evenings: Look for Gemini the Twins

On March evenings, the constellation Gemini the Twins is high overhead on the sky’s dome. Look for the bright – and obvious – “twin” stars, Castor and Pollux. These two stars aren’t really twins. Pollux is brighter and more golden. Castor is slightly fainter and white. But both stars are bright, and they’re noticeable for being close together on the sky’s dome. You may need dark skies to locate the rest of the constellation. In March, the constellation is highest around 9 p.m. That’s your local time, no matter where you are on the globe. You can use binoculars to see a nice open star cluster listed on the chart below, M35.

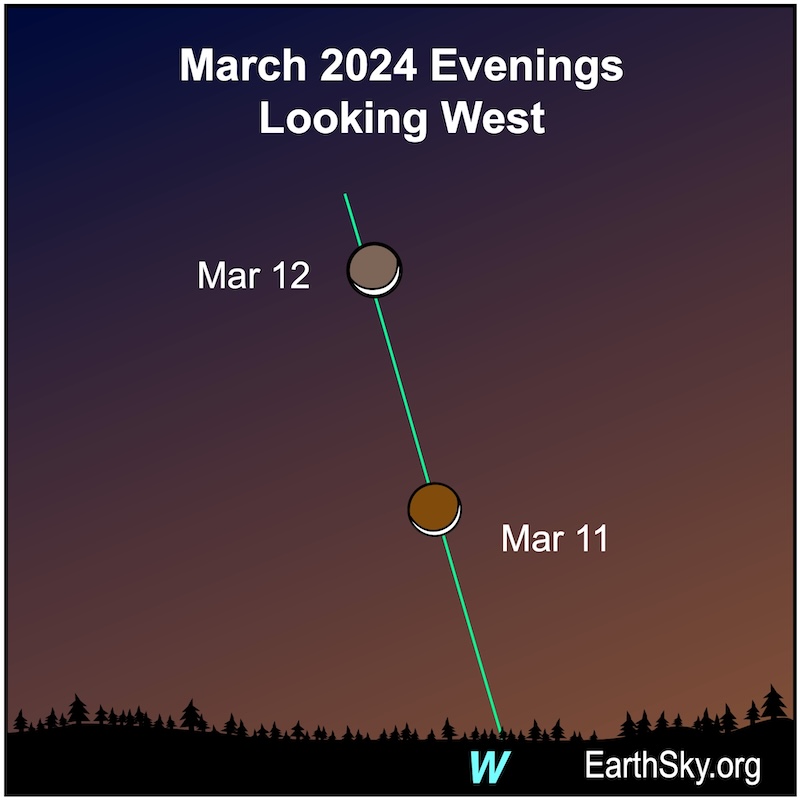

March 11 and 12 evenings: Thin crescent moon

The thin waxing crescent moon will hang in the western twilight on the evenings of March 11 and 12, 2024. Do you notice a lovely glow on the unlit side of the moon? That’s earthshine! It’s reflected light from the Earth.

March 13 and 14 evenings: Moon near Jupiter and the Pleiades

On the evenings of March 13 and 14, 2024, the waxing crescent moon will glow near the bright planet Jupiter. The moon and Jupiter will set around midnight. You will also see the tiny dipper-shaped Pleiades star cluster, or Seven Sisters, nearby. The moon will lie especially close to the Pleiades on March 14. They’ll set around midnight.

Our charts are mostly set for the northern half of Earth. To see a precise view – and time – from your location, try Stellarium Online.

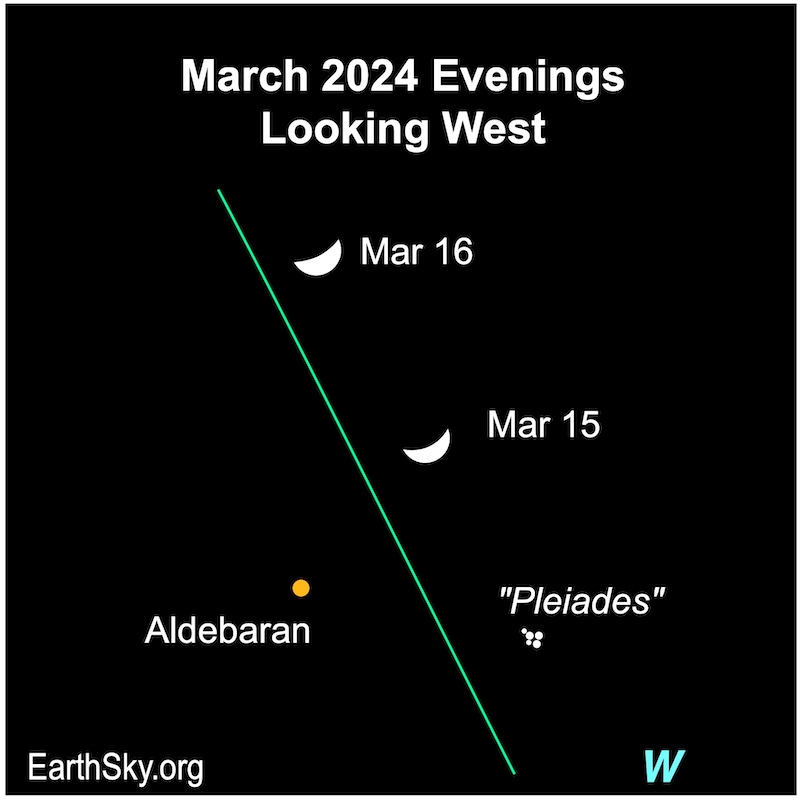

March 15 and 16 evenings: Moon near Aldebaran and Pleiades

The thick waxing crescent moon will lie near the Pleiades star cluster on the evenings of March 15 and 16, 2024. The Pleiades is also known as the Seven Sisters, or Messier 45. It appears as a glittering, bluish cluster of stars in the constellation Taurus the Bull. Meanwhile, what is that fiery orange star nearby? It’s Aldebaran, Eye of the Bull in Taurus. The moon, Pleiades and Aldebaran will cross the sky together and set after midnight.

March 17: 1st quarter moon

The instant of 1st quarter moon will fall at 4:11 UTC on March 17, 2024 (10:11 p.m. CDT on March 16). A 1st quarter moon rises around noon your local time and sets around midnight. Watch for it high in the sky at sundown.

Our charts are mostly set for the northern half of Earth. To see a precise view – and time – from your location, try Stellarium Online.

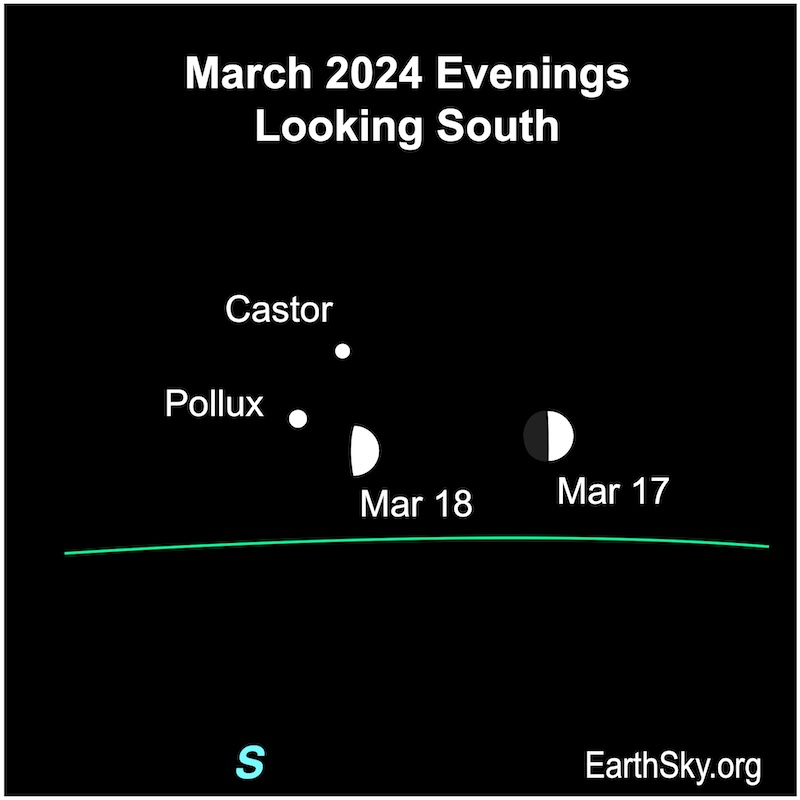

March 17 and 18 evenings: Moon near Pollux and Castor

On the evenings of March 17 and 18, 2024, the bright waxing gibbous moon will pass Pollux and Castor, the “twin” stars of Gemini. They’re named for twin brothers born from different fathers. So, they don’t really look alike. Pollux is a bit brighter and golden in color. And Castor appears white. They’ll rise before sunset and travel across the sky’s dome until a little before sunrise.

March 20: March Equinox

The March equinox marks the sun’s crossing above the Earth’s equator, moving from south to north. It’ll happen at 3:06 UTC on March 20, 2024 (9:06 p.m. CDT on March 19). It marks the beginning of spring in the Northern Hemisphere and autumn in the Southern Hemisphere.

Our charts are mostly set for the northern half of Earth. To see a precise view – and time – from your location, try Stellarium Online.

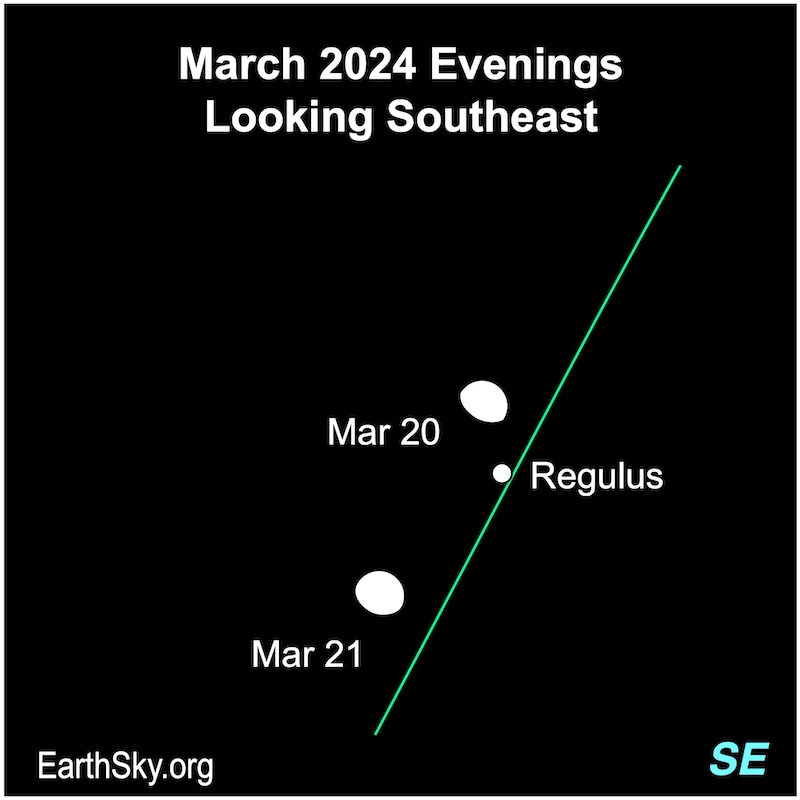

March 20 and 21 evenings: Moon near Regulus

On the evenings of March 22 and 23, 2024, the fat waxing gibbous moon will float near the bright star Regulus, the brightest star in Leo the Lion. They’ll be visible through dawn.

Moon at apogee March 23

The moon will reach apogee – its farthest distance from Earth in its elliptical orbit around Earth – at 16 UTC (10 a.m. CDT) on March 23, 2024, when it’s 252,459 miles (406,293 km) away.

March 24 and 25: Full Worm Moon and penumbral lunar eclipse

The instant of full moon – the Worm Moon – will fall at 7 UTC (1 a.m. CDT) on March 25, 2024. It’ll be the second smallest – most distant – full moon in 2024 at 251,900 miles (405,394 km) away. Also, if the moon is above the horizon, you can see a penumbral lunar eclipse. People in parts of Antarctica, the western half of Africa, western Europe, the Atlantic Ocean, the Americas, the Pacific Ocean, Japan and the eastern half of Australia will see a deep penumbral lunar eclipse. The penumbral eclipse begins at 4:53 UTC on March 25, 2024 (10:53 p.m. CDT on March 24).

March 24 evening: Mercury at greatest evening elongation

Mercury is farthest from the sun on our sky’s dome – at greatest elongation – at 23 UTC on March 24, 2024 (5 p.m. CDT). At that time, Mercury is 19 degrees from the sun in our sky. This will be its best evening apparition of 2024 for the Northern Hemisphere.

Our charts are mostly set for the northern half of Earth. To see a precise view – and time – from your location, try Stellarium Online.

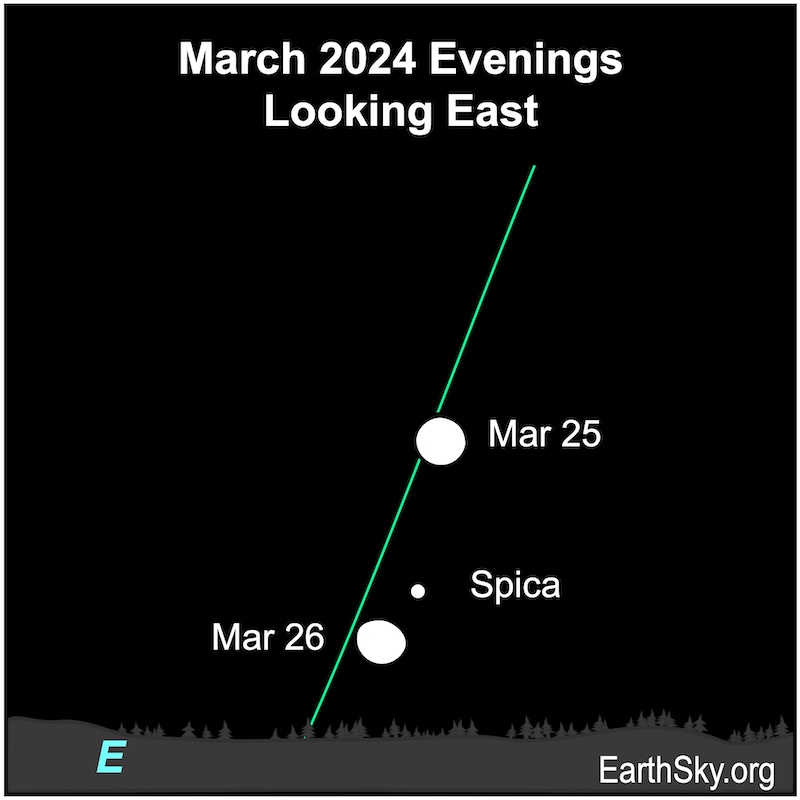

March 25 and 26 evenings: Moon near Spica

On the evenings of March 25 and 26, 2024, the waning gibbous moon will hang near the bright star Spica in Virgo the Maiden. They’ll rise soon after sunset and be visible until sunrise.

March 27 to April 10: Zodiacal light

The zodiacal light may be visible after evening twilight for Northern Hemisphere observers for the next two weeks. Southern Hemisphere observers? Look for it before morning twilight begins.

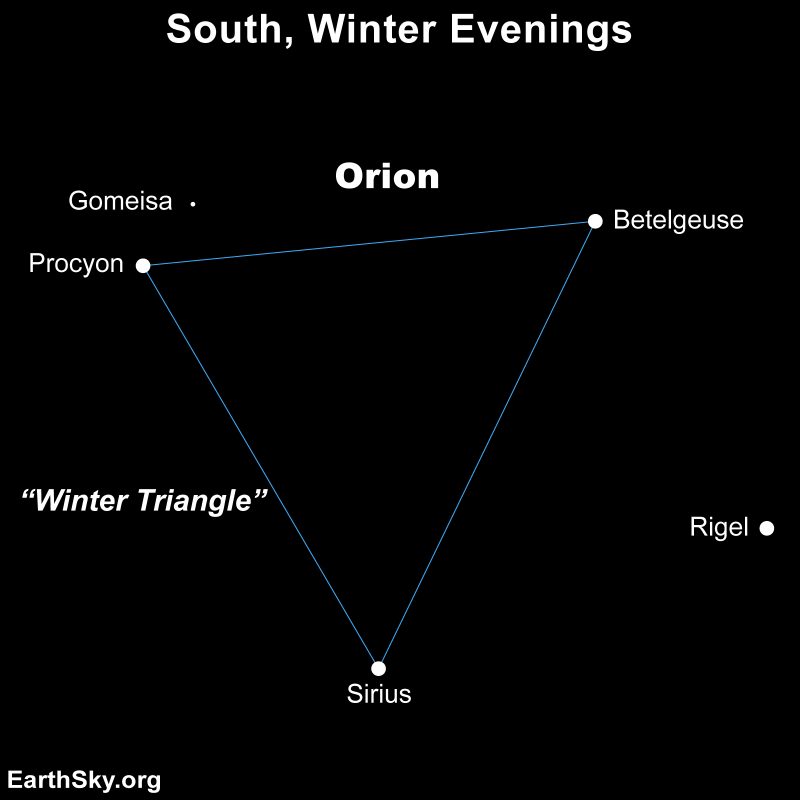

March evenings: Look for the Winter Triangle

The Winter Triangle isn’t a constellation. It’s an asterism, made of three bright stars in the Northern Hemisphere’s winter sky (or the Southern Hemisphere’s summer sky). Procyon, Sirius and Betelgeuse are easy to find on winter and spring evenings. It’s also part of a larger asterism, the Winter Circle. And locating bright stars can help you find constellations. Sirius is in Canis Major, Procyon is in Canis Minor and Betelgeuse is in Orion the Hunter.

Our charts are mostly set for the northern half of Earth. To see a precise view – and time – from your location, try Stellarium Online.

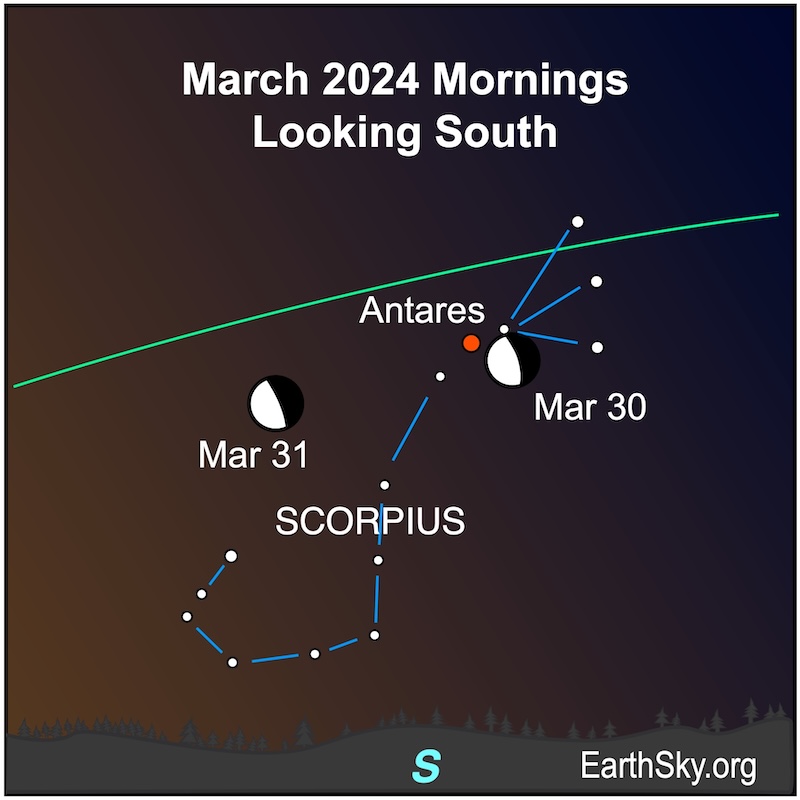

March 30 and 31 mornings: Moon near Antares

On the mornings of March 30 and 31, 2024, the waning gibbous moon will lie close to the bright star Antares in Scorpius the Scorpion. In fact, at 15 UTC on March 30, 2024, skywatchers in parts of northeast Melanesia, Micronesia and most of Polynesia will see the moon pass in front of – or occult – Antares.

Visible planets in March 2024

Early March mornings: Venus and Mars

The brightest planet is Venus, and at the beginning of March it will be low in the morning twilight descending more each day. At the same time, Mars climbs slowly higher each day but will remain challenging to spot in the morning twilight. It’ll be fun to watch them grow apart. Venus will disappear before mid-month. When is the last day you catch Venus in the sky? Once Venus slips away, it won’t be visible again until it pops up in the evening sky in August. Also, a thin waning crescent moon will visit Venus and Mars on the mornings of March 7 and 8, 2024. The pair will be easiest to spot in binoculars.

Here’s a binocular view of Venus and Mars as they move away from each other at the beginning of March.

Mid-March mornings: Mars

Mars will become easier to identify in the morning twilight, rising about an hour before sunrise. Although you probably won’t see them in the morning twilight, Mars will lie in front of the constellation of Capricornus the Sea-goat and will move into Aquarius the Water Bearer near the end of the month. Mars remains a morning object through all of 2024.

March evenings: Jupiter

Bright Jupiter is easy to spot in the March 2024 evening sky. However, it is losing altitude and brightness as it descends closer to the sun. It will set about five hours after the sun at the beginning of the month, and about three hours after sunset by month’s end. It will shine near the pretty Pleiades star cluster in the constellation Taurus the Bull. Jupiter reached opposition overnight on November 2-3, 2023, when we flew between it and the sun. So, as Jupiter recedes from Earth, it’ll fade a bit in our sky. It will reach opposition again on December 7, 2024, so it’ll be at its brightest for the year around then. It will lie in the dim constellation Aries the Ram, and it’ll shine at -2.1 magnitude by month’s end. The waxing crescent moon will float by Jupiter on March 13, 2024.

March evenings: Mercury

The bright but elusive planet Mercury emerges during the second week of the month and quickly rises to prominence after sunset. This will be Mercury’s best evening apparition for the Northern Hemisphere in 2024. It’ll reach its greatest distance from the sun on the evening of March 24. And then, it’ll fade quickly and be gone by the end of the month. Bright Jupiter will be higher in the sky.

Where’s Saturn?

You probably won’t see Saturn this month.

Thank you to all who submit images to EarthSky Community Photos! View community photos here. We love you all. Submit your photo here.

Looking for a dark sky? Check out EarthSky’s Best Places to Stargaze.

Sky dome maps for visible planets and night sky

The sky dome maps come from master astronomy chart-maker Guy Ottewell. You’ll find charts like these for every month of 2024 in his Astronomical Calendar.

Guy Ottewell explains sky dome maps

Premiere Showing: Harbor Seal Pups Spotted On Shore

In California, March marks the beginning of pupping season for Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina). Females gather on shore in rookeries and give birth to a single 30-pound pup, which can swim shortly after birth.

Mothers may leave their pups alone on the rocks for briefly while they hunt for fish, squid and other seafood. Each year, well-intentioned, but misinformed people pick up or otherwise interfere with an “orphaned” seal. In turn, the pup (that waits patiently while its mother forages for their food before she returns) gets separated, then unknowingly absconded by an oblivious person.

Look for Harbor Seal rookeries in Bolinas Lagoon (Marin Co.) and Fitzgerald Marine Reserve (San Mateo Co.). Don’t approach too closely to the seals (especially if you are walking a dog) as you may disrupt their nursing or resting schedules.

Native Bees Prowling for Pollen (And Nectar)

Quick: what do you picture when you hear the word “Bee”? You probably think of Apis mellifera, the European Honeybee. But California has more than 1,500 species of its own native bees. Their sizes and colors are as varied as the plants on which they feed.

Native bees have evolved to hatch or come out of hibernation when their preferred food source is available. In spring, metallic green or blue bees in the genus Osmia and black bees of the genus Adrena appear in time to exploit early blooming flowers such as the California Poppy. Native bumblebees (genus Bombus) also make their debut early in the season — and you see them now as the largest bumblebees hovering close to the ground.

As the seasons change, so do the bee species and their preferred pollen and nectar plants. Wish to help native bees thrive? One way is to plant a variety of their favored flowering plants in your garden.

Professor Gordon Frankie and his students at the University of California –Berkeley have created a wonderful website filled with information about urban bee gardens: nature.berkeley.edu/urbanbeegardens/index.html

Seasonal Vernal Pools Shelter Vulnerable Species

Weeks and weeks of rain. Then months and months of dry, sunny weather. That’s California’s Mediterranean climate.

More exact, during the rainy season (typically November through March), where rain collects in grassland depressions (where impermeable layers of hardpan, claypan, or volcanic basalt occur) vernal pools form (i.e., temporary ponds). They may dry up and refill several times each rainy season.

Turns out the borders of these vernal pools host impressive colorful expressions of diverse wildflowers. In so doing, you’ll see rainbow-like concentric circles of vernal pool endemic wildflowers grow on the outer edges of pools. In turn, as water slowly evaporates as spring progresses, other flower species bloom as spring proceeds in relation to slowly-waning soil moisture.

Vernal pool wildflowers have descriptive names — Meadow Foam. Wooly Marbles, Button Celery, Butter and Eggs, to name just five. Joining them, invertebrates in impressive numbers occur in vernal pools. They provide food for birds, lizards, and other animals. These fragile habitats provide home to vulnerable, threatened, and endangered animals including the California Tiger Salamander, the Western Spadefoot Toad, and several species of fairy shrimp.

Habitat loss is one of the biggest threats to native species, and vernal pools are themselves threatened by development. Today, only 13% of California’s vernal pools remain. Most of the best-preserved pools are privately owned by conservation organizations or land trusts.

In Northern California, both Jepson Prairie Preserve in Solano County and Mather Field in Sacramento County offer guided tours of their vernal pools in spring. For more information, visit http://www.vernalpools.org

Baby Time

Which animals give birth this month? A large variety. Watch for baby Western Tree Squirrels, Opossum, and Raccoons. We don’t usually get lucky enough to see newborn mammals because the mother or both parents typically hide their young from any potential predators. But you can sometimes see Western Tree Squirrel mothers transferring their babies from one tree “nest” to another or spot a family of Raccoons at night in your backyard (perhaps easiest accomplished while using an infrared light bulb to cast a glow that Raccoons ignore, but is bright enough for your own viewing pleasure).

For another notable exception, see the entry above about Harbor Seals.

Western Tree Squirrel: Newborns All Around

Even urban areas with sparse tree growth may host Western Tree Squirrel populations. Now’s an ideal time to see males competing for the attention of females. Two to five young are born this month where females have retreated to tree cavities. By June, the newborns are active (though not yet full grown, so you can tell them apart from adults).

They’re Back: Returning Migrants

During most breeding seasons, you can expect this month to feature a variety of migrating birds returning to coastal northern California in good numbers, including the House Wren, Warbling Vireo, Wilson’s Warbler, Pacific-Slope Flycatcher and Cliff Swallow.

Rare Bird Alert Hotline

Do you wish to see rare, accidental or early bird migrants in northern California? Call the “Bird Box” to find out at 415/681-7422. You may also record your own bird sighting reports at the same phone number.

Fluttering By: Butterflies and Moths

Now’s the time to watch for the appearance of various butterflies and moths. One of the most appealing is the Silkmoth (Saturnia mendocino), which wears a striking black-rimmed eyespot on each wing. Look for them most commonly in coastal and mountain chaparral.

Mountain Lookout: Birds Up High

Going to the California mountains this time of year? Be on the lookout for several species of birds: Williamson’s Sapsucker (a woodpecker that feeds on the sap of lodgepole pine during the summer but eats more insects in the winter), Black-backed Woodpecker, Mountain Chickadee (that eats larvae of the lodgepole needleminer during the winter), Pine Grosbeak (less common in winter up high), Red-breasted Nuthatch, and Red Crossbill (also less common). The latter two species are year-round residents in Marin County, but they are never common to see, and are often detected initially by a birder’s ear tuned to the landscape.

Bon Voyage: Winter Resident Migration

Some winter resident birds in the Bay Area and northern California begin to leave now for breeding areas elsewhere, including species such as American Pipit and Cedar Waxwing.

Wake Up Call: Awakening From Hibernation

Which true hibernating mammals are getting closer to “waking up” from their long winter’s sleep? In foothill and mountainous areas of northern California, yellowbelly marmot, least chipmunk, California ground squirrel, and western jumping mice all hibernate. Some of these species may spend seven to eight months in a torpid state, though not all ground squirrel populations hibernate and many individuals in our area remain above ground or are active by January.

The Numbers Are In: Returning Bird Migrants

Migrating birds whose return to northern California typically occurs in higher numbers now (and into the first two weeks of April) include MacGillivray’s Warbler, Black-headed Grosbeak, Yellow Warbler, Olive-sided Flycatcher, Lazuli Bunting, and Swainson’s Thrush. Excellent guides to birding in our area include “Birder’s Guide to Northern California” (Lolo and Jim Westrich, Gulf Publishing Co., 1991) and “Birding Northern Calfornia,” John Kemper, A Falcon Guide, Globe Pequot Press, 2001). You may also wish to find guided birding walks that are pre-scheduled on local Audubon chapter web sites that are accessed through http://www.audubon.org

(Click on the home page’s button titled “states and chapters” to access any local California Audubon chapter among the dozens listed.)

April, 2023

Sky Watch*:

This Week’s Sky at a Glance, April 14 – 23, 2023

Venus shines with Aldebaran and the Pleiades in late twilight. After sunset on the 20th, try to spot your record-breaking thinnest young Moon. And Leo walks west with a mouse-galaxy dangling from his chin.

(* = Enchanting views of my night sky in Novato, CA location are enhanced thanks to optic devices from Out of This World Optics, a Mendocino, CA binocular and spotting scope storefront and mail order company you may enjoying visiting at OutofThisWorldOptics.com)

Planets To See In April: (Courtesy of skyandtelescope.com)

Mercury is fading fast in the western twilight: from a modest magnitude +0.6 on Friday April 14th to an invisible (in the low twilight) +2.3 a week later. Early this week, use binoculars to help hunt for Mercury about two fists at arm’s length to the lower right of Venus.

Venus (magnitude –4.1, in Taurus) is the brilliant “Evening Star” in the west during and after dusk. It doesn’t set until two hours after full darkness. In a telescope Venus is a dazzling little gibbous globe (72% sunlit) 15 or 16 arcseconds in diameter. It’s gradually enlarging and waning in phase. It’ll be 50% lit by late May and a dramatic crescent from mid-June through mid-July.

Mars is crossing Gemini. Look for it high in the west in early evening, lower in the west later. It’s upper left of Venus by three or four fists at arm’s length, and below Pollux and Castor.

Mars has faded to magnitude +1.2, the same brightness as modest Pollux above it. But Mars shows a deeper orange tint.

Mars is nearly on the far side of its orbit from us, so in a telescope it’s just a tiny blob 5½ arcseconds wide.

Moon & Planet Rise & Set Times*

* = Courtesy of timeanddate.com/astronomy/night/

Note: To see your area’s rise and set planet times, visit https://www.almanac.com/astronomy/planets-rise-and-set. Then, type in your city, state and zip code to see the results like mine below for 4/15/23 (at Latitude: 38:03:38 N, Longitude: 122:32:27 W, which is Novato, CA, 20 miles north of San Francisco, CA in Marin County):

| Planetrise/Planetset, Fri, Apr 15, 2023 |

|---|

| Body | Rises | Crosses Meridian |

Illum. | Sets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 7:13 A.M. NE |

2:18 P.M. 70° |

28% | 9:23 P.M. NW |

| Venus | 8:27 A.M. NE |

3:48 P.M. 74° |

72% | 11:09 P.M. NW |

| Mars | 10:55 A.M. NE |

6:23 P.M. 76° |

91% | 1:53 A.M. NW |

| Jupiter | 6:34 A.M. E |

1:01 P.M. 59° |

100% | 7:28 P.M. W |

| Saturn | 4:36 A.M. E |

10:02 A.M. 40° |

100% | 3:28 P.M. W |

| Uranus | 7:39 A.M. E |

2:36 P.M. 68° |

100% | 9:32 P.M. W |

| Neptune | 5:30 A.M. E |

11:24 A.M. 49° |

100% | 5:18 P.M. W |

| Pluto | 3:02 A.M. SE |

7:48 A.M. 29° |

100% | 12:35 P.M. SW |

| Planet | Rise | Set | Meridian | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | Thu 7:01 am | Thu 8:05 pm | Thu 1:32 pm | Difficult to see |

| Venus | Fri 4:52 am | Fri 3:54 pm | Fri 10:23 am | Good visibility |

| Mars | Fri 4:37 am | Fri 3:10 pm | Fri 9:54 am | Average visibility |

| Jupiter | Fri 5:48 am | Fri 5:29 pm | Fri 11:38 am | Slightly difficult to see |

| Saturn | Fri 4:29 am | Fri 2:58 pm | Fri 9:44 am | Average visibility |

| Uranus | Thu 7:57 am | Thu 9:41 pm | Thu 2:49 pm | Extremely difficult to see |

| Neptune | Fri 5:50 am | Fri 5:32 pm | Fri 11:41 am | Extremely difficult to see |

April 22-23, 2023: The Lyrids Meteor Shower

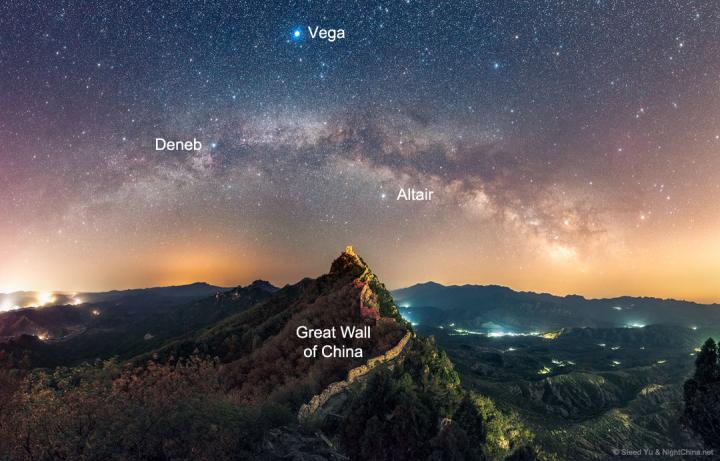

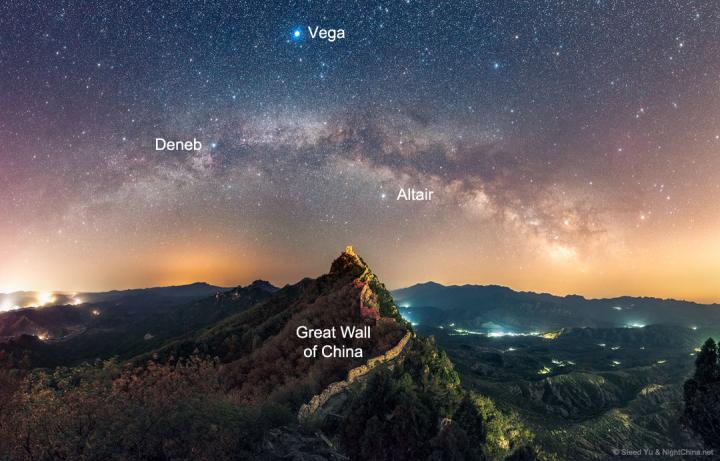

The Lyrid meteor shower – April’s shooting stars – lasts from about April 16 to 25. Lyrid meteors tend to be bright and often leave trails. About 10-20 meteors per hour can be expected at their peak. Plus, the Lyrids are known for uncommon surges that can sometimes bring the rate up to 100 per hour. Those rare outbursts are not easy to predict, but they’re one of the reasons the tantalizing Lyrids are worth checking out around their peak morning. The radiant for this shower is near the bright star Vega in the constellation Lyra (chart here), which rises in the northeast at about 10 p.m. on April evenings. In 2023, the peak morning is April 22, but you might also see meteors before and after that date.

See the following web link for more information:

https://www.timeanddate.com/astronomy/meteor-shower/lyrids.html

Bay Area Bunny (and Hare) Trails

How do you tell a brush rabbit from a Califonia hare (also called California jackrabbit)? Easy. Our common Bay Area rabbit has a powderpuff-like white bunny tail. The hare is much larger and has large, long ears.

You tend to see brush rabbits in dense undergrowth.

Their brown pelage and small size provide camouflage as they rest

under brush and scrub during the day. At dawn and dusk they emerge to

feed on green plants. When threatened, brush rabbits thump their hind

legs against the ground to produce a warning sound. If pursued by a

predator, a rabbit will race away in a zig-zag pattern.

Unlike a brush rabbit, hares can jump up to 20 feet in a single bound, and it can run up to 35 mph when eluding a predator. Baby hares, called

leverets, are born with their eyes open and are ready to run shortly

after birth. In the Bay Area, look for brush rabbits at Sunol Regional Wilderness or in many other spots. Hares are commonly spotted along the Albany waterfront and at Mission Peak, among many other Bay Area locations.

The Sniffling Season

Green hills, golden poppies, and sneezing neighbors are three sure

signs that Spring has arrived in Northern California. While blooming

flowers are obvious visual harbingers that violate our noses, your allergies may be the result of other, more hidden enemies. Before poppies bloom, trees such as alder, ash, oak and juniper initially produce pollen.

On a windy day you can see clouds of golden dust billowing

from these mature trees. Just as trees wind down, a potpourri of grasses and flowers cast their sniffle-inducing spell. Fortunately, for seasonal allergy sufferers, April showers bring temporary relief from suffering, as rain washes pollen out of the air.

Lizards Arising: Western Whiptails

Throughout the state this month, watch for the emergence of reptiles, including Western Whiptails that become active after winter dormancy. At first sighting, don’t mistake the whiptail for a snake, despite their long, 13-inch body that slithers more like a miniature alligator.

As the only common whiptail in the state, you won’t find them easily along the Coast and instead need to explore inland, arid habitats. Here, the juveniles are the initial populations to become active, followed by adult males. The latter compete for females by establishing mating dominance among males that congregate together. Unlike many reptiles that become more difficult to spot as temperatures rise throughout the spring, whiptails remain active throughout much of the day.

Does a whiptail drop its tail as an escape strategy from a predator? Yes, but only in rare cases, and only if it cannot evade the grasp of its pursuer. Growing its tail again takes lots of energy and time, so a whiptail will typically instead bolt from a predator in the blink of an eye to prevent capture.

Butterfly Sightings?

If you’ve recently seen a butterfly species and wish to know if other people have witnessed the same kind or others, then visit a Web site link that is devoted to tracking the appearance of butterfly species throughout North America: http://www.naba.org/sightings/sightings.html

Mountain Beavers: A Family Of One

Have you ever seen a Mountain Beaver? Not many people have been lucky enough to observe these solitary rodents that are in a different family than the more common American Beaver that lives throughout North America. To find a Mountain Beaver, you have to search in moist habitats along the Pacific coast from northern California through Washington and into southern British Columbia, Canada. Little is known about mountain beaver behavior during the breeding season. Breeding activity occurs mainly from January to March with gestation lasting about 30 days. Young are born blind and hairless, weighing about 3/4 ounce (20 g). They develop incisors at about 30 days and are weaned at about 8 weeks. Young animals are often active in May. Females apparently do not bear young until they are two years of age.

As the only member of its family (Aplodontidae) and genus (Aplodontia) in North America, a Mountain Beaver leaves evidence of its presence in the form of packed ground that forms a trail next to its burrow within a forest canopy and/or thick understory. Mountain Beavers are active year-round, but a rare sight, perhaps primarily because their habitat is usually inaccessible and off-trail from where most hikers prefer to explore.

Skinks Underfoot